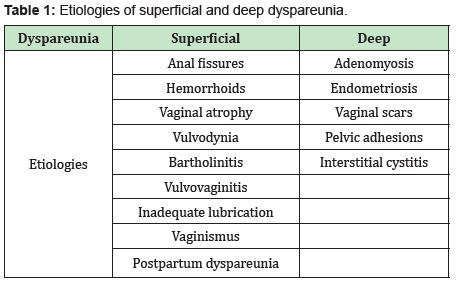

Dyspareunia is a common, but little-known, chronic problem, described as persistent or recurring pain that occurs during sexual intercourse.1 It is a multifactorial pathology that involves psychological, biological and social factors. The incidence of dyspareunia is difficult to determine because women do not usually resort to consultation. The prevalence is around 10% of women of childbearing age and 45% of postmenopausal women.2 Estrogen deficiency can lead to vaginal atrophy, the symptoms of which include vaginal dryness as well as dyspareunia, burning, and dysuria; urgent urinary symptoms, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).3 Dyspareunia can be classified in different ways: depending on the moment in which the pain appeared (primary or secondary), in the situational context (generational or situational) and the one that is most used today in clinical practice is based on its location (superficial or deep). This classification allows us to distinguish between the variable causes of dyspareunia and reduces differential diagnoses. 1 Superficial dyspareunia is defined as pain when attempting vaginal penetration into the introitus, whereas in deep dyspareunia, pain is felt on vaginal penetration.Possible causes are listed in the following Table 1.

Due to this, women generally suffer alterations in their mood and feel distressed by changes in sexual function. Therefore, it is important that the doctor inquireabout their sexual health and that the sexual concerns of the women are normalized and universalized. 4 Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects approximately 27% to 84% of postmenopausal women and can significantly affect their health, sexual function, and quality of life.5 The diagnosis of GSM includes questioning and vaginal examination. Because the majority of women do not report these events, because they attribute it to physiological changes of aging, it is recommended to inquire about these symptoms in all perimenopausal and postmenopausal women including the collection of useful data such as time of onset, duration, levels of associated distress, how it affects their quality of life, their sexual activity and the relationship with their partner. Data was collected by the Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & attitudes (VIVA-LATAM) survey,6 in which 2509 women from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico between 55 and 65 years old participated. The data showed that generally they had little knowledge about vaginal atrophy. However, the majority of the surveyed population (79%) were aware of the treatment options, mainly lubricating gels and creams (59%). The CLOSER survey7 considered the impact of vaginal discomfort and its treatment on the self-esteem of postmenopausal women and intimate relationships between postmenopausal women and their partners. The answers revealed that vaginal discomfort had a negative impact on intimate relationships.Vaginal discomfort made the majority of women (58%) avoidintimacy and experience loss of libido. On the men's side, a higher percentage (78%) believed that vaginal discomfort caused their postmenopausal partners to avoid intimacy. Vaginal discomfort also had a negative effect on the self-esteem of postmenopausal women, and almost one third no longer felt sexually attractive and lost confidence in themselves as a sexual partner.

During the vaginal examination a decrease in the volume of the pubic mound, of the labia majora, decreased tissue and pigmentation of the labia minora and prominences (telescopic), and erythema of the urethral meatuscan be observed.8 The proposal of incorporating sexuality into clinical practice provides strategies for the identification, assessment, and/or referral to a specialist physician for sexual health problems. The treatment of dyspareunia is individualized and should include a shared decision-making approach, the main objective being to alleviate symptoms. First-line treatment is based on non-hormonal vaginal and vulvar lubricants with sexual activity (recommendation A) and vaginal moisturizers of prolonged action.However, there are few studies on the efficacy of these overthe- counter products in the population. The use of pharmacological treatments can provide greater benefits and is indicated when non-hormonal therapy has not been effective and symptoms are severe. These include local hormonal therapy (low-dose vaginal estrogens, dehydroepiandrosterone vaginal) and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as oral ospemifene.9

Local estrogen therapy (TEL) causes improvement in symptoms and restores vaginal physiology. All estrogens are effective and safe. TEL should be individualized, given once daily for two weeks and then three, two, or once weekly. It can be prescribed with tablets, ovules, pessaries, creams or vaginal rings containing estradiol, estriol, estrone, or conjugated estrogens with equal efficacy. 10,11 The products vary in dosage and formulation, compared to creams, 17β-estradiol 0.01% (0.1mg active ingredient/g) can be used with an initial dose of 0.5-1 g for 2 weeks, conjugated equine estrogens(0.625)mg active ingredient/g) with a starting dose of 0.5-1 g for 2 weeks or 0.1% estrone (1 mg active ingredient/g) with a dose of 0.5-4g planned for short-term use.12 Regarding vaginal inserts, estradiol 17βinserts 4-10 g can be used for 2 weeks or estradiol hemihydrate tablets 10 g for 2 weeks.13,14 Intravaginal Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) 5% (6.5mg) is used for postmenopausal women with moderate to severe dyspareunia caused by vulvovaginal atrophy.

