This case study depicts a 66-year-old retired man with bipolar disorder, exhibiting the loss of cognitive functions (specially working memory), in a cognitive dysfunction process. Upon the medical exams and Neuropsychological evaluation results, an intervention programme was created, based on exercises of perception, attention, memory, language, among others, to help the patient to preserve the remaining cognitive functions. However, the analyst learned with the patient, picked up his cues and changed the intervention method. After seven months of psychoanalysis support therapy, with the free association method, the patient felt recognized, and showed results from the impact of his emotions’ resonance inside the analyst in the “here and now” experience. Gradually he moved from the schizo-paranoid position into the depressive one, reinforcing different parts of the self in his identity process. At the same time, he improved his executive functions showing an organized and planning thought and, above all, he realised the way he wanted to be remembered which helped him to build better relationships and to find more significance in the forgetting experience.

Cognitive dysfunction, Psychoanalysis support therapy, Learning with patient, Empathy, Resonance

The growing concern about longevity, to add (more) years in life, leads concern in science about the high-risk of physical and mental impairments in ageing. In this sense, there is a need to preserve the psychic life of the human being, in (the more and more common) longer years. This case study highlights the importance of learning with the patient, and rely on his insight ability, although with declining cognitive skills, picking up the cues in every phase of evaluation and intervention.

The patient is a 66-year-old retired man, after suffering a stroke episode 10 years ago, a homozygous twin (the eldest two from a fraternity of five), with high level education (attended to the 3rd year in médicine), in a long-term marriage (32 years without children), and has a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. He sought treatment in our clinic (eight years ago), complaining about dizziness and trembling symptoms, which disturbed his painting activity, and made him feel anxious and angry, especially when the results were hurting his pride. Painting was an activity that pleased him very much that he discovered after his retirement. From his perspective, dizziness and trembling symptoms were related to medication side effects. However, his wife recently referred manic episodes, lack of sense of reality sense, difficulties in focusing his attention and remembering small things. The lack of movement control leads him to face bigger problems in his daily life, such as driving or even showering or shaving. He was angry with the prescription of Abilify (typically prescribed in the bipolar disorder treatment), as he just asked for an anti-depressive medication.

Following the instruction of the Psychiatrist, in order to screen for frontal executive function difficulties, the patient was submitted to imaging exams, such as Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan, detailing 3 dimensional images of the inside of the body.

Meanwhile, the Psychiatrist asked for screening his cognitive functions, and the patient also submitted to a Neuropsychological exam, consisting in 12 sections: 1- Language, 2- Orientation, 3- Praxis[1], 4- Gnosis[2], 5- Attention, 6- Conceptual Organization, 7- Memory, 8- Mental Calculation, 9- Visual Constructive Ability, 10- Planning and Execution Action, 11- Visual Hemineglect[3]Screening, 12- Humour and Behaviour During the Exam and Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure[4], a drawing reproduction in two parts: copy by freehand (recognition) and then drawing from memory (recall).

[1] Praxis are acquired motor skills (organized movements) that are carried out to achieve an objective.

[2] Gnosis is the ability that the brain has to recognize, through our senses, previously acquired information, such as objects, people, places, etc.

[3] Hemineglect is the inability to answer to visual stimulus (visual, auditory and tactile).

[4] Rey- Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, was first proposed by Swiss Psychologist André Rey and further standardized by Paul.Alexandre Osterrieth in 1944. It is frequently used to assess any secondary effect of brain injury in neurological patients

The PET results showed frontotemporal dementia that affected the centre of decision of the brain. The neuro-psychological exam showed positive results in Praxis, Gnosis, Attention and Visual Construction Ability sections, such as drawing a “flower” and a “house”. However, there were strong difficulties in the following sections:

In the Language section (understanding simple and repetitive orders), especially related to handedness orders. When he heard, e.g., “Put your right hand on the left ear”, he used the left hand, instead, to touch his left ear.

In a qualitative approach, the patient used free association, probably as a self-defence mechanism to show remaining abilities. For instance, the words “Pen” and “Cat” weren’t correctly repeated as he was asked. “Brush” (the most useful object to help him paint)[5] was referred after “Pen”, and “Sweety” (the name of his female cat) after “Cat”. The words “Pencil” and “Brush” do come easily, but they are semantically different. In a metaphorical way, they are used to show meaningful information based on his experience.In the Self Orientation section, the patient revealed lack of auto psychic orientation, as he wasn’t sure about his age (he thought he was about 83 or 84 years-old). Perhaps he was, subjectively, feeling the weight of the years. He could not say in which day, week, month or season he was.

