Background: Depressed and anxious patients experience of intense discomfort in the chest. Anguish is a feeling that causes discomfort in the chest that translates into physical sensations or bodily manifestations such as tightness, pain, hole, suffocation or compression in the chest.

Method: Were included in the research 100 patients treated at the general, anxiety and adult affective disorders outpatient clinics of the Institute of Psychiatry of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Result: Diagnosis of depression was selected in the model (at the 10% level) and its interpretation corroborates the central hypothesis of the study. Correspondence analysis also points to clues in the direction of the research hypothesis. As for the second objective, under the same logistic model, the following variables were shown to be related to the state of anguish: Gender, Reduced HAM-A Score, BSI Somatization, BSI Hostility, BSI Obsession-Compulsion, Age and MINI Depression.

Conclusion: The results of this research highlight the need for promoting a more criterious investigation about the role of anguish in mental health.

Keywords: Anguish, Anxiety, Chest pain, Depression, Mental health

Gentil & Gentil1 hypothesized that anguish could have clinical and neurobiological relevance. Over the last few decades, anguish has been confused with fear, panic and anxiety. Anguish, which focuses on presente events, is accompanied by sensations in the thoracic region that can present themselves in the form of pain or tightness and many patients with depression and anxiety report this experience. The word anguish goes back to the Latin verb angere, which means squeezing, compressing (especially the throat), strangling, choking, suffocating.2 In the scientific field, anguish arose when the word angst was inserted by Freud. However, angst was translated into anxiety,3 because was a term which could be translated to “fear”, “fright”, “alarm”. Thus, was concluded that 'anxiety' would also have a common meaning in everyday use, with only a remote connection with any of the uses of 'angst’ and that it would be ‘impractical’ to settle on a single English term as a translation. exclusive, but that there would be a use already established by psychiatry that would justify the choice of the term “anxiety”.4 The first consistent records of this human experience, which today is called anguish or anxiety, are found in the writings of pre-Socratic philosophers. According to Pessotti,5 they were the first to record more rational thoughts about anxiety, without using the word anxiety, obviously. Del Porto (2002,p.4), in turn, states that in Roman Antiquity the philosopher Cicero already divided the field in question into two domains, anguish and anxiety. Anguish was something acute and transitory, while anxiety was a more or less permanent constitutional predisposition. This ancient distinction, despite being formulated in a philosophical context, would have a great influence on the psychopathological field, especially on French psychiatrists at the end of the 19th century. Despite the possibility of making this reference to the ancient world, as well as in relation to the findings of numerous philosophical works on the subject throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it was only at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, when the The concept of anxiety is established in the field of psychopathology, and the distinction between anxiety and anguish gains relevance, especially in the context of French psychiatry.6 Berrios7 as part of a historical review of the concept of anxiety, shows that throughout the 19th century, anxious symptoms were studied in clinical areas such as cardiology, otorhinolaryngology, gastroenterology and neurology, and that, only at the end of the century, in the context of French psychiatry, were they brought together into a specific syndrome related to anxiety. At that time, anguish was conceived as suffocation, chest tightness, tachycardia and tremors; while anxiety was understood as distress, restlessness and indefinite terror. Some authors considered that in addition to clinical importance, this separation had neurophysiological bases, with “anguish being a bulbar phenomenon and anxiety a cerebral phenomenon”.8 Brissaud defended the position that “angst is a brain stem phenomenon (bulbar phenomenon), anxiety is a cortical phenomenon (cerebral phenomenon): anguish is a physical disorder that manifests itself as a feeling of constriction and suffocation; Anxiety is a psychological disorder that manifests itself as a feeling of indefinable insecurity.” Brissaud mentions the clinical case of a patient who would have suffered from anguish without anxiety: “after more than a hundred attacks of severe chest pain, he maintained a philosophical attitude, lived day to day and never developed sadness or panic”.7

Anguish was more visceral and static, and anxiety was more muscular and implied movement”.9 Boven also proposed a gradation of intensity, reserving the term anguish for the most serious conditions. Here we find the familiar dichotomy between mind and body so dear to Western thought. In 1895, Freud published the article “On the criteria for distinguishing a particular syndrome from neurasthenia entitled: anxiety neurosis”.10

