Background: Good mental health and well-being are essential for fulfillment, productivity, and resilience. Mental disorders cause high levels of disability and economic impact worldwide. Vulnerable groups at significantly higher risk include youth and First Nations people. As the demand for mental health support and services increases, there is an urgent need to expand access to culturally appropriate quality mental health services (particularly for young people) and to promote self-care through integration of mobile health technologies.

Objectives: This paper describes a protocol to evaluate implementation of the AIMhi for Youth support package into youth wellbeing services in urban, rural, and remote Northern Territory and South Australia. Codesign workshops will tailor the resources to these and other locations. The AIMhi-Y support package will be implemented as an innovative approach to suicide prevention through three years of codesign, training, implementation support and dissemination.

Methods: Implementation is guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) incorporating the recent CFIR Outcomes Addendum and including strategies from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change. The protocol incorporates best practice principles in codesign and First Nations research. It builds on a decade of foundational work of the Stay Strong program implementing digital mental health resources in primary care and specialist settings. Implementation and related outcomes will be evaluated from each participant perspective (user, service provider, decision maker, First Nations people with lived experience and cultural consultants) using surveys and small group discussions.

Intervention: AIMhi for Youth is a culturally responsive digital mental health solution codesigned with First Nations leaders and young people. Delivered via mobile device it is a gamified app supporting skills development in mental health literacy, emotional regulation, help seeking and goal setting. The app provides a structured intervention which complements existing services and addresses key risk factors for suicide and compromised mental health. The package includes training workshops and supplementary multimedia resources. Support resources will be hosted on a tailored website creating a seamless accessible ecosystem for users.

Discussion: At the time of publication, 514 young people and 363 individual service providers have used the app, and 11 services have engaged in implementation planning discussions. Through our implementation evaluation we will identify why the AIMhi-Y package was implemented successfully in some contexts and not in others and will have an evidence-based strategy for successfully engaging First Nations young people and services in digital mental health solutions. This will inform further AIMhi-Y dissemination and provide a guide for implementation of other innovations in similar contexts.

Conclusion: This study prospectively plans, monitors, and evaluates implementation through use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. This threefold approach potentially strengthens the design and enhances likelihood of implementation success. The emphasis on Indigenist research principles, and the addition of measuring outcomes including reach, impact, adoption, implementation, and sustainment, has potential to contribute to conceptual development and clarification of implementation approaches in First Nations communities.

Keywords: AIMhi, Mental health, CFIR, Young people

Good mental health and well-being are essential for fulfillment, productivity, and resilience. Mental illness is a crucial issue internationally. Mental disorders cause high levels of disability and economic impact worldwide with vulnerable groups such as youth and First Nations people at significantly higher risk. Most First Nations populations in colonised countries experience poor health outcomes relative to their non-First Nations counterparts.1 These disparities are often linked to historical, economic, and social factors including colonial policies where dominant societal views shaped health systems and models of care.2 The World Health Organisation (WHO) action plan identifies an urgent need to expand access to culturally appropriate quality mental health services and to promote self-care through integration of mobile health technologies.3 In addition, the WHO encourages the involvement of First Nations peoples and communities in policies and programs, and recognition and promotion of cultural heritage and traditional knowledge. Prioritising the involvement, collaboration and empowerment of First Nations communities and leadership is deemed critical to successful transformation of healthcare.4 In Australia, the National Mental Health Workforce Strategy 2022-2032 echoes WHO recommendations. It identifies need for services which address the diverse needs of consumers and carers, and priority populations, and improve access to digital technology.5

Individual and collective resilience for Australia’s First Nations people is supported by a positive and strong sense of cultural identity, knowledge of traditional cultural beliefs and values, participation in cultural activities and practices, and engagement in cultural gatherings.6 This power of connection to people, country, and spirit is central to the their enduring strength.7 However, colonisation led to disconnection between people, families, communities, and country. Many First Nations communities were historically displaced from their traditional lands. Forced segregation on missions and reserves disrupted traditional relationships,8 and many First Nations families and communities in contemporary Australia face immense challenges. The construct of historical trauma describes the disproportionately high rates of psychological distress and health disparities among First Nations peoples.9

