Background: Early discontinuation of implant contraceptive methods and reasons for discontinuation remains a major concern for family planning programs and is generally higher in developing countries. Discontinuation is closely related to higher rates of the overall fertility rate and unwanted pregnancies, leading to a possibly induced abortion. The proportion and factors associated with early contraceptive implant removal are not well known in Uganda. The study's objective was to determine the magnitude of early implant discontinuation among women receiving implant services in the study area and its associated factors.

Methods: A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from 2nd January to 3rd March 2020 through a face-to-face interview. A total of 207 Implant user women were selected by systematic random sampling technique. SPSS version 20 was used for both data entry and analysis. Factors associated with early Implant discontinuation were analyzed using a binary and multivariable logistic regression model. Variables with a p-value of <0.05 and a 95% confidence interval were considered as statistically significant.

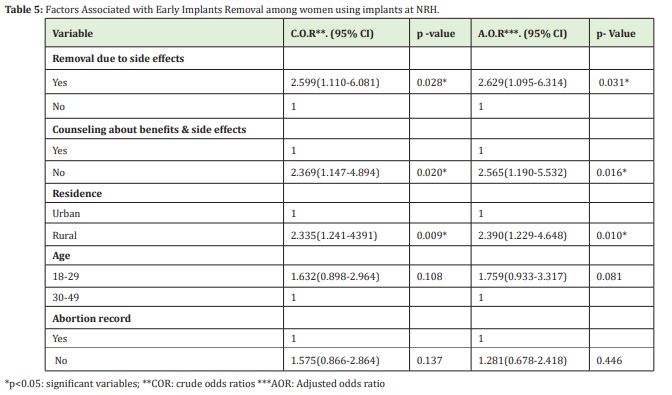

Results: The proportion of early implant discontinuation was 42%. Factors associated with early implant discontinuation included; experience of side effects (OR=2.629; 95%CI:1.095-6.314; P=0.031), not having received pre-insertion counseling about the benefits and side effects of contraceptive implants (OR=2.565; 95%CI: 1.190-5.532; P= 0.016) and staying in rural areas (OR= 2.390; 95%CI: 1.229-4.648; P= 0.010).

Conclusion: Nearly one in every two mothers have early discontinuation of contraceptive implants. Factors associated with early implant removal were side effects, lack of effective counseling before insertion, and staying in rural areas. Hence, health workers should provide adequate counseling services before inserting the Implant, emphasising possible side effects and their immediate management. Spouses, where possible, should be involved during the counselling to increase implant retention. Also, proper screening of women for pregnancy before insertion of an implant should be routine.

Keywords: Early implant removal, Implant, Contraception.

List of Abbreviations: CI: Confidence Interval; IUCD: Intrauterine Contraceptive Device; LARC: Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive; MoH: Ministry of Health; NRH: National Referral Hospital; OR: Odds Ratio; OCP: Oral Contraceptive pills; UBOS: Uganda Bureau of Statistics; UDHS: Uganda Demographic Health Survey

According to the Uganda Demographic Health Survey, 2016, Uganda has a high fertility rate of 5.4, which is the highest in East Africa. The Uganda family planning cost plan, 2014 noted a high number of unplanned pregnancies among rural, poor, and less educated. Also, a higher 32% of sexually active unmarried compared to 28% of currently married women have an unmet need for family planning. The use of implants alone is as low as 6% among married women, and improper use of contraception contributes to high maternal mortality rates of 336/100,000 women.1 The unmet need for contraception among married women worldwide is 10.7%.2 More than 200 million women around the world have an unmet need for contraception.3 Although contraception improves women's life and public health, many clients discontinue contraceptive use because of dissatisfaction related to side effects, contraceptive failure, or other factors.4 This hinders family planning 2020 to have an additional 120 million women and adolescents receiving family planning services by 2020.5

Contraceptive discontinuation is a global problem that is associated with a high number of unplanned pregnancies, and in a year, 182 million pregnancies across the world are unplanned that can be related to improper usage of contraceptives.6 Implants that have been available since 19987 are long-acting progestogen-only reversible contraceptive subdermal rods that act by inhibiting ovulation.8 The method is highly effective, with a failure rate of less than 1% in a year.9 It is easy to insert and remove, though it requires a qualified health care provider.10 Once the women are inserted, they need little user compliance, and there is the rapid return of fertility immediately after removal.8