The contribution of Freudian psychoanalysis to the problem of anxiety can be divided into two theories: Automatic Anguish and Signal Anguish.11 The theory of Automatic Anguish postulates the automatic transformation of repressed libido into anguish to maintain a minimum, or optimal, level of tension. It is understood that anguish is a mere physiological reaction to excess undischarged nervous excitement. It is an attempt to apply the principle of homeostasis to the nervous system and Fechner's Principle of Constancy to Psychopathology.12 In the second theory, that of Signal Anxiety, it is understood that anguish consists of a signal triggered in situations of danger, functioning as an Ego device for anticipating instinctual emergencies (coming from the Id) through the production of a moderate dose of displeasure that prepares the subject for the task of repression according to the pleasure principle.12 However, if from a nosographic and terminological point of view Freud does not distinguish anguish from anxiety, as he uses the term Angst to refer to both phenomena, Freud does so from a symptomatic point of view. It is possible to clearly see that, in his description of the clinical picture of Angstneurosis, Freud separates anguished expectation (anxiety) from a feeling of anguish. The term Angstneurosis is translated into Portuguese both as “anxiety neurosis and as “anxiety neurosis”, indicating that anxiety and anguish are taken as synonyms, although the term anxiety neurosis is the most used; and when the distinction occurs, anguish is taken as the broader term that includes anxiety symptomatology, that is, Angstneurosis is anxiety neurosis, a condition that brings together both anxious symptomatology and distressing symptoms. Returning to the historical line of psychopathology, the distinction between anguish as a physical, acute, and more paralyzing phenomenon; and anxiety as a psychic, constitutional phenomenon and more restlessness, formulated by French psychiatry at the end of the 19th century, predominated for several decades. But, around 1945, Boutonier arguered that this separation was artificial and almost never observed in the clinic. Boutonier defended the use of only the word anguish, meaning simultaneously the physical and psychic aspect of the phenomenon: “anguish is an affective and organic state”.13 This position is part of the humanist and philosophical tradition that understands anguish as part of the human condition itself, which has had great influence in the field of mental health, especially in psychoanalysis. It was the time of anguish, which consisted of a reference to the first half of the 20th century, a time in which the strong psychoanalytic influence in psychiatry would have been one of the reasons for the popularization of anguish and not anxiety.14,6

Vieira & Neto15 investigated the relation between psychopathological symptoms and the diagnosis of depression and anxiety with the experience of anguish and concluded that anguish is more associated with depression than anxiety, being more frequent in females, and that the most frequent comorbidities among patients with anguish are somatization, fears, depressive mood, gastrointestinal and neurovegetative symptoms.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of The exploratory study involved 100 patients of anxiety and adult affective disorders outpatient clinics of the Institute of Psychiatry of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, with 50 patients belonging to the group with anguish and 50 to the group without anguish.

Participants

The sample was of 100 patients treated in the general, anxiety and adult affective disorders outpatient clinic of the Institute of Psychiatry of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, with 50 patients belonging to the group with anguish and 50 to the group without anguish. The reason for including affective and anxious patients in the sample is related to the objective of the research, to discover whether anguish is a feeling that is more focused on depression or anxiety.

Ethics statement

The investigation was approved by the ethics committee of the Center of Studies and Research of Institute of Psychiatry of the Faculty of Medicine of University of São Paulo. All participants digitally signed an Informed Consent Form.

Instruments

Sociodemographics

Participants answered sociodemographic questions anout age, gender, education level and marital status.

Brief inventory of psychopathological symptoms

This inventory was developped by Derogatis (1982) and adapted for portuguese language by Canavarro16 and evaluates psychopathological symptoms related to nine different dimensions and culminates in a summary evaluation consisting of three Global Indices. The nine dimensions as follows: Somatization: includes items 2, 7, 23, 29, 30, 33 and 37; Obsessions-Compulsions: includes items 5, 15, 26, 27, 32,36; Interpersonal sensitivity: includes items 20, 21, 22 and 42;Depression: includes items 9, 16, 17, 18, 35, 50; Anxiety: includes items 1, 12, 19, 38, 45, 49; Hostility: includes items 6,13, 40, 41 and 46; Phobic Anxiety: includes items 8, 28, 31, 43and 47; Paranoid Ideation: includes items 3, 14, 34, 44 and 53; Psychoticism: includes items 3, 14, 34, 44 and 53. For each BSI subscale, scores were significantly higher than the norms. The nine subscales exhibited acceptable-to-good Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, varying from 0.733 for psychoticism to 0.875 for depression. Overall, the reliability of the entire instrument proved to be excellent (alpha coefficient=0.972). Furthermore, all BSI subscales as well as BSI synthetic indexes correlated with nomophobia in a significant way. Stratifying the population according to the severity of nomophobia (mild, 206 individuals, 51.1% of the sample; moderate, 167 subjects, 41.4%; and severe, 30 individuals, 7.4%), the GSI score could distinguish (P<0.001) between mild and moderate (0.99±0.71 vs 1.32±0.81) and between mild and severe (0.99±0.71 vs 1.54±0.79) nomophobia, although not between moderate and severe nomophobia (P>0.05). Similar patterns could be found for the other subscales of the BSI. Finally, looking at the fit indexes, the second-order 9-factor model best fit the data compared with the Derogatis 1-factor model.