Despite high rates of distress, few mental health resources are specifically designed to meet the needs of First Nations peoples and few tools have been successfully implemented and rigorously evaluated. Since 2003, the Menzies Stay Strong Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative (AIMhi) has developed and evaluated assessment, psychoeducation, and care-planning resources with First Nations people.10-12 The AIMhi Stay Strong Plan is a key resource providing the theoretical underpinning and evidence-base for the Stay Strong concept of practice. This ‘low-intensity’ cognitive behavioural treatment differs from established approaches by using a holistic approach with pictorial prompts.11,13 The therapy adopts an empowering, person-centred, stance which acknowledges Indigenous cultural and family values, and promotes trauma informed care and self-management.14 It was evaluated in one of the first clinical trials assessing mental health interventions in remote Australia, with follow up studies further confirming acceptability and effectiveness.10,12,15-17 The Stay Strong plan has been transformed to digital format (the Stay Strong App), with additional evidence of acceptability and effectiveness.18,41 The AIMhi for Youth (AIMhi-Y) app support package integrates key elements of the Stay Strong concept of practice in resources specifically aimed at young people.

Although resilient, First Nations young people are a vulnerable group for whom help-seeking is hindered by stigma, distance, cost, and cultural and linguistic differences. Strong connections with land, family and community promote healthy development for First Nations young people.19,20 Programs which improve young people’s resilience through bolstering cultural identity, integrating First Nations worldviews and promoting help seeking can improve mental health and influence the high rates of youth suicide within First Nations communities.10,21-23 Digital mental health solutions offer flexible access to evidence-based, non-stigmatising, low-cost treatment, and early intervention. Resource design which recognises the diversity among First Nations peoples, past and present24 can take advantage of the rapidly growing use and acceptance of technologies among First Nations youth.25 This project harnesses the potential of culturally responsive digital mental health solutions to provide accessible, effective mental health support for First Nations young people.

The AIMhi-Y app for smartphone was developed through five years of foundational work of codesign and feasibility testing.26-28 It is a brief, supported, and self-guided intervention for young people 12-25 years which embeds a Stay Strong plan, guidance from elders, and builds connection with country and language. It integrates cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness-based activities and promotes conscious choice and a sense of control over important life decisions, consistent with trauma-informed care. It addresses wellbeing concerns through a gamified and engaging approach to skills development in mental health literacy, emotional regulation, help seeking and goal setting. Feasibility testing with First Nations young people attending Darwin youth wellbeing services showed clinically significant improvement in distress and depression scores and high app approval ratings.28 We will adopt a staged approach to implementation of the AIMhi-Y app for use by school and community-based services. Codesign workshops will tailor the app resources to different locations. The app provides a structured intervention which complements existing services and addresses key risk factors for suicide and compromised mental health. The package includes training workshops and supplementary multimedia resources. Support resources will be hosted on a tailored website creating a seamless accessible ecosystem for users. As a culturally responsive, low-intensity digital mental health tool, the AIMhi-Y app and support package can provide effective, accessible mental health care with comprehensive reach.27 Importantly, the app addresses key risk factors for youth suicide: compromised mental health, cultural dislocation, and limited access to services.