There are two types of contraceptive implants that include Implanon and Jadelle. Implanon NXT is a single-rod long-acting subdermal hormonal contraceptive for 3-years of use, containing 68mg etonogestrel.11 It is made of ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer with a length of 40mm and a diameter of 2mm.12 Jadelle is a set of two flexible cylindrical implants consisting of dimethyl siloxane/methyl vinyl siloxane copolymer core enclosed in thin-walled silicone tubing.13 Each rod contains 75mg of levonorgestrel and is licensed for use for five years.14,15 After the implant has been inserted, there is no need for frequent visits to family planning clinics though it is associated with changes in the bleeding pattern.7

The main consequence of early removal of implants is unwanted pregnancy that results in unsafe abortion, inadequate antenatal care, adolescent pregnancy, and socioeconomic and health disparities.16 These unintended pregnancies are associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity among women of reproductive age.17

According to secondary data collected from the family planning clinic at Kawempe National Referral Hospital (NRH) showed that almost a third of women who were using contraceptive implants between 22/10/2018 and 6/02/19 opted to discontinue before the recommended period. The reasons for removal before the recommended time were not recorded and are unknown. Currently, Kawempe NRH provides Implanon NXT and Jadelle to women for contraception as Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive (LARC) method of family planning, which is advocated for by the Ministry of Health (MoH). There is a need to understand why women have early removal of contraceptive implants in response to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, especially Goal 3 which ensures healthy lives and promotes well-being for all ages.18 There is limited research in Uganda and Kawempe, in particular, on why women have early implant removal and factors associated with it. The study findings will, therefore enlighten the gaps which can be solved by health workers and stakeholders to improve clients' response to family planning services.

Efforts to increase academic attainment, effective counseling on the side effects at the time of insertion, and women's follow-up will positively impact the continuation of implants.6 Also, public enlightenment on contraceptive efficacy and safety will improve its acceptance among illiterate women.13 Clinicians also should manage bleeding problems by prescribing the combined oral contraceptive pill.15

Study setting

The study was conducted at the family planning clinic, Kawempe NRH in Kampala district. It is found in Kawempe Division in the northwestern corner of Kampala City. Kawempe NRH is located alongside Bwaise- Kawempe road in Kawempe division, 4.2km away from Kampala town. It was established by the government of Uganda to offer Maternal and Child health services to the public. According to secondary data collected from the family planning clinic at Kawempe, NRH showed that 235 out of 625 women who were using implants between 22/10/2018 and 6/02/19 opted to discontinue before the recommended period.

Study Design

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted among women above 18 to 49 years who used contraceptive implants and requested removal at Kawempe National Referral Hospital. Data were collected for almost two months from 2nd -January to 4th -March 2020. Every woman was interviewed on the same day she discontinued the Implant. The date on which she inserted the Implant was recorded from the client card given to her after insertion, which minimized recall bias.

Study Population

All women who requested implant removal at the family planning clinic, Kawempe NRH, were eligible to participate during the study period.

Data collection

Data were collected once from each participant using the quantitative-descriptive method of data collection. Data were collected using face-to-face questionnaires that included open-end and closed-end questions on socio-demographic (age, marital status, religion, occupation, and education), obstetric (number of children, counseling, past contraception utilization), method related (side effects, follow-up, conception, past contraception utilization) and social (pattern opposition and involvement, peer influence) factors.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was determined by using the desired precision e=0.05 for the prevalence of early discontinuation at Kawempe NRH, a confidence level of 95%, and z- statistic for the level of confidence Z=1.96. Using an equation developed by Cochran (1963:75) (Glenn, 1992) for calculating the sample size in research studies, a sample size of 207 respondents was used in the study with a 100% response.

Using an equation developed by Cochran (1963:75) (Glenn, 1992), no=Z2pq/e2, where no is the sample size, Z2 is the abscissa of the normal curve that cuts off an area alpha at tails (1-alpha equals the desired confidence level, e.g., 95%), P is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in the population, e is the desired level of precision and q is (1-p). The value for Z is found in statistical tables that contain the area under the normal curve. Therefore, if the estimated prevalence of early implant removal, p= 16%.16-19 The sample size was 207 women.