Defense styles inventory

Ego defense mechanisms, which is a psychoanalytic concept, have been defined as an indication of how individuals deal with conflict.17 The defensive style is considered an important dimension of the personality structure of the individual and became the first psychoanalytic concept recognized by the DSM-IV13 as a guide for future research.18 As for the psychometric properties of the DSQ-40, the internal consistency of the mature, neurotic, and immature defense styles was 0.70, 0.61, and 0.83, respectively. Additionally, the 3 defense styles had acceptable split-half reliability and test- retest reliability coefficients. Considering the concurrent validity, the mature defense style was negatively correlated with the symptoms of depression and anxiety, whereas the immature defense style was positively correlated with these symptoms. The neurotic defense style, on the other hand, had a positive correlation with anxiety symptoms, but did not reveal a significant correlation with depressive symptoms. The examination of criterion validity revealed results were consistent with our expectations. Significant differences were found in the expected direction between the control and clinical groups.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is divided into two subscales: the anxiety subscale (tension or contraction, fear, worry, difficulty relaxing, butterflies or tightness in the stomach, restlessness, panic) – HADS-A and the depression subscale (anhedonia, difficulty finding humor when seeing funny things, deep sadness, slowness in thinking and performing tasks, loss of interest in taking care of one's appearance, hopelessness, lack of pleasure when watching television programs, radio or reading something) – HADS- D. Both contain seven items interspersed between questions regarding anxiety and depression. The factors and their corresponding items are shown below: Anxiety symptoms: items: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13. Depression symptoms: items: 2, 4, 6,8, 10, 12, 14 All items are classified on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3. Through these defined values, the HADS subscales can indicate the presence of anxiety or depression disorders at different levels: 0-7, normal; 8-10, light; 11-14, moderate; 15- 21, serious. This scale, after studies and validation for the Brazilian population and the Portuguese language, has been widely used. The questionnaire is self-administered, and the evaluated subject can count on the help of the evaluator, who in the case of this work was always the same, if he did not understand the content of some questions. Twelve studies assessed the psychometric properties of the HADS-Total and its subscales HADS-Anxiety and HADS-Depression. High-quality evidence supported the structural and criterion validity of the HADS-A, the internal consistency of the HADS- T, HADS-A, and HADS-D with Cronbach's alpha values of 0.73-0.87, and before-after treatment responsiveness of HADS- T and its subscales (minimal clinically important difference = 1.4-2; effect size = 0.45-1.40). Moderate-quality evidence supported the test-retest reliability of the HADS-A and HADS- D with excellent coefficient values of 0.86-0.90.

Hamilton anxiety scale

The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) contains fourteen items distributed in two groups, the first group with seven items related to symptoms of anxious mood; Insomnia; depressed mood: loss of interest, mood swings, depression, early awakening;) and the second group, also composed of seven items, related to the physical symptoms of anxiety (motor somatization; sensory somatization; cardiovascular symptoms; respiratory symptoms; gastrointestinal symptoms; genitourinary symptoms and neurovegetative symptoms). The HAM-A was tested for reliability and validity in two different samples, one sample (n = 97) defined by anxiety disorders, the other sample (n = 101) defined by depressive disorders. The reliability and the concurrent validity of the HAM-A and its subscales proved to be sufficient. Internal validity tested by latent structure analysis was insufficient. The major problems with the HAM-A are that (1) anxiolytic and antidepressant effects cannot be clearly distinguished; (2) the subscale of somatic anxiety is strongly related to somatic side effects. The applicability of the HAM-A in anxiolytic treatment studies is therefore limited. More specific anxiety scales are needed.

State-Trait anxiety inventory

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a self-report scale that depends on the subject's conscious reflection in the process of evaluating their anxiety state, as well as their personality signed the Free and Informed Consent Form. Patients were asked to answer the Brief Inventory of Psychopathological Symptoms (BSI), the Defense Styles Inventory (DSQ-40), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM -A) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Patients were also asked to record a statement about the experience of anguish. This recording was listened to and analyzed to determine whether the patients were experiencing anguish or not.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis included descriptive and inferential analysis. The first step of the descriptive analysis was the objective of comparing the groups with and without anguish with numerical and categorical variables. The second stage consisted of examining the variables of the questionnaires. The third stage included the comparison of the anxiety and depression symptoms most associated with anguish. The inferential analysis consisted of two stages. The first stage focused on reducing the size of some questionnaires and constructing more discriminative latent variables in relation to groups with and without anguish. In the second stage, the variables with the greatest predictive power for discomfort were identified. characteristics. State anxiety scores can vary in intensity over time, are limited to a particular moment or situation, and individuals with state anxiety tend to become anxious only in particular situations.19 It is characterized by unpleasant feelings of tension and apprehension, consciously perceived, and can vary in intensity, depending on the danger perceived by the person and the change over time. Trait anxiety refers to relatively stable individual differences in the tendency to react to situations perceived as threatening with increases in the intensity of the anxiety state. It has a lasting characteristic in the person because the personality trait is less sensitive to environmental changes and because these remain relatively constant over time. The STAI-T has a valid and reliable psychometric instrument in terms of screening for anxiety disorders in PWEs. In the epilepsy setting, STAI-T maintains adequate sensitivity, acceptable specificity, and high NPV but low PPV for diagnosing anxiety disorders with an optimum cutoff score ≥ 52.

