Background: Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional disorder in the world, and most prevalent in women of reproductive age. Iron supplementation is a common strategy currently used to control iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia in developing countries. However, it is not clear whether women actually ingest the supplements.

Objectives: To assess IFA utilization and factors associated with IFA utilization among pregnant women attending ANC at government health facilities and family guidance clinic in Hawassa city, South Ethiopia.

Methods: Facility based cross-sectional survey was conducted in March /2015. Sample size is determined by using single and double population proportion. Consecutive sampling technique was used to select study units. Data was collected by trained unemployed diploma nurses using a pretested structured questionnaire. It was cleaned and checked for completeness and then entered in to Epi-info 3.2.2 and exported to SPSS 16.o software for analysis. Predictors were found out using bivariate and multivariate logistic regression.

Results:A total of 412 pregnant women who came to attend ANC at least for the second time were interviewed in seven health facilities. Our study showed that 333 (81%, 95% CI: 77.2−84.8) pregnant women reported taking IFA supplement and compliance was 37.7% (95% CI: 32.5-42.9). In multivariable analysis, side effects and low acceptance of the supplement were significantly associated with high compliance to IFA supplementation (P < 0.05).

Conclusion: There was a better level of compliance towards IFA supplementation compared to other national data. Pregnant women should be counseled regarding how to manage the side of IFA supplement during ANC. Further research has to be done on the acceptability of the supplements.

Keywords: Anemia, Iron with folic acid, Compliance, Pregnant, Hawassa city

Iron deficiency (ID) is a state of insufficient iron to maintain normal physiological functions of tissues and leads to anemia.1 In addition, folate is an essential micronutrient in the human body All pregnant women in areas of high prevalence of malnutrition should routinely receive iron with folic acid (IFA) supplements, together with appropriate dietary advice to prevent anemia.2-4

Iron deficiency (ID) is the most common nutritional disorder in the world, affecting approximately 25% of the world's population.2 It is most prevalent and severe in young children and women of reproductive age. It plays an important role in socio-economic development of nations. Global estimates show that 42% of women are anemic.5

For women, the consequences of anemia are reduced levels of energy and productivity, impaired immune function, reproductive failure (miscarriage, still births, prematurity, low birth weight, per-natal mortality), and maternal death during childbirth.6

According to EDHS 2011, the total fertility rate of Ethiopia was 4.8 children per woman, and the prevalence of low birth weight was 11%.5 Beside, maternal mortality rate and infant mortality rate were high (114/100,000 and 59/1000, respectively).5

Antenatal care programs distribute iron supplements to pregnant women. However, the effectiveness of these interventions on reducing maternal anemia has been inadequate.7 In Ethiopia, <1% took iron supplements for the recommended period (90 days or more) during their last pregnancy.5 Many nutrition experts believe that one of the main reasons national iron supplementation programs have failed is women’s noncompliance with taking iron supplements daily because of gastrointestinal upset and other side effects that sometimes occur when taking iron. Recent reviews on the topic suggest that there are a number of reasons for ineffective programs including sporadic or inadequate supply, poor quality tablets, problems with delivery and distribution systems, poorly trained and uncommitted health providers, ineffective communication materials to promote behavior change, lack of access to or use of prenatal care, and poor monitoring of the problem.7-10

Iron supplementation is a common strategy currently used to control iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in developing countries including Ethiopia.6-8 Consequently, the National Nutrition Program (NNP) set a key target of increasing the proportion of mothers who get iron supplementation for more than 90 days during pregnancy to 50% by 2015.11

In SNNP, only 27% of women who gave birth in the five years preceding the survey received antenatal care from a skilled provider for their most recent birth and coverage of iron supplementation was 15%.5 We did not find information on the effective coverage of the IFA women received or purchased in the study areas. It is also not clear whether women actually use (ingest) the supplement and the factors associated with compliance in the study area.

Study objective

Thus, the purpose of the current study is to assess IFA utilization and factors associated with IFA utilization among pregnant women attending ANC at government health facilities and family guidance clinic in Hawassa city, South Ethiopia.

Study area

The study was conducted in Hawassa city, which is 275km south of Addis Ababa. Hawassa city is found in Sidama zone, South Ethiopia.

Study design and period

Facility based cross-sectional study was conducted on the utilization of IFA supplements and associated factors in March, 2015 in Hawassa city.

