The older persons with dementia will occupy more hospital beds in the years to come. Caring for a patient living with dementia is challenging for the hospital staff, especially for those exhibiting neuropsychiatric symptoms. Providing person centred care has been recognised as the ideal model of care for the persons with dementia. However, this care model is time consuming and requires training and education. Provision of good care in the hospital for the older persons with dementia include avoidance of restraints, prescription of psychotropics, in-hospital fall reduction, minimising risk of cognitive and functional decline with discharge home to their families and loved ones.Person centred care is effective in the acute setting,with proper training, guidance and leadership.

Keywords

Dementia, Falls, Restraints, Person-centred care, Neuropsychiatric symptoms

Dementia represents a significant health and psychosocial problem in the context of an ageing population.1 The prevalence of dementia and cognitive disorder in Singapore is expected to increase rapidly over the years, as we face the silver tsunami. In high income countries about 50% of the elderly living with dementia is not formally diagnosed. This may be due to lack of public awareness, coupled with lack of confidence among the medical professionals in making a diagnosis. Currently, only 20-50% of cases with dementia are documented in the primary care setting.2 Without formal diagnosis of dementia, the elderly miss out on treatment options, referrals to community services, education, support and counselling for their caregivers. As such, the caregivers often experience caregiver stress leading to burn out as they face increasing difficulties, in terms of symptoms management due to declining cognition, physical burden and emergence of behavioural symptoms. The persons with dementia (PWD) also miss out on opportunities to be included in research. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) are of primary concern in dementia care. The NPS are difficult to manage, because caregivers stress and increase the risk of institutionalization. The use of psychotropic drugs to control the NPS is known to have harmful side effects, such as falls, extrapyramidal side effects and sedation. Non Pharmacological interventions should be the first approach in managing the NPS, as these are associated with less harm and are more rewarding for the caregivers.

The NPS of dementia make little sense to the untrained staff working in an acute hospital with high turnover, except that they frequently cause frustrations and interfere with everyone’s busy work schedule, while worrying about the patients’ safety. These symptoms are often challenging for untrained staff, particularly when they have to balance against patients’ safety when the agitated and restless patients are confused and don’t seem to follow instructions consistently.

In busy acute hospitals with rapid turnover, the nursing staff works on a tight schedule where care is delivered in a task-oriented manner, rather than person centred. Task oriented model of care focus mainly on attending to the patients’ physical needs, while neglecting their psycho-social needs until there is imminent danger. In a NHS survey, it was shown that 60% of the persons with dementia (PWD) were not treated with dignity or respect, with >90% of the patients being frightened by the hospital environment. This finding is not surprising since only 2% of the NHS staff received formal training in mental health.3 In an acute hospital setting, the elderly with dementia are more likely to be restrained due to emergence of challenging behaviour, coupled with nurses who have no formal training in geriatric care and hence have little idea how to cope with the behavioural symptoms.4

The Dementia ward in Changi General Hospital (CGH), which opened in 2015, is a new service in the teaching hospital. The ward is designated to take care of the elderly patients with delirium/dementia exhibiting difficult to manage behavioural symptoms like aggression, agitation, restlessness, wandering, resisting care, etc. The patients in the ward were taking over from the other wards where the patients’ behavioural symptoms were not manageable. The nurses in the general wards are likely to physically restrain the agitated and restless PWD for fear of falling in the wards. Falls in the hospitals are generally considered as sentinel events which may result in injuries, litigation, feelings of guilt, etc. The usage of physical restraints enforces immobility with a hope to reduce inpatient falls. Unfortunately, physical restraints have not been convincingly shown to reduce falls.5 On the contrary, restraint usage has been well known to be associated with injurious falls and complications like asphyxiation, fractures, delirium, depression, worsening cognitive symptoms and could also cause complications due to immobility like urinary retention, pressure sores, functional decline, pneumonia, constipation, etc.6 The use of restraints on these older patients with dementia should be reserved as the last resort when all else failed.