Its most common adverse effect is vaginal discharge, and it is recommended for use every night for approximately 3 months.15 Another of the drugs used is promestriene, whose advantage is the lack of vaginal absorption. The dosage will depend on each individual woman but it is advisable to start with an attack dose (1 capsule/day vaginally, for 20 days, 2 times/week until symptoms regress) and then continue with maintenance until the woman feels like she no longer needs it. If the dryness is very important or the dyspareunia is superficial, the addition of promestriene cream is recommended to complement the treatment with ovules (1-2 vulvar application/day, for 7 days, 2 times/week until symptoms regression). In reference to selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as ospemiphene, they are not available in Argentina and are systematically indicated for moderate to severe dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvovaginal atrophy, with favorable effects on bone density.16 Currently the vaginal laser can also be used. It is an option to avoid hormonal interventions.17 The laser remodels deep collagen, thus promoting collagen synthesis. This effect results in better tissue integrity and elasticity after 3 laser cycles are performed CO2.18 The improvement of the symptoms could take from 1 to 3 months and ongoing treatment is generally required due to the high probability that symptoms will reappear when treatment is discontinued. Other considerations that may influence individual treatment options include cost of the treatment, ease of obtaining treatment, and patient´s personal preferences regarding vaginal treatment options.

In conclusion, dyspareunia is an affectation that alters a full and satisfactory sexual life, which has an emotional impact on both women and their partners. It is necessary for women to discuss these issues with their doctors in order to promote and restore the well being of our patients. There is a wide variety of treatments to restore the patient's state of well-being and emotional improvement.

None.

None.

No conflict of interest for any of the authors.

- 1. AlimiY, Iwanaga J, JoskouianR. The clinical anatomy of dyspareunia: a review. Clin Anat. 2018;31(7):1013‒1017.

- 2. Kumferber B. Dispareunia:desvelando sus misterios. Presentation presented. 2020.

- 3. Krychman M, Graham S, Bernick B, et al. The women’s EMPOWER survey: women’s knowledge and awareness of treatment options for vulvar and vaginal atrophy remains inadequate. J Sex Med. 2017;14:425‒433.

- 4. Faubion S, Larkin L, Stuenkel C. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer :consensus recommendations from the North American Menopause Society and The International Society for the study of women’s sexual health. Menopause. 2018;25(6):596‒608.

- 5. Lee N, Jakes A, Lloyd J. Dyspareunia. BMJ. 2018;361:k2341.

- 6. RE Nappi, NR de Melo, M Martino. Vaginal Health:Insights,Views &Attitudes(VIVA‒LATAM)results of a survey in Latin America. Climacteric. 2018;21(4):397‒403.

- 7. James A Simon, Rosella E Napp.Clarifying Vaginal Atrophy´S Impact On Sex And Relationships (CLOSER) Survey:Emotional And Physical Impact Of Vaginal Discomfort On North American Postmenopausal Women And Their Partners. Menopause. 2014;21(2):137‒42.

- 8. Kagan R, Kellogg‒Spadt S, Parish SJ. Practical treatment considerations in the management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Drugs Aging. 2019;36:897‒908.

- 9. Nappi RE, Davis SR. The use of hormone therapy for the maintenance of urogynecological and sexual health post WHI. Climacteric. 2012;15:267‒274.

- 10. The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728‒753.

- 11. Gorodeski GI. Estrogen modulation of epithelial permeability in cervi‒ cal‒vaginal cells of premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Meno‒ pause. 2007;14:1012‒1019.

- 12. Manonai J, Theppisai U, Suthutvoravut S, et al. The effect of estradiol vaginal tablet and conjugated estrogen cream on urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: a comparative study. J ObstetGynaecol Res. 2001;27:255‒260.

- 13. Notelovitz M, Funk S, Nanavati N, et al. Estradiol absorption from vaginal tablets in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:556‒562.

- 14. Eugster Hausmann M, Waitzinger J, Lehnick D. Minimized estradiol absorption with ultra‒low‒dose 10 microg 17beta‒estradiol vaginal tablets. Climacteric. 2010;13:219‒227.

- 15. Krychman ML. Vaginal estrogens for the treatment of dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2011;8(3):666–674.

- 16. Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA. Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atro‒ phy. Menopause. 2013;20:623‒630.

- 17. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fractional laser treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and US Food and Drug Adminis‒ tration Clearance. 2018.

- 18. Filippini M, Luvero D, Salvatore S, et al. Efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in postmenopausal women with genitourinary syndrome: a multicenter study. Menopause. 2020;27:43‒49.