The correct and effective management of wounds remains challenging within the wound care discipline even though much effort and attention has been directed toward novel technologies and advanced approaches. As wound healing takes place in four stages, the selection of the appropriate treatment, depending on the respective stage on the patients’ wound, is crucial. In addition, identifying the type of wound might be difficult in some cases, which in combination with the aforementioned further complicates appropriate wound management. This article discusses a single product wound management, by means of case studies, in an attempt to describe a simplified and possibly cost-effective way to manage wounds effectively.

Keywords: Wounds, Healing, Honey, Wound healing phases, Dermatological application

The efficient and proper management of wounds remains a clinical problem, frequently causing morbidity and mortality due initial and delayed complications. Consequently, a substantial amount of research has been conducted to identify and continuously develop novel therapeutic approaches and technologies for the management of acute and chronic wounds.1 The development of new approaches however requires understanding the physiological trajectory of normal wound healing,2 described as the phases of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. The wound healing process is a complicated and intricate process. The stages of wound healing do not occur in isolation as considerable overlapping transpires between the stages. Wound healing, sometimes called the healing cascade, is generally described in four distinct phases.

Homeostasis: When incurring a wound, the first phase of the wound response is concerned with maintaining homoeostasis within the body. Most wounds, even superficial shallow wounds, lead to damage to the vascular system. To manage blood loss and reduce the possibility of infection spreading throughout the body, circulation platelets within the blood begin to form a fibrin clot, which seals the wound site. Additionally, vasoconstriction primarily occurs around the wound site as a means of isolating the wound site. However, this is followed by vasodilation, so the required cells can be recruited to the wound site. Growth factors are released from damaged cells, and those around the wound site upregulates a rapid inflammatory response.

Inflammation: Immune cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, are attracted by factors released from the wound site and begin to accumulate, travelling through the circulatory system. These cells are responsible for the removal of debris and killing of bacteria that easily colonize the wound site and prepare the wound for the proliferative / remodeling phase.

Proliferation: The proliferative phase can be divided into four phases; in the case of superficial wounds the initial two steps may not occur:

- Re-vascularisation: New blood vessels are formed around the wound site to provide the cells and nutrients essential to remodel the wound.

- Granulation: Fibroblasts drawn to the wound site rapidly form temporary extra cellular matrix, comprised of collagen and fibronectin, upon which the epidermis is reconstituted.

- Re-epithelialization: The mechanism of re-epithelialization is poorly understood. It’s thought that surviving epithelial cells around the edges of the wound bed become more motile and stretch to cover the wound site. When a continuous epidermis is formed, the cells lose this motility and start to divide.

- Contraction: Re-epithelization is believed to occur simultaneously with contraction, where myo-fibroblasts recruited around the wound site pull against each other to contract and reduce the dimensions of the wound.

Remodelling: Following closure of the wound, remodelling can occur. The epidermis proliferates and returns to its normal character; fibroblasts and immune cells which were recruited to the site are degraded; and therefore, the temporary extra cellular matrix that was laid down is remodelled into a stronger, more permanent structure.3

These four highly programmed, integrated and overlapping phases, are required to occur in a specific time frame and sequence, for successful wound healing to occur.4 Numerous factors can cause a disruption or affect one or more of these stages,1 resulting in a non-healing chronic wound or delayed wound healing.4 The latter has through history been a global concern due to the distress and discomfort it causes to the patient.5 Subsequently to the rate of wound healing and especially in aesthetically sensitive locations the degree of scarring post wound healing become an important factor to consider due to the life-long psychological and or functional implications it may have on the patient.6 Although novel wound care techniques such as negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been developed and implemented with great success in the past two decades, certain individual patient related factors can necessitate the consideration of other therapies. A study performed by Fagerdahl5 highlighted patient experiences with the use of negative pressure wound therapy, these areas included i.e. the affect this therapy had on the patients personal environment (physical, mental, social and spiritual aspects). Other important factors to either manage or consider is existing infection or the possibility of occurring infection, as a wound causes the skin to be impaired and therefore highly susceptible to bacterial infiltrations. By preventing or treating these infections effectively, it can significantly improve the wound healing,7 however accomplishing this task has become a difficult endeavor in the modern age, due to the increasing amount of antibiotics that because of bacterial resistance is rendered effective. Hence, exploring alternative therapies becomes increasing crucial, and although many exists, implementation thereof may be challenging.8

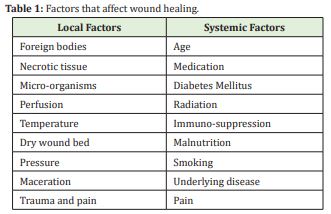

Factors that affect wound healing

The time required for a wound to progress duffers dramatically on local and systemic factors as outlined in the Table 1 below.