Person centred care (PCC) is a holistic approach aimed to maintain the well-being of PWD which includes focusing on the person’s uniqueness and preferences instead of the disease and its symptoms.The PCC approach enables health care providers to understand and attend to the unmet needs of the individuals with dementia.7,8 PCC encourage the health care staff to understand the PWD’s current cognitive abilities, life experiences and form a genuine and trusting relationship with the PWD under their care to uphold personhood for the PWD. Provision of PCC also include providing a positive social environment where the staff are trained to treat the PWD with dignity and respect the PWD as an unique individual9 while providing a physical environment which is homelike to reduce disorientation. In institution settings, PCC has been shown to improve PWD’s well-being, reduce emergence of behavioural symptoms, antipsychotic use and improvement of staff’s job satisfaction and retention.10-12 PCC is traditionally practised in long term care setting, with little experience in an acute hospital setting. It is not a new model of care in the care of the elderly wards in the author’s hospital. However, PCC is not consistently practised since this model of care requires commitment and higher staffing to patient ratio.

The environment in the dementia ward is home like, with long corridors adorned with wall pictures to encourage mobility, park benches for intermittent rest in between, etc. PCC in the dementia ward also focuses on designing meaningful activities, tailored for the individual’s interests and cognitive abilities. The therapies include music therapy, robotic pets, multisensory stimulation therapy, art and craft, reminiscence therapy, doll therapy, etc. The staffs was trained on understanding the nature of the behavioural symptoms, and creating non pharmacological means for management of behavioural symptoms, which takes much more time and effort rather than simply restraining or sedating the patients with chemical restraints.

For each patient admitted to dementia ward, the medical and nursing team gather information from the family and caregivers with regards to patients’ likes, dislikes, premorbid personality, coping mechanism, spirituality, daily routines, previous occupations, hobbies and medical problems which may cause discomfort and pain. Analysis of the causes of cognitive impairment help the team understands the nature of their cognitive impairment. Individualised care plans to allow for freedom of movement, food choices, maintaining their usual daily routine while they receive treatment in a safe, secure and home like environment. The staff is trained to handle the PWD with respect, sensitivity and dignity.

The activities are individualised and planned in advance, led by nurses or therapists and sometimes facilitated by volunteers. The model of care means facilitating and assisting patients with their ADLs. The staffs are discouraged from taking over these activities, if the PWD are still capable of performing them. Instead, they are assisted, enabled and facilitated to complete the tasks. Meals are preferentially served in the communal dining areas unless contraindicated, to encourage social interactions. The ward has retro music playing softly in the background for most of the day. The ward has an in-house dietician who is actively engaged to provide individualized meal plans to meet the individual patient’s nutritional requirements.

This is a descriptive study, with retrospective data collection for the patient outcome in the dementia ward since it opened in 2015.

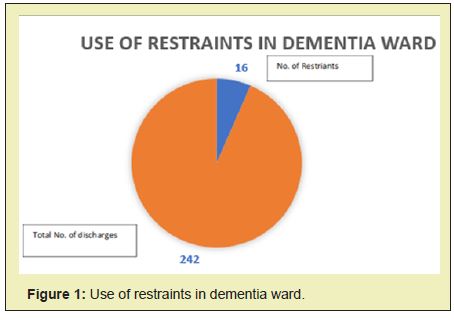

The data over the period of 1 year from January 2018 to December 2019 was reviewed, with total number of 1886 admissions to dementia ward. There were only 3 falls noted during the year. The ward recorded an average of 0.5 falls per month at baseline. The mean length of stay was 12 days.The use of restraints account for 6.6% (n=16) of total admissions between December 2018 and March 2019. (Figure1)