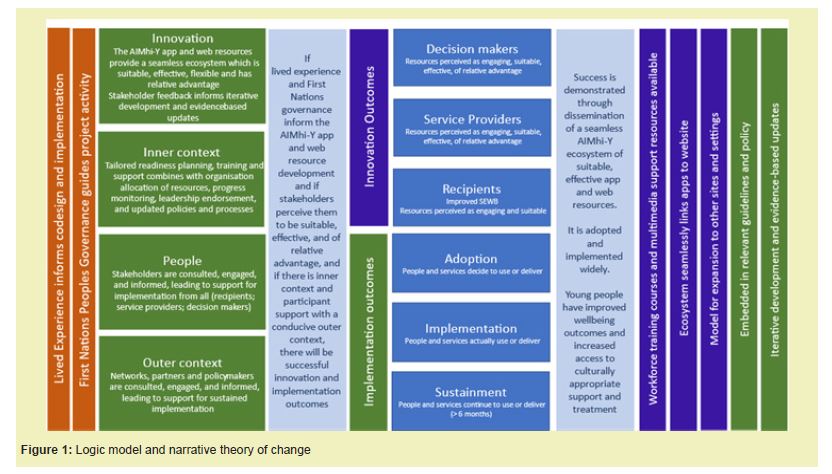

The aim of this protocol is to prospectively design a strategy for implementation and evaluation of the AIMhi-Y app wellbeing support package within services and schools. The strategy uses the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to identify contextual factors, tailor the innovation and the implementation strategies throughout, and evaluate outcomes from the perspectives of both the innovation and the implementation. Key objectives are to ensure voices of First Nations participants are advanced through governance and codesign, and to examine process and outcome measures guided by a logic model and narrative theory of change developed using the CFIR Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

We use the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) incorporating the recent CFIR Outcomes Addendum as the determinant theoretical framework for this study.29 Use of pre-specified constructs provides a window for understanding and influencing the multiple variables that influence implementation success and helps generalise the findings. Evaluating the implementation of complex interventions helps to identify the reasons why interventions work in some contexts and not in others and can then inform adaptions for specific contexts and systems. Using a recognised theoretical approach to guide implementation also facilitates the scientific reporting of the rationale and theory underpinning the implementation strategy used in a study.30

The CFIR includes 39 constructs (i.e., determinants), organized into five domains: Innovation Characteristics (e.g. stakeholders’ perceptions about the relative advantage of implementing the intervention), Outer Setting (e.g., external policy and incentives), Inner Setting (e.g., organizational culture, the extent to which leaders are engaged), Characteristics of Individuals Involved (e.g., knowledge and beliefs about the intervention), and Implementation Process (e.g., planning and engaging key stakeholders).

The CFIR Outcomes Addendum addresses both implementation and innovation outcomes allowing assessment of reach and impact of the study.29 We also include strategies from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC).31 Using these combined CFIR tools thus allows comprehensive exploration of barriers and facilitators, provides expert strategies to guide implementation, and measures implementation outcomes.

The study and related protocol build on ten years of experience in implementation of digital mental health in similar settings. This earlier work found that the integrated-Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework provides a useful determinant framework for deepening understanding of how different factors impede or facilitate electronic mental health adoption in this setting.32,33 The framework posited that successful implementation is achieved through a facilitation process (Facilitation) which assesses and aligns knowledge regarding the innovation to be implemented (Innovation), the individuals and/or teams involved in the process (Recipients), and the settings in which the innovation is to be implemented (Context).34 Facilitation is recognized as the central ingredient of this approach.35 Our key findings have been that organisational readiness consultations between external and internal facilitation teams which review resources, protocols and processes enhanced likelihood of implementation success.32,33 Merging that understanding with prospective planning and outcome measurement, and shifting to the CFIR framework, are key differences in the approach we have adopted in this study. We found it useful, however, to maintain the concept of the internal and external facilitation team. This extends the definition of participants in the implementation journey to those who are supporting activities within the organisation and the support provided externally by the study team.

Design

The CFIR allows for flexibility and tailoring the framework to the study context. We chose to focus on the constructs from the CFIR that are most relevant for this study setting to guide development of the evaluation tools (Innovation and Inner setting), although individuals and outer setting were also addressed to some extent Table 1. Qualitative and quantitative data are collected from young people, decision makers, service providers, reference group and advisory group members via semi structured interviews, surveys, observation, and field notes. Additional quantitative data includes web and app analytics and key process variables. Data collection tools were designed based on our earlier findings, literature review and the CFIR framework, and were then tailored to each participant group with advice from First Nations advisory groups, cultural consultants, and research team members.