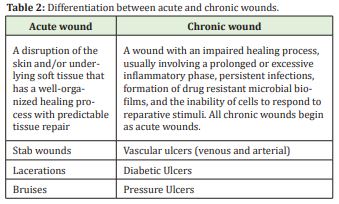

Acute wound

An acute wound occurs on a site with normal injury at a specific time from a known mechanism (burn, cut, etc.). Its depth is variable depending on the type of trauma. Acute wounds usually heal rapidly and uneventfully. An acute wound can become chronic (longstanding).

Chronic wound

A chronic wound is a wound that does not heal in an orderly set of stages and in a predictable amount of time the way most wounds do. Wounds that do not heal within three months are often considered chronic. Chronic wounds seem to be detained in one or more of the phases of wound healing. Chronic wounds often remain in the inflammatory stage for too long. To overcome that stage and jump-start the healing process several factors need to be addressed such as bacterial burden, necrotic tissue, and moisture balance of the whole wound. In acute wounds, there is a precise balance between production and degradation of molecules such as collagen; in chronic wounds this balance is lost and degradation plays too large a role.9

Some examples of acute and chronic wounds are:

- Pressures sores

- Low extremity ulcers

- chemical and radiation injuries

- burn wounds, which can be classified according to depth, i.e. superficial, partial thickness, full thickness and subdermal.

Types of wounds Some examples of acute and chronic wounds are:

• Pressure sores

• Lower-extremity ulcers wound care

• Chemical and radiation injuries

• Burn wounds, which can be classified according to depth, i.e. superficial, partial thickness, full thickness, sub-dermal. A full assessment of the wound bed is required before selecting a wound care dressing. The following factors should be taken into consideration:

• Size, depth, shape and location of the wound

• Amount of exudate

• Presence of an odour

• Presence of necrotic tissue

• Bacterial load.

By considering the above-mentioned factors the approach in the following case studies was utilizing a product containing an age-old remedy, honey.

Honey as a treatment for wounds

Since ancient times, honey has been utilised in the treatment of numerous infectious diseases, more specifically wound treatment. In addition, there has been no indication of the occurrence of microbial resistance, which contributes to the already beneficial properties posed by honey, as this provided an opportunity to investigate the uses of honey not only in everyday wounds, but also in wound infected with resistant strains of bacteria.

Although several factors contribute to the antimicrobial action of honey, the most significant contribution is due to:

- That the high sugar content (resulting in osmotic action)

- Acidic pH (3 - 4)

- The presence of flavonoids and antioxidants

- Production of hydrogen, due to the addition of an enzyme by the bee to the nectar

Honey is a complex mixture comprising of a multiple constituent such as:10

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

Carotenes

Methylgyoxal

Phenolic compounds that include, caffeic acid, kaempferol, ferulic acid, quercetin, chlorogenicellagic acid, benzoic acid, gallic acid, coumaric acid, monosaccharides, polysaccharides, amino acids, vitamins and minerals

Maillard reaction products (MRP’s)

Ascorbic acids

Lactic Acid

Catalysts

At a concentration of 50%, honey (primarily originating from the Western Cape) displayed a total inhibition of bacterial growth, on tested pathogens commonly associated with wounds tested:

- Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus),

- methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)

- gentamycin-resistant S. aureus,

- Staphyloccocus epidermidis,

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Gram negative)

The utilization of honey based topical product has reemerged in the past few decades, with more evidence and data supporting beneficial claims associated with the use of honey-based products on wounds such as the pH lowering effect on the wound, ability to penetrate bio-films, debriding capacity, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity.11

During the formulation of Wound Occlusive (honey-based ointment), the main focus was on creating a product that could be successfully utilized during all phases of wound healing, that is user friendly and that will minimalize scarring. Although Wound Occlusive contains 50% (w/w) honey, the formulation in its entirety contributes to the mechanism by which wound healing is facilitated by this product such as:

- Zinc oxide (shown to increase the rate of wound healing)12

- Xylitol (can inhibit or interfere with biofilm formation)13

- Hyaluronic Acid (modulates tissue regeneration)14

The Wou nd Occlusive is formulated for patients with superficial, acute, chronic and post-surgical wounds. These wounds include necrotic and sloughy highly exudative wounds. The Wound Occlusive is a gentle dermatological application to minimise pain once applied to the wound bed. The honey based wound ointment will cause less pain and utilizes the antibacterial strengths of honey (osomosis & peroxide).

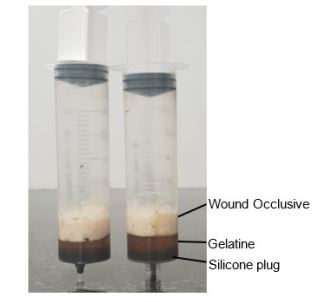

The selection of secondary dressing also plays an important role in the treatment of wounds. The dressing types utilized in the following cases was determined after evaluation of the respective wounds. By means of a fluid affinity test, using 10g of gelatine and 10g of Wound Occlusive, it was determined that ±17.0% of moisture is donated to the wound over a period of 48 hours by die Wound Occlusive, consequently hydration takes place.