Source population

All pregnant women who are permanent residents for last six months.

Study population

All pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Hawassa city government hospitals, health centers and family guidance at time of data collection. The sample size was determined by the formula used for the unmatched case control study using EPI Info 7. Factors like age >25 years, low socioeconomic status, ANC >4, and cost of tablet were used, and a factor giving the largest sample size was used as the final sample size of the study (age >25 years). Assumptions used to estimate the sample size were the percentage of non-adherents with age >25 years 37.3%,12 a minimum detectable of odds ratio of 1.836, level of precision 5%, a power of 80%, with one -to-one ratio among cases and controls, considering 10% non-response rate and design effect of 1. The final sample size became 412.

Data collection procedure

Data was collected by using face-to--to-face interviews with pre-tested structured questionnaires initially prepared in English and translated to Amharic, and translated back to English by language experts. The independent study variables included were socio-demographic factors, health seeking behavior and utilization of supplementation services, environmental factors, and medical information. The dependent variable was utilization of iron containing supplement. Seven female research assistants who were unemployed and with training in nursing and two supervisors who had a first degree in health and experience in research were recruited. The questionnaire was pretested on 10% of the sample on other than the study area.

Data processing and analysis

The data analysis is done by using Statistical Package for Social sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 statistical software. Descriptive statistics was carried out to summarize the data. The main dependent variable was the compliance rate. Bivariate analysis was done to elicit factors associated with utilization of iron and folic acid supplementation with odds ratio as the measure of association. Factor having a p-value <0.25 in bivariate analysis were entered in the binary logistic regression model building process. A P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Operational Definition

Compliance

was defined as the use of supplements for more than eleven days from last in the previous 15 days preceding the interviewed date.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from School of Public Health and Medical Sciences Research and Ethics committee of Wolaita Soddo University. Formal letter of permission was obtained from Hawassa City administration health desk for each health facility. Respective health centers officially allowed carrying out the interviews. Finally, verbal consent was secured from each participant before the interview explaining the objectives of the study. Confidentiality was assured by indicating that they are not requested to write their name on the questionnaire and by assuring that their responses will not in any way be linked to them. In addition, they were told that they have the right not to participate and withdraw from the study in between.

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

A total of 412 pregnant women were interviewed in seven health facilities. The median age of the respondents was 25 years and about three fourths (74.2%) were between 20–29 years. About half of the women (52.1%) were protestant religion followers. Nearly all participants (97.8%) were married. About one-third (34.5 %) of the respondents were secondary school complete and 47.8% identified themselves as housewives. The median number of children ever born was two. Three hundred thirteen (87.4%) of the women responded their household average monthly income was greater than one thousand birr.

Factors associated with compliance to iron with folic acid supplementation pregnancy

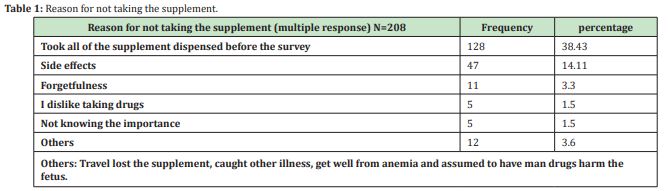

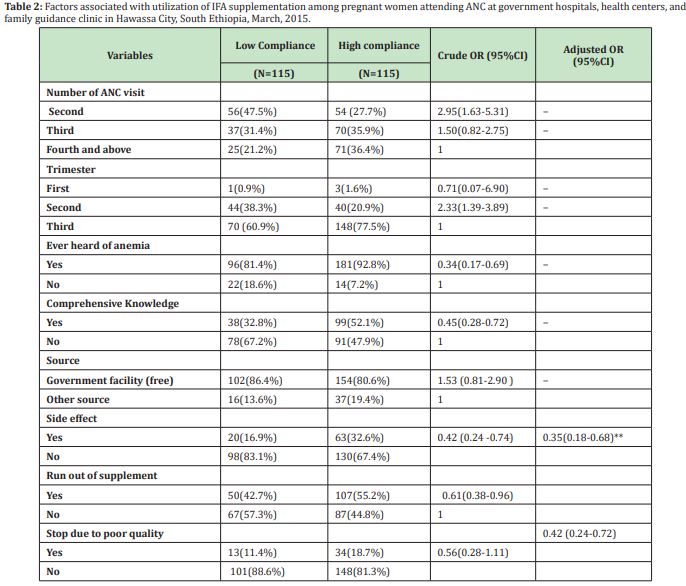

Table 1 Reason for missing one or more doses of iron containing tablets/capsule supplementation among pregnant women attending ANC at government hospitals, health centers, and family guidance clinic in Hawassa City, Ethiopia, March, 2015. Out of the candidate variables on bivariate analysis having p-value <0.25, only explaining the benefit of the supplement by health care providers, the poor quality of supplement, and side effects showed statistical significance on multivariate analysis Table 2.