Table 1 shows that only the variable BSI Somatization was considered significant and, among the categorical variables, the variables that presented the greatest significance were the variables gender, level of education, HAM- A Fears, HAM-A Depressive Mood, HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms and HAM-A Neurovegetative Symptoms.

Anguish affects more women than men. The descriptive level of the Chi-Square test (p=0.041) also contributes to the evidence of this association between anguih and gender. Regarding marital status, it was found that there were no notable differences between the groups, with the sample being mostly single people.

Regarding the BSI questionnaire, only the distribution of the somatization variable was noticeably different between the groups. The median of the group with anguish is higher, in addition, the p-value of the Wilcoxon Mann Whitney test was significant (p = 0.02).

Regarding the HAM-A, the variables fears, depressive mood, gastrointestinal symptoms and neurovegetative symptoms showed significant differences for the variable anguish (individual significance level, Cronbach's α of 0.05), with the group with anguish being the one with the highest values of punctuation.

In summary, the variables that showed the greatest relationship with anguish were: gender, BSI somatization; HAM-A fears, depressed mood, gastrointestinal symptoms, and neurovegetative symptoms Table 2.

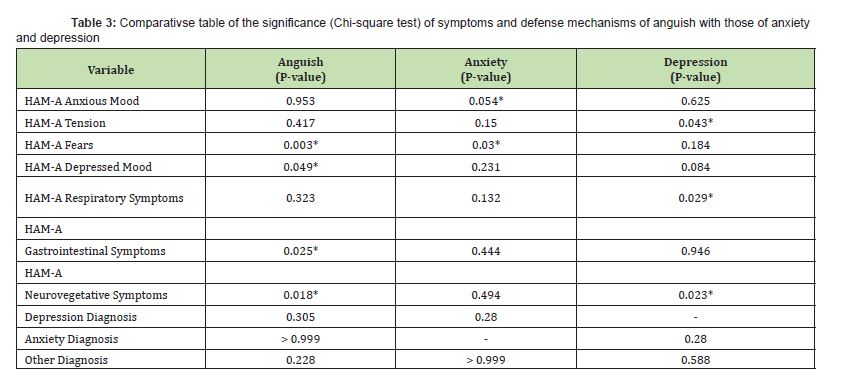

No variable related to anxiety was associated with anguish in this first descriptive context. As for depression, only the HAM- A variable, “depressive mood”, was significant. An analysis to compare the symptoms of anxiety and depression (using the MINI as a diagnosis) most associated with anguish was also carried out to discover what symptoms the two disorders have in common with anguish. The Wilcoxon Mann Wtihney and Chi-square tests show the association between the other variables and each of the three mentioned. Between anguish and depression, the variables BSI Somatization and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms were considered significant, and between anguish and anxiety, only the HAM-A variable fears was significant Table 3.

The inferential analysis consisted of three steps. The first stage focuses on reducing the size of some questionnaires and the construction of latent variables, possibly more discriminative in relation to groups without distress and distress, and for this purpose the Item Response Theory was used. The second stage aims to identify which variables have the greatest predictive power for anguish. Item Response Theory (IRT) was used to reduce the size of the HAM-A and DSQ-40 questionnaires. For HAM-A, two scores were generated through IRT. The first (Hamilton TRI Score) was applied to all 13 variables, the second (Reduced Hamilton TRI Score) was applied only to the most significant variables for distress in the Chi-square tests and also of interest to the researcher, namely: HAM -A Fears, HAM-A Depressive Mood, HAM-A Gastrointestinal Symptoms and HAM-A Neurovegetative Symptoms. Two Scores were also constructed by simple sum: HAM-A Sum Score and HAM-A Reduced Sum Score, the latter being constructed by the variables mentioned above. It is possible to see two points by observing the graphs. The first is that the HAM-A questionnaire actually has a relationship with the variable anguish, the second is that the difference between the two methods is clear, in which the IRT proved to be superior to the simple sum in terms of discriminatory power. of the groups. The DSQ-40 has 3 latent variables according to the literature: Neurotic DSQ, Immature DSQ and Mature DSQ, which are described in the section dedicated to the description of the variables. The DSQ, both via the sum and via the TRI, appears to have no relationship between the groups with and without anguish.