Sampling procedure

According to data collected for three and a half months, reported 235 women opted to discontinue implants. The study participants were selected using a systematic random sampling method with kth value 2. The first participant who arrived at the health facility was selected to be the first, and the other third-person was included in the study.

Inclusion Criteria

- The study was composed of women 18 years and above who had come to discontinued implants at family planning clinic, Kawempe NRH, during the study period.

- For a respondent to be included in the study, they must have been a visible record of the date of insertion of the contraceptive implant, either as a client card.

Data Collection Instruments and definition of variables

Data were collected using a semi-structured face-to-face questionnaire having three parts. The first part contained the socio-demographic characteristics of a woman. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of obstetric characteristics of a woman, while the third part consisted of method-related characteristics.

Dependent variable: Early implant removal was the dependent variable, defined as discontinuation at 18 months or less after implant insertion.20 It was measured as a binary variable coded as 'Yes' if an implant was discontinued before 18 months from the time of insertion and 'No' if 18 or more months. Independent variables; these included; socio-demographic factors (age, marital status, religion, occupation, and education), obstetric factors (number of children and number of induced abortion), social factors (husband perception and peer group influence) and method related factors (type and duration of usage, side effects, follow up, conception, counseling, past contraception utilization).

Data Collection Procedure

Participants were recruited at the family planning clinic, Kawempe NRH, every Monday to Friday, between 8.00am and 4.00pm. Data were collected from 2nd January to 4th March using a face-to-face questionnaire. Questionnaires were given to eligible participants after systematic sampling taking the first and the third person in the line among women who came for removal of implants.

One research assistant was trained for one day before data collection on the contents of the study, contents of the questionnaires, and interview skills. The research assistant was a midwife and a staff at the study site.

Data Management

The filled questionnaires' raw data were entered into Statistical Package for Social Services (SPSS), cleaned, coded, and analyzed. The main author was the only person to access files that were protected using a personalized password. Raw data was kept safely in my room, where nobody else could access it without my permission.

Quality assurance was accomplished through data checking that involves; double-checking the coding of the responses, checking data completeness, statistical analyses to detect errors, and abnormal values.

The transformation was performed on variables such as age, marital status, religion, level of education, occupation of the woman, and spouse.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, including proportion, percentage, mean, median, and standard deviation, were presented in text and tables. Results of Bivariate and multivariate analysis are presented in tables. For inclusion into a multivariate model, only variables with a p-value of 0.20 or less after bivariate analysis were considered while establishing determinants of early discontinuation of implants. Multivariate analysis was performed to control for confounders, and the variables were jointly analyzed to attain adjusted odds ratios. The significance level was set at 5% for all tests of significance.

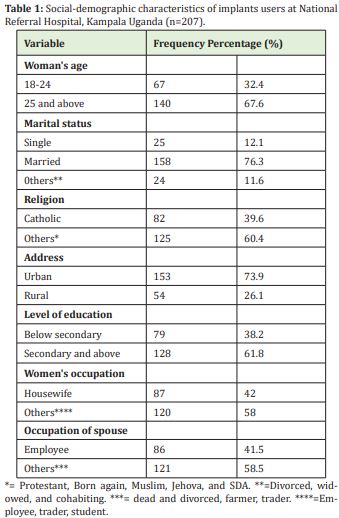

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. Most participants 140/207 (67.6%) were aged 25 years, and above, 128/207 (61.8%) had attained secondary level or above, 158/207 (76.3%) were married, 82/207 (39.6%) were Catholics, while 153/207 (73.9%) stayed in an urban area. The participants were also asked about occupation majority, 87 (42.0%) were housewives, 60 (29.0%) were employed, 56(27.1%) were traders, and majority of their spouses 92 (44.5%) were traders Table 1.