Logic model

Our logic model accompanied by a narrative theory of change informs the evaluation Figure 1. It is adapted from existing logic model frameworks and informed by CFIR and Indigenist research principles. The model incorporates CFIR outcomes including measures of reach and impact.

Innovation

The AIMhi-Y app provides a structured intervention which complements existing services. Service providers conduct a supportive 30-minute session with the app support package to introduce and orient young people. Young people are encouraged to access the app at least weekly. The app includes easily accessible help and support contact information. It is designed to be both service supported and user driven. Support resources will be hosted on a tailored website designed from the user journey perspectives of young people (‘young mob’), adults (‘mob’) and ‘workers’.

Study settings

The AIMhi-Y app and related support resources were designed in The Northern Territory of Australia. Codesign workshops will tailor the resources to South Australia before implementation commencement. We will follow this sequence for implementation in other locations as well, however as the app is now released publicly many locations have chosen to already download the Northern Territory version. Thus far, x services and providers and x young people across the country have downloaded this first version of the AIMhi-Y app.

First Nations governance and lived experience

The Stay Strong team has been led by a local Larrakia First Nations consultant and guided by local First Nations reference groups and First Nations researchers, Elders, and leaders since inception in 2003. For ten years it has also been advised by a digital mental health Expert Reference Group and more recently an Expert Safety and Quality Group. In this study the research team has expanded to include First Nations people living and working in South Australia. An overarching Project Advisory Group drawn from experts in First Nations youth wellbeing provides guidance at quarterly meetings and key decision points, and local Youth Reference Groups inform codesign of local resources. We used the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander QAT) to guide the study and ensure a user-centred design approach.36 The tool draws on several guidelines which outline best practice approaches to engaging First Nations people in research.37,38 This 14 – item tool aims to increase the quality and transparency of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research practice and reporting.

Implementation stages

There are 4 stages of implementation in this project. All stages include evaluation and feedback.

- 1. Pre implementation activities

- 2. Implementation: Readiness for change planning, complete digital mental health index and action plan

- 3. Implementation: Training and support, continued readiness planning and action plan review

- 4. Sustainment: Support implementation, engage widely to ensure workforce training and policy impact

Our experience has been that different services and service providers take different journeys through implementation stages. By releasing the app publicly rather than on a recruited service, case by case basis, we made a pragmatic decision to potentially strengthen reach whilst recognising that implementation processes would have greater variation as a result. App and web analytics will allow some insight into the success of adoption and implementation within services that do not directly engage with our implementation support.

Pre-implementation activities

The AIMhi team has existing relationships with a range of services supporting the wellbeing of young people. Services are invited to participate through e-newsletters, social media, online and face to face promotional activities. Youth wellbeing services in Darwin, Alice Springs and Adelaide are recruited through established networks. Pre-implementation strategies include engagement and awareness raising prior to readiness for change discussions with service leaders. Pre-implementation discussions cover detail of the innovation, readiness planning and implementation activities. Local enablers and barriers are explored.

Pre-implementation activities – South Australia

This phase differs in South Australia given the great diversity among First Nations peoples, past and present: different languages and cultures, different lands, histories, economies, politics, and relationships with other groups (26). In South Australia, codesign workshops will tailor the resources to local language and culture before implementation through six phases of codesign.