To investigate whether anguish is more related to depression than to anxiety, a logistic regression model was adjusted in which the response variable (dependent) was defined as having or not having anguish depending on many independent variables considered in the study. The model was adjusted without the doubt group, therefore, for 85 observations, with the variable distress being the response variable and the following 23 explanatory variables: DSQ-40 mature TRI score; immature DSQ-40 TRI score; TRI neurotic DSQ-40 score; reduced Hamilton score TRI; IDATE State; IDATE Trait; MINI depression; MINI anxiety; MINI other diagnosis; BSI somatization; BSI obsession compulsion; BSI depression; BSI anxiety; BSI hostility; BSI phobic anxiety; BSI paranoid ideation; BSI psychoticism; BSI interpersonal sensitivity; HADS anxiety; Age; Gender; Education level; Marital status. The selected variables were the following: Gender, Reduced Hamilton Score, BSI Somatization, BSI Hostility, BSI Obsession Compulsion, Age and MINI Depression.

Higher BSI Somatization scores are also associated with greater chances of having anguish, with each increase of one point in this domain the chance of anguish increases by 9.4%, keeping the other variables fixed. A 1-year increase in age reduces the expected chance of experiencing anguish by 4.6%, keeping other variables constant. The higher the HAM-A Score, the greater the expected chance of having anguish, that is, with each increase of one point in this Score there is an increase in the expected chance of anguish of 185%, considering the other variables in the model constant. For BSI Hostility, for each increase of 1 point, the expected chance of experiencing anguish decreases by 15.5%, keeping the other variables fixed. For BSI Obsession Compulsion, with each increase of 1 point, the chance of having anguish decreases by 12.6%, keeping the other variables fixed. The expected chance of women experiencing anguish is greater compared to men (the chance for women is 2.76 times greater than that for men), considering other variables constant. The estimates obtained indicate that the expected chance of people with depression experiencing anguish is greater in relation to those who do not present this symptom (the chance for people with depression is 3.64 times greater in relation to people without depression), keeping the other variables in mind.

This investigation aimed to prove the existence of differences regarding symptoms and comorbidities with regard to anguish, and that anguish is more related to depression than to anxiety. Based on the first hypothesis, it was concluded that the symptoms that are most linked to anxiety are: BSI somatization, HAM-A fears, HAM-A depressed mood, HAM-A gastrointestinal symptoms and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms. Regarding the second hypothesis, it appears that of the 82 patients with depression, 87.2% had anguish, while of the 69 patients with anxiety, 69.2% had anguish, indicating a higher frequency of anguish among patients with depression.

Regarding the hypothesis of differences in symptoms and comorbidities between patients with anguish and patients without anguish, we can verify that the experience of anguish is related to somatic symptoms that include thoughts and emotional states in conflict and that cause pain in the body such as aches and pains. head, back and chest, stiffening of the limbs, tachycardia, among others. Among patients who experienced anguish, chest pain was the most frequent somatic symptom. As for the HAM-A variables that showed significance, a significant relationship was noted between the HAM-A variable depressed mood and the HAM-A variables gastrointestinal symptoms and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms with regard to the experience of anguish. Another HAM-A variable that proved to be significant between patients with distress and patients without anguish was the HAM-A variable fears. Since patients who reported the experience of anguish complained of pain or tightness in the chest region, main characteristics of anguish, fear in this context is not fear of a specific object, such as an animal, natural environment or specific situation, but rather the fear of dying due to the experience of anguish. As Assumpção Júnior14 argues, anguish is more related to the fear of sudden death. In relation to the gastrointestinal and neurovegetative symptoms which, together with the depressed mood symptom which proved to be significant in the context of the experience of anguish, the first involve problems that are related to the anguish, namely the burning sensation or heartburn, abdominal fullness, nausea and vomiting, while among the neurovegetative symptoms, the problems that are more related to anguish include pain, malaise, discomfort, burning, heaviness, tightness, swelling or distension in a specific organ, which in this case is the chest region . The Hamilton Anxiety Scale was also subjected, based on the application of Item Response Theory to dimensionality reduction to find more interesting properties than the simple sum of correct answers and it was concluded that, after dimensionality reduction, i.e. after selecting the HAM-A variables that are most related to anguish, these appear to be more significant compared to the simple sum of correct answers, indicating that, especially the variables HAM-A depressed mood, HAM-A fears, HAM -A gastrointestinal symptoms and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms have significance regarding the experience of anguish. The greater significance of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale variables, as well as the BSI somatization variable, is also proven with the application of the Binomial Logistic Regression Model, which serves to select the independent variables and predict which group a patient is more likely to belong to. based on the independent variables.