Obstetrics related characteristics

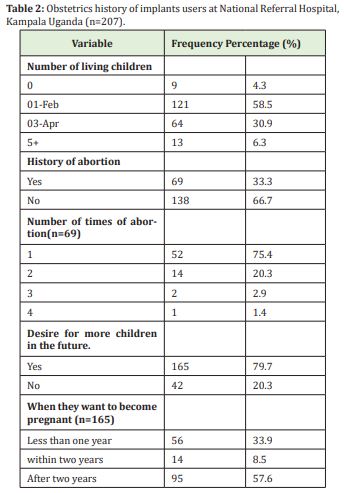

The majority of participants, 121/207 (58.5%) had at least 1-2 children while 13/207 (6.3%) had more than five alive children. Participants were also asked if they had ever had an abortion, 69/207 (33.3%) had ever had an abortion, but most had ever had it once, 52/69 (75.4%). One hundred sixty-five (79.7%) had a desire for more children in the future; out of those who had a future desire to have children, 95/165 (57.6%) wanted to have babies after two years while 56/165 (33.9%) wanted to have babies in less than one year Table 2.

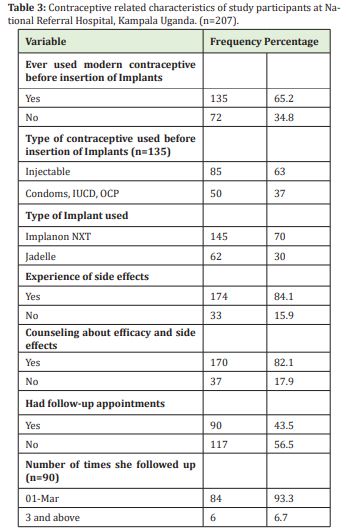

The majority of the participants, 135/207 (65.2%), had ever used modern contraceptives before the currently discontinued Implant; out of those who had used modern contraceptives before 85/135 (63.0%) were using injectable followed by oral contraceptive pills 20/135 (14.8%). Most participants, 145/207 (70.0%) were using Implanon NXT while 62/207 (30.0%) were using Jadelle. All the participants were asked whether they received counseling about the implants in terms of efficacy and side effects, whereby 170/207 (82.1%) reported that they were counseled. Then further asked whether after insertion of implants, they were given future appointment dates, 117/207 (56.5%) of the study participants did not have appointments follow-up during their implant utilization period. Of those 90/207 who had received appointments, 84/90 (93.3%) had 1-3 times appointment dates for follow-up during their implant utilization period Table 3.

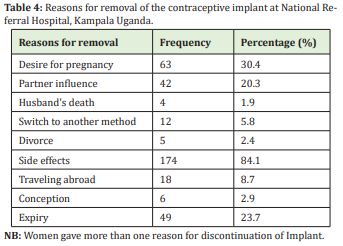

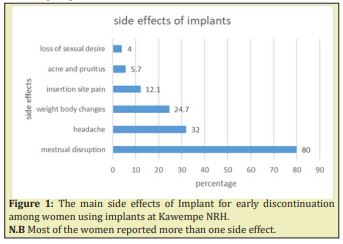

The major reason for early removal of implants was due to side effects that accounted for 174/207 (84.1%) that included 139/174 (80%) for menstrual disruption, 56/174 (32.2%) for headache; weight body changes 43/207 (24.7%), insertion site pain 21/174 (12.1%), acne and pruritus 9/174 (5.7%), and loss of sexual desire 7/174 (4%). Figure 1. These were followed by 63/207 (30.4%) those participants who had the plan to conceive shortly, their partners had influenced 42/207 (20.3%) to discontinue, 6/207 (2.9%) claimed that they had conceived while using Implant, but one participant was interviewed and was found to be pregnant before implant insertion Table 4.

Factors associated with Early Implants Removal among women using implants at NRH

The early discontinuation rate of implants was (42% with a mean of 16.44 months (S.D.) (±12.54) for Implanon, 22.02 months (S.D.) (±17.23) for Jadelle, and 18.11 months (S.D.) (±14.33) for both implants using a cut-off of 18 months. Table 5 shows the factors associated with early contraceptive implant discontinuation. No variable was excluded from the analysis for the association because each category had desired frequencies when checked by cross-tabulation. Each variable was checked individually for the presence of association in binary logistic regression and experience of side effects, not being counselled about the efficacy and possible side effects, and staying in rural areas were significantly associated with early implant removal. Even at multivariate analysis, those three variables mentioned above remained significantly associated with early implant removal.