In the Conceptual Organization section, he was not able to interpret any of the Portuguese proverbs: neither analysing, nor abstracting, nor applying them to daily life situations, as Stub & Black (cited by Brunddge, B. Steely (1996)) suggest. The patient just repeated the statements. In the proverb, e.g., “When the sun rises it´s for all [6] he repeated the statement at first and afterwards he highlighted the negative consequences (if it only rises for some) for the ones that end up lonely and homeless. In the Raven Progressive Matrices[7] test (RPM), the outcome was below the average. According to his high education level, one should expect a higher value. The patient revealed lack of mental ability and the failures were related to an anchor effect, as it seemed he was looking for support.

In the Memory (working memory) section, the patient got an under average value and he used, once again, free association as a self-defence mechanism, to highlight his skills and achievements. When he associated, for instance, the word “Clothing” to “Uniform”, he recalled several episodic memories of his military service and from his last job, as medical information manager. There were affective issues related to events. The word “Flower” (the name of his female dog) enabled him to talk about the loss of some relatives, showing emotional lability and easily crying.

In the Mental Calculation section, he succeeded doing an addition operation, although he showed many difficulties, solving a subtraction operation. At the very beginning he asked for a sheet of paper, and used finger counting procedure, without any success. At this time, he showed strong anxiety and despair.

In the Planning and Action Execution section, the patient couldn´t recognize and criticize the absurd sentences. He used free association, instead, based on his affective experiences to jump out of the situation. Once again, he showed anxiety and finished the task, recalling a negative episodic memory related to his twin brother, who suffered from a brain trauma.

In the Visual Hemineglect screening section, Clock Drawing Test[8] (CDT), he was not able to follow the instructions (“Draw a clock with all the numbers on the dial and place the hands at 2 hours and 45 minutes”). He invested in other details, instead, drawing a wristwatch with bracelet and buckle. The hand points had the same size and in the way they were drawn, it could be 1:15 or 3:05. In the bottom part of the circle, he drew the number 16. According to Agrell Bert and Dehljn Ove, only one quarter of the patients with a stroke episode would reveal neglect, when the number 16 is drawn. In fact, the patient had shared that he had a stroke, right before his retirement.

In the Humour and Behaviour section, the patient revealed strong anxiety, most of the time, an expression of fear (eyebrows and lower eyelids pulled up and mouth stretched and drawn back, exposing his teeth), high speeding breath and emotional lability (easily crying), especially when he recalled episodic memories related to the loss of his mother. The only time he showed some pleasure and satisfaction was when he drew a “flower” and a “house” in the visual constructive ability or used free association to share some episodic memories.

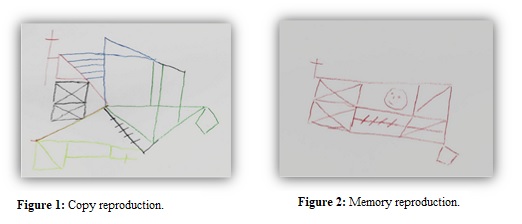

In Rey Complex Figure, the copy reproduction (the image on the left side) revealed difficulties related to visual motor control and graphic apprehension. The lack of the central armour might be interpreted as an inability to contain anxiety.

As the patient drew the image inside of the central armour, the reproduction by memory (on the right side) showed some evolution on the graphic quality. The initial circle appeared to me like an human face, turned to the left side, and expressing a shy smile. Another noteworthy detail is the double rectangle with an “X” inscribed, at the left side of the sheet (showed up in the copy and in the memory reproduction as well), and might be interpreted as an image reflected in a mirror, that seemed to be an attempt to establish an affective connection.

The intervention began with socio-cognitive stimulation sessions in order to maintain the patient’s conceptual organization skills. The materials were prepared according to his interests about art, geography, music and history. Although he had been asked, many times, about what he would like to do most (in our sessions), he showed a tendency to adopt a passive attitude (dependency). Nevertheless, the more the therapeutic relationship was developed, the more the patient felt recognized. Responding to his cues and to his real needs, the intervention method progressed (one month later) into a different direction, in a compass demand, into psychoanalysis support therapy.

[5] In portuguese language the words “caneta” and “pincel”, respectively, aren’t neither homophones, nor homonyms, nor homographs.