The ethical principles for this research were aligned with the declaration of Helsinki. The primary purpose of this research study involving human subjects was to understand the causes, development and effects of wounds and improve preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for safety, effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility, and quality. All subjects willfully participated and signed an indemnity prior to the acquisition of the Wound Occlusive and formulated professional treatment protocols. All medical treatments were conducted by individuals with a medical degree licensed with the Health Professions Council of South Africa or, diploma in advanced dermal aesthetics. All the professional treatments that were performed were done in a controlled environment at the respective practitioners practice or hospital environment. The respective subjects consciously participated in the study and completed an indemnity form prior to the treatment performed. None of the treatments that were performed were invasive or uncomfortable. Subjects were requested to complete a client form to divulge all relevant medical history, allergy, or pregnancies.

Patient A is a 71-year-old male that presented with a severe skin lesion on the forehead. The skin lesion had to be surgically debrided by means of a sloughectomy.

The patient is a non-smoker and appeared generally healthy.

The wound was located on the frontal forehead, and during the first observation it can be stated that there were clear signs of inflammation and lesion discolouration as well as slight edema in the tissue surrounding the lesion. The patient also indicated that the lesion not only caused emotional distress but also that he experienced pain. The Wound Occlusive ointment was applied to the wound immediately after surgery. The wound was kept closed for 5 days. Pos surgery, the treatment protocol followed consisted of cleaning the wound with saline, where after Wound Occlusive was applied to the wound as a thick paste. For this wound a paraffin gauze was applied as a secondary dressing to allow optimal wound granulation. Initially the wound dressing was repeated every 48 h, although after the first two 48 h treatments, the wound was re-evaluated and moved to a 72 h regime.

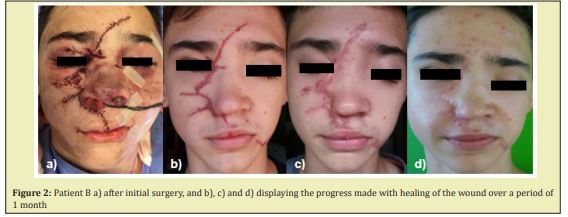

From Figure 1 it can be observed that the size of the wound, cellular migration, differentiation, and proliferation decreased significantly over post-surgery. In addition, it was observed that inflammation and edema in the areas surrounding the wound decreased, this observation was supported by patient feedback. Patient B is a 13 year male that presented with a significant soft tissue injuries in the facial area post suture. The injury was the result of a hyena bite. The injury location ranged from the frontal region though the orbital, infraorbital, and buccal region to the oral region.

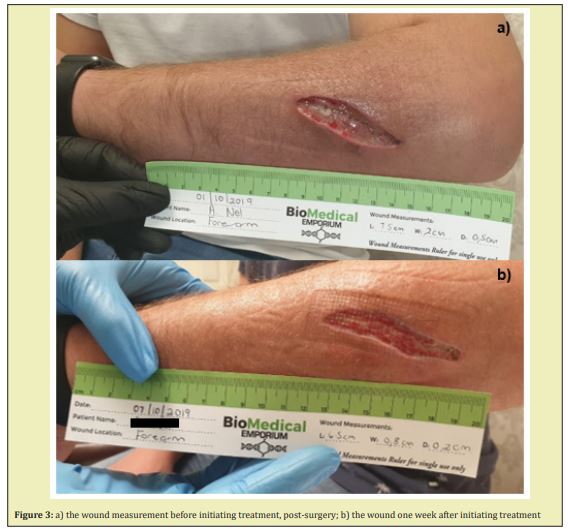

From Figure 2b to Figure 2d it can be observed that the amount of scarring was significantly reduced. Patient C 31-year-old male, presented with a brown recluse spider bite otherwise known a violin spider. The bite occurred approximately 8 day before surgical debriding of the wound was performed and was located on the left antebrachium (forearm). Patient C can be described as generally healthy with no chronic conditions. After surgical debridement, the wound was left open, hence the type of wound can be described as an open post-surgical wound.

When observing Figure 3a – Figure 3b it can be noted that both the length, width and depth of the wound decreased within the period of one week. Additionally, it should be mentioned that the amount of exudate present on the wound bed was markedly lower, and no signs of infection could be noted. Patient D, a 79-year-old male presented with an oncologic posterior lower limb ulcer on the left leg. This patient presented with this chronic state wound for more than 18 months. The patient was encouraged to clean the wound daily with a chlorhexidine solution which can be denoted to the delayed response of optimal healing. Once the patient arrived at the Biomedical Emporium clinic his wound was introduced to the 72-hour protocol of with the application of Wound Occlusive. After the third dressing change it can clearly be observed that the patient wound bed indicated less inflammation and more cellular proliferation was observed by the wound edges.