As for the second hypothesis, which concerns the greater frequency of anguish among patients with depression compared to patients with anxiety, this can be proven based on the statements given by patients, which refer more to depression than to anxiety. Anguish is a feeling that causes bodily sensations such as tightness in the chest in situations that occur in the present moment, and the vast majority of patients declared having experienced anguish in present moments, such as loneliness, death of relatives, divorce, unemployment, high workload. work, difficulties in carrying out a task, sadness and thoughts about suicide, fear and insecurity, hopelessness, loss of control, problems related to work, family differences, despair, difficulty crying, physical illnesses, depression, travel, lack of emotional control, sad news, disappointments, bullying, parental rejection, political problems, feelings of oppression, crises due to psychiatric illnesses, stress, emotional pressure, accidents in the family, among others. Another result that reinforces the relationship between anguish and depression is given by the comparative analysis of significance, whose objective was to verify which variables are in common between anguish and depression and between anguish and anxiety, in which it was found that between anguish and depression, the common variables were BSI somatization and HAM-A neurovegetative symptoms, while between anguish and anxiety, only the HAM-A fear variable was common. This result reinforces the theory that anguish is more related to depression than to anxiety, since anguish is a feeling that encompasses somatic manifestations, reaching the conclusion that it is a visceral and physical feeling, while anxiety is a more psychic feeling. Based on the binomial logistic regression model, it is also possible to verify the greater significance among patients with depression compared to patients with anxiety regarding the experience of anguish, in which it can be concluded that, after applying the model, patients with depression have 3.64 more likely to experience anguish than patients with anxiety. The biblical accounts also follow the direction of the relationship between anguish and depression, since the characters mentioned in the introduction to this research experienced, in addition to anguish, loneliness, fear, the desire to die and psychological suffering, that is, symptoms linked to depression.

Another result indicating a greater relationship between anguish and depression than between anguish and anxiety concerns gender, in which it is found that anguish has a greater presence in females, despite the sample being made up mostly of women. However, judging by the proportion of women and men who experienced anguish, it can be concluded that anguish exerts greater force among women. The relationship between the higher prevalence of anguish among females and depression is justified by the higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among women, since data indicates that women have twice as much depression as men and try twice as much to suicide. According to data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health, depression affects 14.7% of women, while men are affected by 7.3%.