- 1. Consultation and permissions and expressions of interest

- 2. Youth Reference Group and Cultural Advisor meetings

- 3. Codesign workshops with young people and cultural consultants

- 4. Coproduction of videos, local characters, stories, and games

- 5. Local characters, stories, games, videos are incorporated into the AIMhi-Y package

- 6. App and Web resources are released following user testing

The AIMhi team has relationships with a range of services supporting the wellbeing of young people in South Australia and Stages one to three have progressed well. Comprehensive consultation led to establishing and nurturing relationships with community leaders, elders, youth, and knowledge holders and engagement of key members of the local Kaurna community and Elders. The Kaurna language (Kaurna Warra) is the original language of Adelaide and the Adelaide Plains, South Australia. Consultation and permission from Kaurna Elders supported conduct of eight workshops with school aged young people. We sought to integrate First Nations ways of knowing, being, and doing through respect for and inclusion of First Nations Knowledge in workshop delivery, data collection, and data analysis. Workshop design was led by the Kaurna knowledge holders and informed by tools supporting insight into app development. Participants were encouraged to yarn about their experiences with specific prompts drawn from the Stay Strong concept of practice. Following the initial data analysis in South Australia and NT, the SA team began crafting prospective narratives tailored to young men and young women. Subsequently, a thorough discussion encompassing the data, findings, and analysis was undertaken in consultation with Kaurna cultural consultant. A Further youth codesign and reference group workshop reviewed a selection of potential narratives and accompanying activities, to check the narrative' accuracy and craft visual representations of characters and the South Australian landscape. The workshop led into a stakeholder luncheon and afternoon with young participants and Elders dedicated to discussion, data analysis, recognition of achievements, and approaches to incorporation of local language. The process included local First Nations young people, cultural consultants, Elders, and the Kaurna Yerta Aboriginal Corporation. Stages four to six are underway after which implementation activities will commence.

Implementation: Readiness for change planning

We know from our foundational work implementing digital mental health tools with primary care services that readiness to change discussions prior to training of service providers are pivotal. As a result, we developed a three-phase implementation program of pre-training consultations, training, and follow-up support32 and developed a tool to support readiness to change discussions. The 7-item digital mental health-Index measurement tool is specific to digital mental health implementation and is intended for use as both a discussion and evaluation tool. The tool is informed by the integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation (i-PARIHS) theoretical framework,34 the Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment (ORCA), the Checklist to Assess Organizational Readiness (CARI), and our research findings. It has been updated to an x-item tool incorporating concepts drawn from the CFIR framework and ERIC strategies, and further learnings from our implementation research.39,40 The tool uncovers enablers and barriers to implementation and leads to a confirmed action list for follow up. This phase also includes consultation and awareness raising, promotional sessions and information from external and internal perspectives via e-newsletter and organisation network communications. Specific organisational actions include consultation with consumers, resource allocation, information system review, and policy review. Barriers are addressed through targeted use of ERIC strategies. This phase continues throughout implementation.

Implementation: Tailored training and support

In this phase, training workshops introduce the app and support package and the Stay Strong concept of practice. Services and service providers have options to attend interactive workshops of varied length from one hour introduction sessions to two-day workshops, inclusive of a train the trainer option. Format and length of training workshops is tailored to maximise attendance. Training support materials are introduced and distributed including training manual and supplementary training materials.

Implementation: Codesign of additional support resources

This phase involves use of best practice principles in both the process of participatory design, and engagement of First Nations people in research, to develop additional multimedia resources tailored to different implementation sites.26,36 Youth reference groups are established in each site. Workshops are facilitated by local implementation support team members including senior and younger First Nations project officers and local cultural consultants. Co-design workshops use generative methods to further refine and design app support package attributes.

Sustainment: Follow up support

This phase includes site visits and face to face or online follow up. Follow up encourages ERIC strategies such as further leadership promotion and innovation endorsement, and addresses enablers and barriers. It also extends the engagement to other institutions, educational courses, and policy settings, seeking to embed the intervention in best practice guidelines and workforce training.

Data collection

Qualitative and quantitative data are collected from stakeholders via semi structured interviews, surveys, observation, and field notes guides. Additional quantitative data include web and app analytics and key process variables. Data collection methods are tailored to implementation domain, activity, and stakeholder Table 1.