[6]This proverb has been used in several romances of José Saramago, a Portuguese famous writer who was awarded the Nobel prize in literature in 1998.

[7] Raven Progressive Matrices were originally designed by John C. Raven in the 1930 to measure educative ability, or the ability to extract and understand information from a complex situation.

[8] The clock-drawing test is used for screening cognitive impairment as a measure of spatial dysfunction and neglect.

The patient brought his own meaningful materials to the sessions: several old photos that helped him remember the most meaningful losses, enabling him to show his sadness (staying in touch with sadness) and helping him achieve the mourning process (which was far from being concluded).

The female dog’s photo, named Flor (Flower in English) was the link to help him talk about his most significant losses. It was easier to speak about Flor and share how much he regretted its death.

Then, looking at the old family house photo (which was sold after his mother’s death), he said:

- “I didn´t return anymore to my childhood town, due to the heartbreak I felt, when I realized the family house had been sold”.

The photos of his mother helped him to remember the most painful loss. Although she passed away 40 years ago (due to a severe cancer) he cried and blamed himself for not having found the appropriate medications to treat her oncological disease. He also regretted he did not use the time to study medicine, but used it, instead, to have fun with his peers.

In that session, he decided to stick some photos in an album, following his own chronological sequence, and to write some meaningful sentences about them.

The images of the photos helped him to get closer to his emotions. According to Lifton & Olson (2018), “seeing” and “recognizing” are related to the fact that it is possible to create meaning in the psychic structure. Through the therapeutic relationship, the patient felt understood, validated in his emotions, especially in sadness (the hardest emotion for the patient to withstand).

He brought a book related to Egyptian culture and a black folder with several photos inside (as if it was an old treasure) and began talking enthusiastically about the most relevant mistress he had, laughing about the times he had to run away in order not to be caught by her husband.

- “Sometimes there is a need to run away from feelings such as sadness”, I said.

As Lifton & Olson (2018) said “... death in psychological influence is due to the importance of symbolization in mental activity”. After getting close to sadness, he was able to stay more peaceful with his emotions. In this way, he showed the ability to get close to sense of symbolic immortality.

The wooden box, full of old coins, was the link to connect him to one of his nephews (the closest one, since he did not have children), who he chose to leave his belongings. This was the motivation to help him manage death anxiety. In this way, he could relate to what comes before him and all that follows after him. This is a symbolized way that enables him to go on with his life, without denying the reality of death.

Thinking about the origin of coins, he remembered the last time he travelled to Paris to visit his nephews (the children of his twin brother). Then he decided to leave a coat of arms ring (the one he had on his finger) to the closest nephew, who was very fond of monarchy.

- “Leaving things we appreciate most, with the beloved ones, can be a way to keep a part of us alive ”, I said.

Although he answered positively, he immediately changed the subject, as he was not ready to experience that feeling. At that time, it was not possible to keep on talking about his finitude/death.

He found some more photos of his mother and his siblings (when they were children) but his father wasn’t present. Looking very attentively at the photo, he expressed how beautiful his mother was and realized that she didn’t deserve to suffer so much due to his father’s affairs.

I asked him about what he had in common with his father. He did not answer at all, and very suddenly put all the photos inside the folder. The mourning process of his father turned to be more difficult, and he didn’t want to talk much about him or identify himself with his father.

Two months later, he decided to buy a new analogic camera and took some pictures. The film was developed (like in the old days) and he was surprised with the result - the headless statues.

- “The statues were decapitated!” How astonished he was, when he said it..

- “In this way, we can give more value to feelings and not so much to the thoughts”, I said.

He quickly arranged the photos, as if he wanted to hide his failure, and asked to play Scrabble. He began to connect words easier and revealed pleasure with it.

Gradually, the patient become able to identify himself with his mother, and to integrate some parts of her in himself. In this way, the patient found space in his mind to manage the mourning process. Finally, the loss of his mother could be re-signified.

He brought his mother’s portrait, referring to how tender she had been with him. Then took out a sketch from his self-portrait (made by himself some time ago) and looked at both.

So, I mentioned the similarities in both profiles and asked him what he had in common with his mother. He laughed, thought a while, and answered:

The music, art, and painting, of course!”