WHO recommends all pregnant women in areas of anemia prevalence < 40% should routinely receive iron and folic acid supplements, which means ideally taking 180 tablets before delivery.7 However, our study showed that more than four-fifth (81%) of pregnant women took Iron containing supplement during the current pregnancy and the compliance was 37.7% (95% CI:32.5-42.9). Socio-demographic characteristics were not good predictors of compliance, and our findings confirmed this statement.10 Age of the woman, current marital status, and birth order and income variables did not have a significant effect on high compliance with IFA supplementation. Side effects and low acceptance of the supplement were important predictors of compliance with IFA supplementation.

This effective coverage (81%) of the IFA supplementation is high compared to the coverage of mini EDHS 2014 of urban consumption of iron tablets (41%).15 This difference may be due to the respondents were from health facility only and the study was carried out in the capital of south nations and the nationality of people region. In addition to that, the longer reference period used in the EDHS might have made it less sensitive to the very recent national level. However, WHO recommends that every pregnant woman has to receive a standard dose of iron and folic acid supplements.2,7

Ideally, women should receive iron-containing supplements no later than the first trimester of pregnancy as recommended by World Health Organization.2,7 However, we found that the supplementation initiation was late (4.2±1.3 months) on average during the fourth month of pregnancy but it is earlier than the study done in eight rural districts of Ethiopia 5.6 (±1.7) and this might be due to early first ANC visit.14 Early initiation and the total number of supplements consumed during pregnancy have a significant impact on child mortality.2

According to our study, 37.7 % of women have high compliance. This finding is lower than the compliance of 74.9% reported in Ethiopia, 69% in Senegal, and 58.1% in South India.14,16,17 This might be due to the low compliance of prescribers with the national micronutrient guideline. In addition, various studies use different definitions of compliance with IFA supplementation; hence, comparison among them is not a worthy.

Forget fullness is mentioned by 3.3% of women as a reason for missing one or more doses of iron containing tablets/capsules. It was found to be 78.8% in another study of compliance with IFA in Philippines18 and 48.8% in a South Indian,2 which is lower in this study might better self-care. Further, it can be prevented by supportive attitude of family members and compliance can be improved by developing an appropriate message and improving communication.19

Among the enabling factors, side effects and acceptability of iron and folic acid supplement was found to be significantly associated. Side-effect is frequently considered as a major obstacle to compliance.14,16-22 In our study, it observed that 80.9 % of women with low compliance reported side effect as the reason for low compliance. However, in Burma, only 3% of women stated that side effects were the reason they stopped taking iron supplements, while 30% of women in Thailand complained of side effects while taking iron tablets. Studies conducted in Philippines19 and Vietnam20 also concluded likewise. This might be due to the majority of women were not informed about the potential side effects of iron and folic acid supplements and how to minimize them in advance. The study also showed that 14.41% women not took the supplement due to poor quality of iron and folic acid tablets. This finding is supported by a study done in India.2,23,24

Effective coverage and compliance with IFA supplementation among pregnant women attending ANC at government hospitals, health centers, and family guidance clinic in Hawassa City was relatively high. Compliance is significantly associated with side effects and low acceptance of the supplement due to poor quality.

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest

Authors' contributions

FM carried out IFA utilization and factors associated with IFA utilization among pregnant women attending ANC at government health facilities and family guidance clinic in Hawassa city study by acquisition of funding, collection of data, general supervision of the research and made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published. LK made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data involved in drafting the manuscript, revising it critically for important intellectual content. AW made substantial contributions to the conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of data, involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

ANC Anti Natal Care

CI Confidence Interval

CSA Central Statistical Agency

DHS Demographic and Health Survey

EDHS Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

FMoH Federal Ministry of Health

ID Iron deficiency

IFA Iron with Folic acid

SNNPRS Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region State

WHO World Health Organization

Availability of data and materials

The spreadsheet data supporting the findings of this is available at the hands of the corresponding author which can be delivered to the journal based on request at any time.