We will use a mixed-method approach, using both quantitative and qualitative methods, to monitor and assess implementation success. Descriptive statistics will be calculated for services recruited in the study and relevant process variables. The study team will thematically analyse qualitative data with interpretation guided by First Nations research team members and consultants. NVivo software will aid in the coding and organisation of themes.42

The study has received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of NT Health and Menzies School of Health Research including the Aboriginal Ethics Subcommittee (HREC2022-4347); the NT Department of Education (ref 20938); Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (AHREC) of South Australia (Ref 04-22-995) and the SA Department of Education.

At the time of publication, 514 young people and 363 individual service providers have used the app, and 11 services have engaged in implementation planning discussions. Through our implementation evaluation we will identify why the AIMhi-Y package was implemented successfully in some contexts and not in others and will have an evidence-based strategy for successfully engaging First Nations young people and services in digital mental health solutions. This will inform further AIMhi-Y dissemination and provide a guide for implementation of other innovations in similar contexts.

This study prospectively plans, monitors, and evaluates implementation through use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. This threefold approach potentially strengthens the design and enhances likelihood of implantation success. The emphasis on Indigenist research principles, and the addition of measuring outcomes including reach, impact, adoption, implementation, and sustainment, has potential to contribute to conceptual development and clarification of implementation approaches in First Nations communities.

The authors would like to thank the members of the AIMhi-Y Project Advisory Group, and the Stay Strong Expert Quality Group for their contributions to this project.

This project was funded by a Commonwealth Department of Health National Suicide Prevention Leadership grant with grant number 4-HC7HOI3.

Regarding the publication of this article, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- 1. Barnabe C. Towards attainment of Indigenous health through empowerment: resetting health systems, services and provider approaches. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(2):e004052.

- 2. Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65-75.

- 3. World Health Organization. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013-2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; Geneva: WHO. 2021.

- 4. World Health Organisation. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. 2012.

- 5. Department of Health and Aged Care. National Mental Health Workforce Strategy 2022-2032. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. 2022.

- 6. Usher K, Jackson D, Walker R, et al. Indigenous Resilience in Australia: A Scoping Review Using a Reflective Decolonizing Collective Dialogue. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9.

- 7. Edwige V, Gray P. Significance of Culture to Wellbeing, Healing and Rehabilitation. New South Wales: Australian Bar Association. 2021.

- 8. Price Robertson R, McDonald M. Working with Indigenous children, families, and communities Lessons from practice Melbourne, Australia. Australian Institute of Family Studies. 2011.

- 9. Gone JP, Hartmann WE, Pomerville A, et al. The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review. American Psychologist. 2019;74(1):20-35.

- 10. Nagel T, Robinson G, Condon J, et al. Approach to treatment of mental illness and substance dependence in remote Indigenous communities: Results of a mixed methods study. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2009;17(4):174-182.

- 11. Nagel T, Thompson C. AIMHI NT 'Mental Health Story Teller Mob: Developing stories in mental health. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health (AeJAMH). 2007;6(2):119-124.

- 12. Nagel T, Thompson C. Motivational Care Planning:Self management in Indigenous mental health. Australian Family Physician. 2008;37(12):996-1001.

- 13. Laliberte A, Nagel T, Hasswell Elkins M. Low intensity CBT for Indigenous consumers: Creative solutions for culturally appropriate mental health care. In: Bennett-Levy JRD, Farrand P, Christensen H, Griffiths K, Kavanagh D, Klein B, et al., editors. Low Intensity CBT Interventions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2010.

- 14. Nagel T, Robinson G, Condon J, et al. An Approach to Treating Depressive and Psychotic Illness in Indigenous Communities. Australian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2008;14(1):17-21.

- 15. Hinton R, Nagel T. Evaluation of a culturally adapted training in Indigenous mental health and wellbeing for the alcohol and other drug workforce. ISRN Public Health [Internet]. 2012:p.6.

- 16. Nagel T, Thompson C, Spencer N, et al. Two way approaches to Indigenous mental health training: Brief training in brief interventions. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health (AeJAMH). 2009;8(2):135-41.