Four months later, he showed a lot of anger, first at the maid (who stole things from his house) and then at his wife (she had fired the maid meanwhile). He confessed he just felt like throwing a book from D. Carlos I [1] at his wife’s head (since the maid left, he would have to find someone else to shave him). Then, he shared with me that his wife justified her decision, saying that I told her to fire the maid (which I had not done, of course). Then, he said how difficult it had been to live in a distrustful environment, and that he just realised he couldn´t trust anyone anymore.

What the patient is communicating to the analyst is very important and needs to be meta-analysed, into the implicit meaning, in a “here and now” experience. The countertransference communication made a big difference to the psychotherapeutic process development. The patient could feel understood, validated in his emotions, and leave the schizo-paranoid position and get into the depressive position.

Perhaps you also feel angry at me because you think I might have advised your wife to fire the maid, and now it seems to be difficult to keep our work within a trustful base”, I said.

- “Well... I do trust you! And I understand that she was stealing from us, but now I don´t have anyone to shave me”, he said.

- “A part of you is angry, because she deceived you, and another part is sad because it seems that there is no one to shave you”, I said.

- “Yes, she tricked me by being tender... I will frame my mother’s portrait, I miss her very much. If I would have known the cancer medication, I would have advised the doctors to treat her, as I already told you”, he said.

- “You are making good connections through the tenderness topic. The more you show your anger, the more you remember the things you have told me”, I said.

- “Well, here I can get angry”, he said.

The patient was not driving anymore, and he was aware of his difficulties, but it seemed he needed to begin mourning his autonomous skills.

He took the decision to drive his car, for the last time, and had an accident. Fortunately, he did not suffer from any injuries. He got really scared and took all the responsibility, realizing he did a stupid thing (as he named it). He admitted he could have hurt himself and others.

- “I wanted to say goodbye to my car, to remember my active life and when I worked,” he said.

I reminded him of the countless roads he had travelled, the number of hospitals from north to south he had known, and all the doctors he had met. He began listing the main cities he visited in the north of the country, and he said that he had decided to go south, to Alentejo [10] in order to meet some doctors and nurses. So, he was sure they (specially the nurses...) would remember him. He was remembering the affairs and the adventures he had lived and then he said:

- “This is something I got from my father. It is his legacy to me”. He laughed loudly.

Finally, the patient found space in his mind to manage the mourning process from the father’s loss. He was able to identify parts of his father and could integrate them in himself.

- “I have been so naive, if I catch her in front of me, I will punch her in the face”, he said.

- “You feel angry about the way she has deceived you”, I said.

- “I was stupid” (he showed internalizing ability).

- “It is good to receive tenderness”, I said.

- “Now, I have to shave myself, I did it today and I haven´t cut myself”, he said very proudly.

- “You can keep your abilities, and you don’t need others to do it for you”, I said.

After that session he began speaking about his own death, saying that if he would get a terminal disease, he would ask for euthanasia. Although he did not want to think much about it, he said he was not in a hurry.

- “The later it comes the better it is”, he said, laughing loudly.

To protect himself from the anguish the issue caused him, he said he was not afraid of dying. He used humour, laughing while saying:

- “I went to graze in Alentejo. It was raining a lot and I wasn’t able the control the car, so I met the field”, he said.

He mentioned he was planning to paint “Pessoa. [11] He loved the Poet and his personalities. I mentioned he wanted to find some parts of himself.

One of the activities he liked most, besides painting, was reading.

He said he bought a new book about the life of Camões. [12] He mentioned the poet lived in the year 1252 (XIIIthCentury), when he wanted to say 1524.

He referred that lately he has learned a lot (he learned a lot through emotional experiences too).

Working, still, in death anxiety, the patient reflected upon his marriage and confessed his wife did not deserve the several affairs he had.

He said he loved the book about Egyptian Culture and the one from D. Carlos I and then he mentioned while laughing:

- “The one I wanted to throw at my wife’s head”. Then he realized she was feeling very down. As he began crying, he seemed to be worried about it. He tried to wipe away his tears, shaking his head, trying to suppress his crying and stop the tears from falling.

- “I have to be strong”, he said.

- “And you are, as you feel the strength of being human, showing your tears”, I said trying to empathize and comfort him.

While he kept crying, he said that he must go away but in fact he did not want to leave the room and the feeling.

- “It is natural to be sad. Here we can give space to sadness”, I added.

Between tears he asked me to help him to communicate with his w,ife, he wanted to say how terrible he was feeling about “what happened” (this was the way he referred to the affairs), and how he appreciated her.

Although he was feeling so sad, he succeeded telling his wife all he wanted. She was very surprised by the information and in the end of the session he seemed much more relieved.