Anguish is the combination of emotional and physical issues that can reach the limit of preventing human beings from carrying out daily tasks or causing isolation. It is a negative sensation that can trigger many other psychological processes that can also become physical. An anxiety crisis manifests itself when the person experiences profound suffering, caused by one or more situations that are difficult to overcome. It can also be the result of other psychological disorders, such as anxiety, stress or depression. Anguish can be understood as a series of sensations that happen at the same time: physical sensations, such as shortness of breath, dizziness, pressure in the chest, accelerated heartbeat, and also psychological sensations, such as negative thoughts, guilt, crying, fear, sadness and anxiety. Also characterized by a strong negative feeling that seems to have no end, anguish usually appears without an apparent cause. It can cause physical symptoms such as tightness in the chest, feeling of a lump in the throat, weight on the shoulders and back of the neck, muscle tension, feeling of a hole in the stomach, among others. The feeling of anguish can be perceived as a state of depression, further intensifying the pain felt and can increase the risk of developing it. This anguish puts us in front of our own existence and fear, so the recognition of the freedom of our choices arises. Anguish is a disturbing and uncomfortable emotional manifestation that, because it manifests itself through symptoms similar to other problems, is often confused with anxiety, panic, depression and heart problems. Therefore, it is important to highlight the relevance that the concept of anxiety may have within the scope of HiTOP (Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology) and Rdoc (Research Domain Criteria). To this end, it is necessary to clarify both diagnostic systems. HiTOP comprises a new dimensional classification system for a wide range of psychiatric problems that has been developed to reflect cutting- edge scientific evidence. The diagnosis is important because it defines groups of patients who will receive treatment and public assistance. It is used by pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs and guides overall research efforts. In recent years, there have been clashes over psychiatric diagnosis. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) was published in 2013 and immediately divided medical opinion. The DSM-5 is an APA (American Psychiatric Association) guide on how to diagnose mental disorders. It has many critics, including the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), which in response has produced an alternative model to guide research efforts. However, this approach has also been controversial as it focuses heavily on neurobiology and much less on investigating issues important to everyday psychiatric care, such as symptoms and course of illness. The HiTOP system was articulated to address the limitations currently plaguing psychiatry. First, the system proposes to view mental health as a spectrum. Mental health problems are difficult to classify, as they are on the continuum between pathology and normality, just like weight and blood pressure. Applying an artificial threshold to distinguish what is healthy behavior versus mental illness results in unstable diagnoses because one symptom can change the diagnosis from present to absent. It also leaves a large group of people with symptoms that do not reach the threshold without treatment, although they suffer significant impairment. Secondly, the HiTOP system simplifies sorting. Different DSM-5 diagnoses co-occur with surprising frequency, with most patients labeled with more than one disorder at the same time. Furthermore, many diagnostic categories are so complex that often two patients with the same diagnosis do not share a single symptom in common. The HiTOP solution to these fundamental problems is to classify the dimensions of psychopathology into several levels of hierarchy. This allows doctors and researchers to focus on more detailed symptoms or evaluate broader problems as needed. For example, social anxiety disorder is a category in the DSM-5, while the HiTOP model describes it as a graded dimension, ranging from people experiencing mild discomfort in some social situations (e.g., when giving a talk in front of a large audience) for those who are extremely fearful in most situations. The HiTOP system recognizes that clinical levels of social anxiety are not fundamentally different from regular social discomfort. It also does not treat social anxiety as a single problem, but recognizes important differences between interpersonal fears (e.g., meeting new people) and performance fears (e.g., performing in front of an audience). Additionally, people with social anxiety are prone to other anxieties and depression, and the HiTOP model describes a broad spectrum called internalization that captures the overall severity of such problems. Thus, while the narrow level of hierarchy may provide good targets for symptom-specific treatments (e.g., public speaking), the higher level of hierarchy is useful when designing comprehensive treatment packages and developing public health policies. Unlike the DSM-5, the HiTOP project follows the most up-to-date scientific evidence rather than relying on expert opinion. HiTOP effectively summarizes information about shared genetic vulnerabilities, environmental risk factors, and neurobiological abnormalities. For example, it is becoming increasingly clear that genetic risk factors do not adhere to diagnostic categories; rather, genetic research identifies broad genetic risk factors that cut across diagnoses and broadly align with the HiTOP dimensions.20 As for RDoC, it consists of a research framework rooted in neuroscience with the goal of deepening understanding of the transdiagnostic biobehavioral systems underlying psychopathology and ultimately informing future classifications. The biobehavioral framework of RDoC can help elucidate the foundations of the clinical dimensions included in HiTOP.21 The contribution of distress to the HiTOP and RDoC diagnostic systems may be based on the results obtained from the research. It is concluded that anxiety is related to neurovegetative symptoms, which means that people who experience anxiety may present problems that include altered functioning, hyper- or hypo-functioning, such as palpitations, sweating, hot or cold flashes, tremors, as well as by expression of fear and disturbance at the possibility of a physical illness; gastrointestinal symptoms, and this group of symptoms includes problems such as chest pain, chronic and recurrent abdominal pain, dyspepsia, dysphagia, feeling of lump in the throat, halitosis, hiccups, nausea and vomiting; cardiovascular symptoms, which include problems such as pain or discomfort in the center of the chest, difficulty breathing, feeling sick, feeling faint, dizziness, cold sweat, paleness; as well as other symptoms such as somatization; fears and depressed mood. The main symptom of distress is the sensation of pain or constriction in the thoracic region that has an emotional origin. Both the research results and historical data lead to the conclusion that anguish comprises a prelude to depression, and that it is not as linked to anxiety as initially believed, an idea that was based on the translation of the word angst to anxiety. Thus, anguish is important for psychopathology due to the fact that patients who experience the feeling also present problems such as chest pain and a feeling of strangulation or lump in the throat, as well as gastrointestinals, cardiovascular and somatic symptoms, fear, and depressed mood.

It is also important to reflect on the importance of anguish. Anguish is a disturbing and uncomfortable emotional manifestation, characterized by fear of the end, loss and emptiness, in addition to the feeling of profound helplessness. Its main symptoms are: constricted breathing, suffocation in the throat and chest, a feeling of emptiness, restlessness, pain in the heart region and an unconscious anxiety that something bad is going to happen. Anguish has its importance in the issue of self- knowledge and the development of emotional intelligence, vulnerability, lack of control and the art of relating to life, people and everyday situations. Human beings are born with the anguish of separation from their mother, the loss of security and an “eternal lap” and we die with the anguish of separation from people, life and the unknown, in other words, anguish is part of life and is natural It is healthy to live it, despite the discomfort. Anguish becomes pathological when the feeling of fear of loss, lack and end becomes oversized. This fear generates deep disbelief in relation to affection, new experiences, humanity and the act of existing and living life in a healthy and fluid movement. And we are afraid to act, afraid to follow and move towards the “new”. Anguish triggers the mechanism: fear (paralysis/discomfort) X desire (aggression/pleasure). Anguish brings clarity to unconscious truths and reveals to us patterns, postures and conditioned thoughts. It awakens emotions rooted in our life history that often repeat themselves. It is a fundamental instrument for self- knowledge and human development. And, most of the time, it is the starting point of recurring emotional states and automated behaviors. Anguish signals the “tightening” of repressed emotions that need to be made aware and released. “And everything we resist, persists.”