- 17. Jayaraj R, Thomas M, Thompson V, et al. Effectiveness of Stay Strong Treatment of Alcohol Related Trauma: Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial. Int J Nurs Health Care Res. 2024;7.

- 18. Dingwall KM, Sweet M, Cass A, et al. Effectiveness of Wellbeing Intervention for Chronic Kidney Disease (WICKD): results of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Nephrology. 2021;22(136).

- 19. MacLean S, Ritte R, Thorpe A, et al. Health and wellbeing outcomes of programs for Indigenous Australians that include strategies to enable the expression of cultural identities: a systematic review. Australian journal of primary health. 2017;23(4):309-318.

- 20. Purdie N, Dudgeon P, Walker R, editors. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Australian Capital Territory: Commonwealth of Australia. 2010.

- 21. Campbell A, Balaratnasingam S, McHugh C, et al. Chapman M. Alarming increase of suicide in a remote Indigenous Australian population: an audit of data from 2005 to 2014. World psychiatry. 2016;15(3):296-297.

- 22. Pearson S, Hyde C. Influences on adolescent help-seeking for mental health problems. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools. 2021;31(1):110-121.

- 23. Dudgeon P, Kelly K. Contextual factors for research on psychological therapies for Aboriginal Australians. Australian Psychologist. 2014;49(1):8-13.

- 24. Watts E, Carlson G. Practical strategies for working with indigenous people living in Queensland, Australia. Occupational Therapy International. 2002;9(4):277-293.

- 25. Povey J, Mills PPJR, Dingwall KM, et al. Acceptability of mental health apps for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2016;18(3):e65.

- 26. Povey J, Sweet M, Nagel T, et al. Determining Priorities in the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for Youth App Second Phase Participatory Design Project: Qualitative Study and Narrative Literature Review. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(2):e28342.

- 27. Povey J, Sweet M, Nagel T, et al. Drafting the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for Youth (AIMhi-Y) App: Results of a formative mixed methods study. Internet Interv. 2020;21:100318.

- 28. Dingwall KM, Povey J, Sweet M, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for Youth App: Nonrandomized Pilot With First Nations Young People. JMIR Hum Factors. 2023;10:e40111.

- 29. Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, et al.Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): the CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implementation Sci. 2022;17:7.

- 30. Guyatt S, Ferguson M, Beckmann M, et al. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to design and implement a perinatal education program in a large maternity hospital. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21(1):1077.

- 31. Powell B, Waltz T, Chinman M, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):21.

- 32. Raphiphatthana B, Sweet M, Puszka S, et al. Evaluation of a three-phase implementation program in enhancing e-mental health adoption within Indigenous primary healthcare organisations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):576.

- 33. Raphiphatthana B, Sweet M, Puszka S, et al. Evaluation of Electronic Mental Health Implementation in Northern Territory Services Using the Integrated "Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services" Framework: Qualitative Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(5):e14835.

- 34. Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science. 2016;11(1):33.

- 35. Hunter SC, Kim B, Mudge A, et al. Experiences of using the i-PARIHS framework: a co-designed case study of four multi-site implementation projects. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20(1):573.

- 36. Harfield S, Pearson O, Morey K, et al. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC medical research methodology. 2020;20(1):79.

- 37. Anderson W. 2007 National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Intern Med J. 2011;41(7):581-582.

- 38. National Ethics Advisory Committee. National Ethical Standards for Health and Disability Research and Quality Improvement. Wellington, NZ: Minsitry of Health. 2019.

- 39. Helfrich CD, Li YF, Sharp ND, et al. Organizational readiness to change assessment (ORCA): Development of an instrument based on the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implementation Science. 2009;4(1):38.

- 40. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Pre-implementation organizational readiness assessment tool Hamilton, ON: McMaster University. 2014.

- 41. Dingwall KM, Puszka S, Sweet M, et al. Like drawing into sand”: Acceptability, feasibility and appropriateness of a new e-mental health resource for service providers working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Psychologist. 2015;50(1):60-69.

- 42. Lumivero. NVivo (Version 14). 2023.