Consent for publication

We agree to the terms and policies of the editorial office of the journal.

We would like to thank Wolaita Sodo University for facilitating the whole project work and NORHED-SENUPH project for financial support to conduct the study. We are also grateful to Hawassa city health department, health facilities included in the study, data collectors, and the study participant for delivering information regarding the study.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. WHO. The World Health Report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life: overview. Geneva, 2002.

- 2. INACG. Why iron is important and what to do about it: A new perspective. 2002.

- 3. Christensen RD, Ohls RK. Anemia unique to pregnancy and the prenatal period. In: Wintrobe’s clinical hematology. 2004:2(11th edn).

- 4. De Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anemia 1993–2005: WHO global database on anemia. Geneva: WHO, CDC; 2008.

- 5. Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, Measure DHS: Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa and Calverton: CSA Ethiopia and Measure DHS-ICF Macro; 2011.

- 6. Li R, Chen X, Yan H, et al. Functional consequences of iron supplementation in iron-deficient female cotton mill workers in Beijing, China. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1994;59(4):908–913.

- 7. WHO. Iron deficiency anemia assessment prevention and control: a guide for program managers. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2001;132.

- 8. Galloway R, Dusch E, Endang A, et al. Women’s perceptions of iron deficiency and anemia prevention and control in eight developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:529–544.

- 9. Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) of Ethiopia: National guideline for control and prevention of micronutrient deficiencies. Addis Ababa: FMOH; 2004.

- 10. Lacerete P, Pradipase M, Temchareen P, et al. Determinants of adherence to Iron/folate supplementation during pregnancy in two provinces in Cambodia. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2011;23(3):315–323.

- 11. Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia: National Nutrition program. Addis Ababa: FDRE; 2013-2015.

- 12. Lutsey P Dawe D, Villate E. Iron supplementation compliance among pregnant women in Bicol, Philippines. Public Health Nutrition. 2008;11(1):76–82.

- 13. Ogundipe O, Hoyo C, Ostbye T, et al. Factors associated with prenatal folic acid and iron supplementation among 21,889 pregnant women in Northern Tanzania: A cross-sectional hospital-based study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:481.

- 14. Gebremedhin S, Samuel A, Mamo G et al. Coverage, compliance and factors associated with utilization of iron supplementation during pregnancy in eight rural districts of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:607.

- 15. Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, Measure Mini DHS: Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2014. Addis Ababa. 2014.

- 16. Mithra P, Unnikrishnan B, Rekha T, et al. Compliance with iron-folic acid (IFA) therapy among pregnant women in an urban area of south India. African Health Sciences. 2013;13(4):880–885.

- 17. Seck BC, Jackson RT. Determinants of compliance with iron supplementation among pregnant women in Senegal. Public Health Nutr. 2007;11(6):596–605.

- 18. Eva Charlotte Ekström, SM Ziauddin Hyder, A Mushtaque R Chowdhury, et al. Efficacy and trial effectiveness of weekly and daily iron supplementation among pregnant women in rural Bangladesh: disentangling the issues. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1392–1400.

- 19. Nisaret Y, Dibley M, Mir M. Factors associated with non-use of antenatal iron and folic acid supplements among Pakistani women: a cross sectional household survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14:305.

- 20. Ritsuko A, Jimba M, Nguen K, et al. Why do adult women in Vietnam take iron tablets? BMC Public Health, 2006;6:144–152.

- 21. Gebre A, Mulugeta A, Etana B. Assessment of Factors Associated with Adherence to Iron-Folic Acid Supplementation Among Urban and Rural Pregnant Women in North Western Zone of Tigray, Ethiopia: Comparative Study. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences. 2015;4(2):161–168.

- 22. Jasti S, Siega A, Cogswell M. Pill count adherence to prenatal multivitamin/mineral supplement use among low-income women. J Am Soc Nutr Sci. 2007;2:1093–1101.

- 23. Gibson R, Hotz C. Dietary diversification/modification strategies to enhance micronutrient content and bioavailability of diets in developing countries. British Journal of Nutrition. 2001;85(2):159–166.

- 24. Population Census Commission of Ethiopia. Summary and statistical report of the 2007 population and housing census of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: CSA, 2008.