About 80% of the patients were successfully discharged to their own homes, 11.17% of patients were transferred to sub-acute ward for optimization of geriatric care and rehabilitation. For the patients (3.7 %) who needed slow stream rehabilitation of up to 4 weeks’ duration, they were transferred to the community hospital, while only 3 patients (1.5%) out of the total (4.2%) were discharged to nursing homes as new residents. The feedback from the patients’ family were collected and analysed. The response rate was 98.7% from all the discharges in the study period. It is a routine practice of the hospital where the patients or their relatives are encouraged to fill in an anonymous survey form prior to leaving the hospital. The overall patient’s satisfaction rate was 94.2%, with relatives stating that they would strongly recommend the dementia ward for their loved ones’ stay in a hospital. The level of commendation was the highest amongst all the wards in the hospital.Dementia ward nurses’ and doctors’ communication with the patients’ relatives and caregivers were given the top ranking by over 97% of the patients’ relatives. The ward’s allied health professionals’ communication with the patients’ families was also the top among all the hospital wards at 96%.

On food feedback, 91.4% were satisfied with regards to the meal taste, 95% commended that the food was served at the right temperature, in comparison to all the general wards which scored 33% and 43.5 % respectively.

Person centred care (PCC) focuses on treating everyone with deep respect, humanity, dignity in a morally ethical way. The provision of good dementia care focuses on fostering a genuine and warm relationship between the persons with dementia (PWD) and their caregivers. To implement PCC as the model of care, the person is placed in the centre of his/her own care where the person is supported, enabled and facilitated in shared decision making and in their care. The focus of care is to provide a positive environment where personhood is upheld in order to provide and maintain a state of well-being. In the world of the PWD where their world is confusing and ever changing, the care plan is individualised based on their routines and activities are created according to the individual’s previous occupation, hobbies and taking into considerations their current cognitive abilities.6,13 Person centred care has been shown by multiple researches to be beneficial in reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia like agitation and depression14 with dementia improvement in their quality of life.8,14,15 PCC also reduces cost of care.10 There are unfortunately few randomized controlled trials on PCC. In PCC, the caregivers are taught to look at the world from the PWD’s perspectives, and the emergence of neuropsychiatric symptoms interpreted is due to miscommunication between the caregivers and the PWD resulting in unmet needs. PCC has shown positive outcome in long term care setting.16

There is widespread usage of physical restraints among elderly with dementia in acute hospitals. In United states, the usage of physical restraints is about 17% (11) in the acute settings, 25.5% in Japanese long stay wards17 and can be as high as 44.5% in acute care hospitals in Japan.13 Restraints are mostly applied for patients’ safety, fall reduction, refraining from removal of medical equipment such as IV lines, indwelling catheters, tracheostomy tubes, feeding tubes, etc. A study conducted in Singapore General Hospital, among the elderly patients aged >65 admitted from February 2012 to August 2012 showed use of physical restraints among 8% of patients, and the major reasons for restraints included challenging behaviour/confused/violent in 65% of the cases and attempts to prevent falls quoted by 62%. The strongest predictor for restraint was memory disturbances.

In the dementia ward, the person-centred approach of care for people with dementia appears to be associated with minimal usage of restraints (6.6%) and yet, there were only 3 falls for the whole year which is lower than the other inpatient wards in the hospital. A study in psychogeriatric ward in Hong Kong showed that the 66% inpatient falls was among the older patients with dementia.18 In the US Psychiatric Care, the national database of Nursing Quality Indicators from April 2013–March 2019 on falls among patients of adult and geriatric psychiatric units of general, acute care, and psychiatric inpatient units were examined. The sample included 1,159 units in 720 hospitals. There were 119,246 falls reported. Among these, 25,807 (21.6%) inpatient falls resulted in injury. The total fall rate (8.55 per 1,000 patient-days) and injurious fall rate (1.97 per 1,000 patient-days) were highest for geriatric psychiatric units, compared to the other disciplines in general hospitals.19