The result showed that the odds of early discontinuation in those who experienced side effects were 2.6 times higher than for those who reported no side effects (OR=2.629; 95%CI: 1.095-6.314; P=0.031) compared to those who had not experienced side effects. Also, the odds of discontinuation in women who were not counseled on efficacy and possible side effects 2.6 times higher (OR=2.565; 95%CI: 1.190-5.532; P= 0.016) compared to those who had received pre-insertion counseling. Women who stayed in rural areas were 2.3 times more likely to discontinue early contraception (OR=2.390; 95%CI: 1.229-4.648; P=0.010) compared to those who stayed in urban areas Table 5.

The study established the factors associated with early implant removal among women at a National Referral Hospital among 18-49 years who had requested implant removal during the study period. The proportion of early implant removal was relatively high, and factors associated with it were the experience of side effects, lack of effective counseling before insertion, and staying in rural areas.

The proportion of early discontinuation of implants

This facility-based study assessed for early discontinuation of implants (Implanon and Jadelle) among women who were using implants at Kawempe NRH, Kampala district. The prevalence of early discontinuation of implants in this study is similar to that of a study done in Sudan which found a discontinuation rate of 43%.21,22 However, the current proportion is higher than other studies conducted in Ethiopia, 16%19 and 23.4%.8 Other studies done in Ethiopia had a discontinuation rate higher than the current study. In a survey conducted in Debre Tabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia, early discontinuation was at 65%.6 The difference could be attributed to the improved effort of pre-insertion counseling, particularly about the possible side effects of the method as compared to the previous study. In the previous study in Debre Tabor Town, 31.8% were counseled about the possible side effects compared to the current study were 82.1% were counseled.6 Also, more than half in the current study had ever used any other modern contraceptive method before; this increases the chance of a continuation of implants since participants might have familiarized themselves with the side effects of contraceptive methods.21

Different studies show variations in discontinuation rates. This could be attributed to different cut off for early discontinuation whereby in Ethiopia, 2.5 years was used as cut off for early implant removal.6 In contrast, a cut of 18 months was used in Uganda.20 In other studies, the low discontinuation rates were attributed to effective pre-insertion counselling about possible side effects. For instance, in a study conducted in Mekelle City, 34 percent of the women who were counselled discontinued early, while in the current study, 38.2 percent discontinued early of the women who were counselled.22 In Uganda, a study that assessed early discontinuation of both contraceptive implants with an early discontinuation rate was 31% in the facility-based cross-sectional study conducted in the Wakiso District. This was lower compared to the current study, and the difference could be attributed to the denominator for assessing the proportion whereby the current study only included age of 18 years and above while the study done in Wakiso district included women of reproductive age 15-49 years from 42 health facilities in a rural and urban setting.20 The other reason for the difference could be attributed to a cost incurred to retain the Implant where 27.2% of women incurred a cost in the previous study conducted in Wakiso district compared to the current study where services rendered to women were for free of charge; this would be a barrier from seeking health care whenever they experience side effects.

Pre-insertion counselling in family planning helps women and their partners to gain increased control over their reproductive health. Providing counseling during the insertion of Implants was positively associated with the continuation of use.8 Preplacement counseling about the possible side effects of the method and support by the service providers might be the most important way to help women continue on Implants contraception.23 Women and couples who receive better counseling on their method may be more aware of potential side effects and how to cope with them. In this study, the women who were not counselled were more likely to have early implant removal. This is consistent with the study findings conducted in Debre Tabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia.6 This is because when the women are informed about the possible side effect of the method, they will tolerate side effects, but those who were not informed will seek the removal of the method. Timely follow up, and appropriate counseling helps the women to cope with side effects, which ultimately prevents discontinuation. The acceptance and awareness of any contraceptive implants will be increased by involving the couple during counseling sessions.24