Future research can also stimulate conceptual analysis in the areas of psychiatry, psychology and other areas that are related to psychopathology, particularly that related to neurosciences, since the use of complex concepts in basic research, without their prior analysis, becomes sterile, which may be one of the causes for the scarce results in translational studies in psychopathology/neurosciences. It is also recommended that research be carried out with a larger database, as well as using more accurate strategies for diagnosing distress that provide greater precision in analyzes and greater discrimination of groups with and without distress and respective predictors.

The present study suffers from some limitations. First, socioeconomic status or ethnicity are not measured, but to our knowledge, they have not previously been associated with the experience of anguish. Secondly, the Portuguese version of the Psychopathological Symptom Inventory was used to the detriment of the lack of validation of this scale for the Brazilian population.

The present study suggests that the variables that were most related to anguish were: gender, reduced HAM-A score, BSI somatization, BSI hostility, BSI, obsession- compulsion, age and depression diagnosis. The inferential analysis showed evidence towards the main hypothesis of the investigation: “Depression is more related to anguish than anxiety”. It is worth highlighting the selection of the MINI depression variable using the stepwise method, which showed a significant association (at a level of 10%), with the interpretation that people with depression are more likely to experience anguish compared to people who do not have depression. However, in the selection of variables most associated with distress, no variable related to anxiety was statistically associated with anguish, with the exception of the domains of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale.

None.

This Research Article received no external funding.

Regarding the publication of this article, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- 1. Gentil V, Gentil M. Why anguish? Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2009:pp.1-2.

- 2. López Ibor J. Psychiatric causes of chest pain. In: Diaz-Rubio M, Macaya C, López-Ibor J (eds) Dolor Thorácico Incierto. Madrid: Fundación Mutua Madrilena. 2007.

- 3. Strachey J. On the nature of therapeutic action of psychoanalysis. International Journal of Psychoanalysis.1934;15:127.

- 4. Freud S. The psychic mechanisms of hysterical phenomena. In: Brazilian Standard Edition of Complete Psychological Works, Rio de Janeiro: Imago. 1893/1996;3.

- 5. Pessotti I. Ansiedade. São Paulo: EPU. 1978.

- 6. Pereira ME. C. O conceito de ansiedade. In: Hetem, Luiz Alberto; Graeff, Frederico. Transtornos de ansiedade. São Paulo: Atheneu. 2004:pp.3,11-12,23.

- 7. Berrios G. História de los sintomas de los transtornos mentales. México: Fondo de Cultura Econômica. 2008.

- 8. Brissaud É. Angoisse sans anxiété. Revue Neurologique. 1992;2:762.

- 9. Del Porto JA. Ansiedade e angústia. Encarte Especial Motivação n. 5. São Paulo: Lemos Editorial. 2002.

- 10. Freud S. Sobre os fundamentos para destacar da neurastenia uma síndrome específica denominada “Neurose de Angústia”, v. III. Edição Standard Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Imago. 1895/1996.

- 11. Hanns L. Dicionário comentado do alemão de Freud. Rio de Janeiro: Imago. 1996.

- 12. Rocha Z. Os destinos da angústia na psicanálise freudiana. São Paulo: Escuta. 2000.

- 13. Boutonier J. L’Angoisse. Paris: Presses Universitaries de France. 1949.

- 14. Assumpção Júnior FB. Phenomenology: the existentialist view. In: Fráguas Júnior, R. Psychiatry and psychology in the general hospital: the anxiety disorders clinic. São Paulo: Lemos editorial. 1994:pp.17-19.

- 15. Vieira FFP, Neto FL. Investigating the relevance of precordial pain and anguish for mental health. Brazilian Journal of Health Review. 2004;7(3):1-16.

- 16. Canavarro M. Psychopathological Symptoms Inventory (BSI) - A critical review of studies carried out in Portugal. In M. R. Simões, C. Machado, M. M. Gonçalves, & L. S. Almeida (Eds.), Psychological Assessment - Instruments validated for the Portuguese population, Coimbra: Quarteto. 2007;pp.305-330.

- 17. Gallani MC, Proulx Belhumeur A, Almeras N, et al. Development and Validation of a Salt Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ-Na) and a Discretionary Salt Questionnaire (DSQ) for the Evaluation of Salt Intake among French-Canadian Population. Nutrients. 2020;13(1):105.

- 18. Scaini CR, Vieira IS, Machado R, et al. Immature defense mechanisms predict poor response to psychotherapy in major depressive patients with comorbid cluster B personality disorder. Braz J Psychiatry. 2022;44(5):469-477.

- 19. Knowles KA, Olantunji BO. Specificity of trait anxiety in anxiety and depression: Meta-analysis of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Clin Psychol. 2020;82:101928.

- 20. Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, et al. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126(4):454-477.

- 21. Casey BJ, Craddock N, Cuthbert BN, et al. DSM-5 and RDoC: progress in psychiatry research?. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(11):810-814.