In a retrospective study conducted in Singapore General Hospital, 298 patients>65 years fell during their hospital stay, the majority of fallers (n=248) did not have documented diagnosis of dementia. Fallers with dementia were more likely to be confused at the time of the fall. Their study also found the main risk factors for falls, was patients nursed with restraints.20

The patients in the dementia ward are encouraged to mobilise with supervision in order to reduce risks of functional decline. The low fall rate, coupled with minimal usage of restraints for this group of patients with challenging neuropsychiatric symptoms was achieved through diligent handover of care, early assessment of fall risk and multidisciplinary interventions for fall risk reduction. The measures in place for reducing falls included medication review, screening for postural hypotension with early intervention, early referrals to the allied health professionals for mobility and assessment of function.21 The patients’ families and caregivers are routinely given individualised education and counselling sessions based on their individualised needs, focusing on management of neuropsychiatric symptoms. The allied healthcare professionals educate the caregivers on creating therapies and find ways to engage the PWD with meaningful activities, in order to reduce psychotropic medication for management of neuropsychiatric symptoms. As a result, 80% of the patients were successfully discharged back to the patients’ own home.

The patients in the dementia ward have their meals from the hospital’s kitchen, just like every other ward in the hospital. However, the nursing staffs take the trouble to ask the patients or their family their preferred choices for their meals. Since the hospital food tends to be on the healthy side, the staffs take the trouble to season the food prior to serving the patients their meals. The staff also took the trouble to ask the patients’ caregivers and families on the patients’ preferences on food and drinks in order to encourage oral intake and minimise weight loss during the recovery from their medical or surgical illnesses. The elderly generally lose weight during stay in the hospitals, resulting in functional decline, increased cost, poor wound healing and delirium.22 Assessment of nutrition is often neglected by the medical professionals and it is well known that the PWD develop eating and swallowing disorders with progression of dementia.23 In order to maintain and encourage oral intake, the dementia ward engage a multidisciplinary approach involving the nursing staff, dietician, speech therapists and occupational therapists to assess the problems causing poor oral intake for the PWD. Meal times are in the communal dining areas, unless the patients are not fit to be seated out of bed. There are trained staffs around during meal times to assist with feeding. The patients’ meals are individualised according to their nutritional and caloric requirement and the patients’ weight and intake charting are reviewed on a regular basis to prevent weight loss.

Part of PCC involves providing a positive social environment to maintain a state of well-being. The positive social environment involves training our staff to treat and handle the PWD with dignity with positive enhancers and strict avoidance of personal detractors as practiced by dementia care mapping (DCM).The staffs have regular education on practice of PCC, especially the code of conduct identified under personal detractors in order to uphold personhood. A positive nurses’ attitude has influenced the success of reduction of use of restraints and falls. Incorporating multidisciplinary strategies and supporting PCC, like management of patients’ nutritional requirements, cognitive and sensory stimulation activities, providing a home-like ward environment was the key to provide good dementia care in a hospital environment.

The practice of PCC is not well researched in an acute hospital setting. The practice of PCC is traditionally considered as the best care model in the long-term institutional care setting where the staff has more time to get to know the PWD under their care and modify care plans according to the PWD’s likes and dislikes. Nevertheless, it is shown that PCC is not impossible in an acute hospital setting, with good outcomes like reduction of restraint use, fall reduction, high caregiver satisfaction and early discharge home.23-26

The team would like to acknowledge the commitment, team spirit and perseverance of the ward 58 staff, Changi General Hospital who are the key for a successful patient outcome.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Parkin E, Baker C, Dementia: policy, services and statistics. House of Commons Library; 2018.

- 2. Dementia statistics | Alzheimer’s disease International (ADI).

- 3. Philip D Sloane, Beverly Hoeffer, C Madeline Mitchell. Effect of Person- Centered Showering and the Towel Bath on Bathing-Associated Aggression, Agitation, and Discomfort in Nursing Home Residents with Dementia: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1795–1804.