The occurrence of side effects has a negative impact on whether a woman continues to use family planning. In this study, women who experienced side effects were more likely to have early implant removal. This is consistent with the study conducted in Tigray,19 and Debre Tabor Town6 where women who experienced a side effect of the method led to early Implant discontinuation. In addition to this, respondents may fear different complication as a result of side effects; this may lead to discontinuation of Implant early. The main reasons for removing the Implant in this current study were side effects, followed by a desire for more children, expiry, partner influence, and conception. Among the side effects, menstrual disruption and headaches were most common. This is consistent with other studies conducted in Ethiopia.19 Menstrual disruption has no serious effects on health but can interfere with daily activities, especially sexual relationships and possibly with work.19 Women who requested implant removal due to side effects would have received misleading information from non-professional persons in the community, lacked appropriate counseling about side effects and appointment dates for follow-up. This means that immediate action upon the management of bleeding problems will enable the continuation of the contraceptive implant.

One of the reasons for early implant removal was pressure from spouses. Men need to understand their role in reproduction to share the responsibility for family planning and birth spacing. In this study, partner disapproval of the contraceptive implant was among the reasons for the discontinuation and accounted for a fifth of early implant removal. Male involvement in maternal health contributes a lot to the reduction of mortality and improvement of maternal health as well as family health.9 This suggests that to enable the continuation of implants, males should be involved in counseling sessions concerning contraception before and during implant use.

Residence appeared to be one factor associated with the early removal of implants. Women in urban areas may be of better socioeconomic status, easy access to family planning services, cultural disparity, and a high level of female literacy compared to women in rural areas. This study showed that women who live in urban areas were less likely to discontinue implants early compared to those who live in rural areas. The difference can be attributed to occupation status. It is possible that women who live in rural areas are housewives and may discontinue implants early to have more children compared to their counterparts in urban areas who work in different jobs. This is in line with a study conducted in Dale District, Southern Ethiopia where women with high monthly income were less likely to discontinue the method.8 Also, some women in urban areas might be sex workers who do not want to get pregnant, thus prolonging the utilization of implants. Women in urban areas might have attained a higher level of education who often seek early healthcare whenever there is any disturbance from normal physiology.25 This increased number of encounter with health workers promotes confidence among women. Also, women who have attained a higher level of education can get more information from different reliable sources about contraceptive implants.22

Being a cross-sectional study that was conducted from a health facility, it was not easy to determine the impact of early discontinuation of implants. Though the data collector was a midwife and well trained before data collection, she was a staff at that health facility, so the interview's bias would not be excluded from this study.

In this study, discontinuation of implants was high as nearly one of every two women had early removal of the Implant. Experience of side effects, counseling services, and staying in rural areas were associated with early discontinuation. Quality family planning services that involve males during counseling sessions on the benefits and side effects are a vital way through which early implant discontinuation can be minimized.

Ethics approval and consent to participants

The study sought approval and abided by the rules and regulations of the institutional review board of Makerere University School of Health Sciences, SHSREC REF NO: 2019-071. Permission to conduct the study was also sought from Executive Director Kawempe NRH. The participants were requested to participate in the study voluntarily following signing the consent form. The purpose and benefits were clearly explained to participants, ensuring privacy and confidentiality.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Special thanks go to participants and staff at the family planning clinic to support the knowledge and time you rendered to me. The author's gratitude goes to colleagues, data collectors, study participants, and friends, indeed Namayengo Rebecca, Derrick Amooti Lusota, Nantuwa Agnes, who have supported me in the process of report development.

I appreciate the financial support provided by the 'Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of State's Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy (S/GAC), and President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) under Award Number 1R25TW011213. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.'

Authors' contributions

G.S., KKD, SNM, Conceptualized, and designed the study, developed the methodology, supervised the data collection, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

- 1. UBOS, ICF. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. In: UBOS, editor. Rockville, Maryland, USA, 2017.

- 2. Bahamondes L, Brache V, Meirik O, et al. A 3-year multicentre randomized controlled trial of etonogestrel-and levonorgestrel-releasing contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2527–2538.

- 3. Callahan RL, Brunie A, Mackenzie AC, et al. Potential user interest in new long-acting contraceptives: Results from a mixed methods study in Burkina Faso and Uganda. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0217333.

- 4. Sanders NJ, Jenny AH, Daniel EA, et al. The impact of sexual satisfaction, functioning, and perceived contraceptive effects on IUD and Implant Continuation at ! year. Women's Health Issues. 2018:401–407.