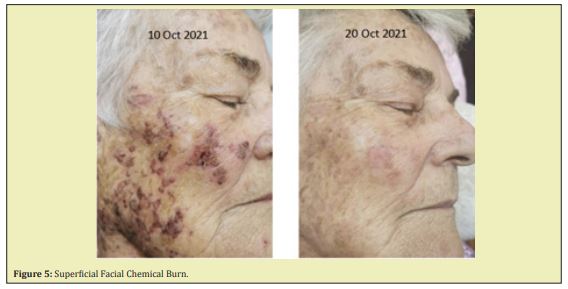

Patient E, A 76-year-old female presented with a superficial facial chemical burn as illustrated in Figure 5. The patient experienced erythema, warmth, oedema, skin discoloration and localised pain. The patient was instructed to apply the Wound Occlusive twice daily after a gentle facial cleansing 10 days. The sensitivity of the skin started to subside after 48 hours and the visible appearance for the facial burns indicated a profound improvement. The Wound Occlusive was applied topically twice daily over the entire facial area. Figure 5 illustrates that the inflammation was reduced as well as the Wound Occlusive adding to provide a moist environment for the skin barrier to retain more moisture and repair efficiently.

Wounds can significantly affect a patient’s quality of life in numerous ways due to pain, odor, decreased mobility, social isolation psychological problems such (i.e. depression and anxiety) and the inability of the patient to perform daily duties and activities.15 These factors places emphasis on the importance of treating wound in a correctly, efficiently, and timeously manner to minimize the effects on other areas of the patient’s life. This objective was achieved in the above-mentioned case studies with the utilization of Wound Occlusive. The ease by which the treatment can be applied could also be seen as a beneficial factor as this might enhance patient compliance. This can be considered an attribute of Wound Occlusive due to the frequency of application (24 - 72 hour) and the ease of application. Additionally, the use of Wound Occlusive in daily wound care practice may pose a solution the increasingly perturbing problem of bacterial resistance toward antibiotics, as honey provides advantageous antibacterial activity against a variety of microorganisms, with no known honey-resistant phenotypes identified up to date.16 It can be concluded from the above-mentioned case studies that Wound Occlusive can be successfully implemented in a variety of wound types.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Vernar T, Bailey T, Smrkolj V. The Wound Healing Process: An Overview of the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1528–1542.

- 2. Shankar M, Ramesh B, Kumar R, et al. Wound healing and it’s importance- a review. Der Pharmacologia Sinica. 2014;1(1):24–30.

- 3. Little S, Menewat S, Worzniak M. Teaching wound care for family medicine residents on a wound care service. Adv Med Educ Prac. 2013;19(4):137–144.

- 4. Guo S, DiPietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010; 89(3):219–229.

- 5. Fagerdahl A. The patient’s conceptions of wound treatment with negative pressure wound therapy. Healthcare. 2014;2:272–281.

- 6. Marshall CD, Hu MS, Leavitt T, et al. Cutaneous scarring: basic science, current. Adv Wound Care. 2016;7(2):29–40.

- 7. Negut I, Grumezescu V, Grumezescu AM. Treatment strategies for infected wounds. Molecules. 2018;23(9):1–23.

- 8. Ghosh C, Sarkar P, Issa R, et al. Alternatives to conventional antibiotics in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27(4):323–338.

- 9. Ubbink D, Westerbos S, Nelson E. A systemic review of topical negative presure therapy for acute and chronic wounds. Br J Surg. 2008;95(6):685.

- 10. Kwakman PHS, Velde AA, Boer L, et al. Two Major medicinal honeys have different mechanisms of bactericidal activity. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17709.

- 11. Minden Birkenmaier BA, Bowlin GL. Honey-based templates in wound healing and tissue engineering. Bioengineering (Basel), 2018;5(46):1–27.

- 12. Kogan S, Sood A, Granick MS. Zinc and wound healing: a review of zinc physiology and clinical applications. Wounds. 2017;29(4):102–106.

- 13. Rhoads DD, Wolcott RD, Percival SL. Biofilms in wounds: management strategies. J Wound Care. 2008;17(11):502–508.

- 14. Litwiniuk M, Krejner A, Grzela T. Hyaluronic Acid in inflammation and tissue regeneration. Wounds. 2016;28(3):78–88.

- 15. Situm M, Kolić M, Spoljar S. Quaaality of life and psychological aspects in patients with chronic leg ulcer. Acta Med Croatica. 2016;70(1):61–63.

- 16. Maddocks SE, Jenkins RE. Honey: a sweet solution to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance?. Future Microbiol. 2013;8(11):1419–1429.