- 4. Lim SC, Chiam WM, Goh CH, et al. Initiatives to Improve Awareness of Delirium in a Teaching Hospital in Singapore: for Better Patient Care. 2019;2(3).

- 5. Tang WS, Chow YL, Koh SSL. The effectiveness of physical restraints in reducing falls among adults in acute care hospitals and nursing homes: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(5):307–351.

- 6. Lim SC, Poon WH. Restraint use in the management of elderly with dementia in hospital. Internal Med Res Open J. 2016;1(2):1–4.

- 7. Kitwood T, Bredin K. Towards a theory of dementia care: personhood and well-being. Ageing Soc. 1992;12:269–87.

- 8. Edvardsson D, Fetherstonhaugh D, McAuliffe L, et al. Job satisfaction amongst aged care staff: exploring the influence of person-centered care provision. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(8):1205–1212.

- 9. SC Lim, Peter CL Chow. Managing eating disorders in elderly with dementia and the ethical considerations for tube feeding. Int J of Psych. 2018;3(1).

- 10. Lim Sc, Kaysar Mamun, Jim K H Lim. Comparison between elderly inpatient falls with and without dementia. Singapore Med J. 2014;55(2):67–71.

- 11. Eva Elisabeth Steenbergen, Roos-Marie van der Steen, et al. Perspectives of person-centred care. Nurs Stand. 2013;27(48):35–41.

- 12. Lim Jing Wei, Lin Huimin, Sinnatamby Savithri. Multidisciplinary Falls Risk Interventions help reduce falls in a Dementia Ward.

- 13. Abraraw Lehuluante. Anita Nilsson, David Edvardsson. The influence of a person-centred psychosocial unit climate on satisfaction with care and work. Journal of Nursing Management. 2012;20(3):319–325.

- 14. Esther Heerema MSW. Thomas. Kitwood’s Person Centered Care for Dementia, A Practical Way to Improve Quality of Life. 2020.

- 15. Kim SK, Park M. Effectiveness of person centered care on people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:381–397.

- 16. Junxin Li, Davina Porock. Resident Outcomes of Person-Centered Care in Long-Term Care: A Narrative Review of Interventional Research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(10):1395–1415.

- 17. Felicia Hui En Tay, Claire L Thompson, Chih MingNieh, et al. Personcentered care for older people with dementia in the acute hospital. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2018;4:19–27.

- 18. Wong MMC, Pang PF. Factors associated with falls in psychogeriatric inpatients and comparison of two fall risk assessment tools. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry. 2019;29(1):10–14.

- 19. Kea Turner, Ragnhildur Bjarnadottir, Ara Jo et al. Patient Falls and Injuries in U.S. Psychiatric Care: Incidence and Trends. 2020;71(9):899– 905.

- 20. Clive Ballard, Anne Corbett, Martin Orrell, et al. Impact of person-centred care training and person-centred activities on quality of life, agitation, and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in nursing homes: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2018;15(2): e1002500.

- 21. Si Ching LIM. Nutrition and the Role of Tube Feeding in the Elderly. J J Geronto. 2016;2(1):017.

- 22. Chiba Y, Yamamoto-Mitani N, Kawasaki M. A national survey of the use of physical restraint in long-term care hospitals in Japan. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(9-10):1314–1326.

- 23. Liz Burton. What is Person-Centred Care and Why is it Important? Person-Centred Care: What is it & Why is it Important?

- 24. Miharu Nakanishi, Yasuyuki Okumura, Asao Ogawa. Physical restraint to patients with dementia in acute physical care settings: effect of the financial incentive to acute care hospitals. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(7):991–1000.

- 25. Si Ching LIM. Nutrition and the Role of Tube Feeding in the Elderly. J J Geronto. 2016;2(1):017.

- 26. Alzheimer’s UK, Jurgens FJ et al. Why are family carers of people with dementia dissatisfied with general hospital care? A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12(1):57.