- 5. Barden-O'Fallon J, Ilene SS, Lisa MC, et al. Women's contraceptive discontinuation and switching behavior in urban Senegal, 2010-2015. BMC Women's Health. 2018;18:35.

- 6. Mengstu MA, Tewodros S, Nigussie, et al. Early implanon discontinuation and associated factors among implanon user women in Debre Tabor Town, public health facilities, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016. International Journal of reproductive Medicine. 2018;3597487.

- 7. Khungelwa PM, Daniel TG, Eyitayo OO, et al. Reasons for Discountinuation of Implanon among Users in Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality, South Africa: A Cross-Sectional study. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2018;22(1):113–119.

- 8. Nageso A, Achamyelesh G. Discontinuation rate of implanon and its associated factors among wome who ever used implanon in Dale District, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Women's Health. 2018;18(1):189.

- 9. Adeagbo AO, Mullick S, Pillay D, et al. Uptake and early removals of implanon NXT in South Africa: Perceptions and attitudes of healthcare workers. SAMJ. 2017;107(10):822–826.

- 10. Babatude AG. Attempted self-removal of implanon: A case report. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction. 2015;4(3):247–248.

- 11. Park J, Ung, Hans S, et al. Removal of a subdermal contraceptive implant (implanon NXT) that migrated to the axilla by C-arm guidance. Medicine. 2017;96(48):e8627.

- 12. Sapna S, Suman G, Nitu N, et al. A study of efficacy and safety profile with sub dermal single rod contraceptive implant. Journal of Evolution of Med and Dent Sci. 2015;4:3765–3773.

- 13. Muhammad Z, Ibrahim S, Attah R. Jadelle subdermal contraceptive implant in aminu kano teaching hospital kano, northern nigeria. Trop J obstet Gynaecology. 2016.

- 14. Ornu EO, Ojule Dj. A Decade of Jadelle Subdermal Implant Contraception in a Tertiary Health Institution in Port Harcourt, Southern Nigeria. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines. 2018:123–30.

- 15. Roke C, Helen R, Anna W. New Zealand women's experience during their first year of Jadelle contraceptive implant. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2016;8(1):13–19.

- 16. Bahamondes L, Brache V, Olav M, et al. A 3-year multicentre randomised controlled trial of etonogestrel-and levonorgestrel contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Human Reproduction. 2015;30(11):2527–2538.

- 17. Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Byamugisha J, et al. Persistent high fertility in Uganda: young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of contraceptives. BMC Public Health. 2010;10.

- 18. Dockalova B, katie L, Heather B, et al. Sustainable Development Goals and Family Planning 2020. IPPF. 2016.

- 19. Birhane K, Hagos S, Fantahun M. Early discontinuation of implanon and its associated factors among women who ever used implanon in Ofla District, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Pharma Sciences and Research. 2015;6(3):544–551.

- 20. Ddungu U. Factors Asssociated with Early Discontinuation of Contraceptive Implants among Women of Reproductive Age in Wakiso District, A Facility Based Cross-Sectional Study. Dspacemakacug. 2019.

- 21. Susan W Maina, George O Osanjo, Stanley N Ndwigah, et al. Determinants of Discontinuation of Contraceptive Methods among Women at Kenyatta National Hospital, Kenya. African Journal of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2016;5(1).

- 22. Tsirity GM, Kahsu G, Gebrekidan, et al. Early implanon discontinuation rate and its associated factors in health institutions of Mekelle City, Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12:8.

- 23. Romano ME, Braun-Courville DK. Assessing Weight Status in Adolescent and Young Adult Users of the Etonogestrel Contraceptive Implant. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32(4):409–414.

- 24. El-Khoury M, Rebecca T, Minki C, et al. Counseling Women and Couples on Family planning: A Randomized Study in Jordan. Studies in Family Planning. 2016.47(3):222–238.

- 25. Melese S, Desta, Kassa M. Premature Implanon Discontinuation and Associated Factors Among Implanon User Women in Ambo town, Central Ethiopia, 2018. Journal of health Medicine and Nursing. 2018;58:39–46.