Seven months later, the patient decided to end the therapeutic process. During which he organized his thought, at least about several issues, made decisions, planned and achieved his main goals.

At the end of the therapy process it was possible to recognize the patient’s cognitive abilities (main executive functions) that were not shown in the evaluation phase. Unfortunately, after the therapy there was no opportunity to re-test in order to compare his neurocognitive progress, in an objective way. The patient’s cues suggested he wanted the analyst to be focused on the remembering (episodic memory) rather than the forgetting (cognitive dysfunction).

I learned from his wife that he died from a heart attack, one year later, very peacefully, (as she said) sitting in his sofa at home. Fortunately, he gave himself, before that, the chance to live emotional experiences and I am very happy that I had the chance to get to know him and learn with him.

[9] D. Carlos I was king of Portugal in the 19th century. He was murdered in 1908 and he is known for his high level of education and interests, e.g., leaving very interesting paintings.

[10] Alentejo is a portuguese region in southern Portugal where the landscape features undulating.

[11] Fernando Pessoa one of the greatest Portuguese poets, was born in 1888 and died in 1935. His modernist work gave portuguese literature European significance.

[12] Luís Vaz de Camões is a great national Portuguese poet who was born in 1524 and died in 1580, and wrote the epic poem “Os Lusiadas” (The Lusiads)

Despite brain injuries (frontotemporal dementia that affected the centre of decision) showed by the PECT results and cognitive dysfunction, presented in the neurocognitive evaluation results, the patient showed a strong will to talk about himself.

Through free association method he began to connect different meaningful words with his affective life experiences. At the very beginning, the patient used free association to express himself, which I misunderstood as a self-defence mechanism to handle with his tension. Each time he was not able to achieve desired results, expressed in his anguish and anxiety, he used free association to preserve his self-esteem, as suggested Hollós & Ferenczi (1925).

According to those authors brain injuries might lead to a psychological regression process to reveal episodic memories from his past. In terms of memory, the results showed a severe disturbance of the working memory, verbal and non-verbal as well.

Despite my misunderstanding of the patient’s intention when using free association, he did not give up and kept providing several cues, through drawing certain details, specifically, when he tried to give meaning to the circle in the Rey Complex figure, representing it as an human face, with a “shy smile.”

At this point I was able to interpret an attempt to establish an affective connection. Nevertheless, I wasn’t prepared to trust in the insight ability of the patient, as I was too involved in the forgetting dysfunction instead of the remembering function, due to the results.

In psychoanalysis the patient’s cues are inscripted in a compass, which leads the therapeutic process. According to Nancy MacWilliams (2004) the reverence and curiosity from the analyst are very important to believe in the patient’s cues, and in his insight ability to feel the emotional resonance in the “here and now” experience.

With the psychoanalytic approach the patient did improve his cognitive abilities, made decisions, organized his thought, and took actions to achieve his main goals. He could restore his trusting ability and feel the difference between what belongs to his internal world and what belongs to external reality. The meaningful materials (the patient’s personal objects) were the link to make free associations, as he needed to settle the affairs, and manage the anxiety of death. He concluded the mourning process of the meaningful losses and build up a more cohesive identity, connecting experiences from past with the present but above all, he found much more significance in the forgetting experience as he recognized the way he wanted to be remembered.1-18

Working as a psychotherapist at the clinic founded by Professor Dr. Carlos Amaral Dias, [13] one of the greatest Portuguese psychoanalysts, with a wide range of work, has allowed me to develop my therapeutic self, over the last 20 years. It has been mainly with my patients, from the youngest to the oldest, that I learn the most, listening, empathizing and questioning myself and my intervention methods. There aren’t two persons alike, and the answer must be adapted to each one.

[13] Carlos Amaral Dias is one of the greatest Portuguese Psychoanalist, who was born in 1946 and died in 2019, and authored several books. His main scientific interests were Psychoanalysis, Clinical Psychology, Mental Function of Psychopathology, Toxicaldependency and Psychose.

This Case Report received no external funding

Regarding the publication of this article, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- 1. Agrell B, Dehlin O. The clock drawing test. Age and Ageing. 1998;27:399-403.

- 2. Basilio M. Formação de palavras: conhecimento, representação e uso. Ed. Colibri. 2015:pp.103-115.

- 3. Britton R. Between mind and brain. Models of the mind ando models in the mind. 1st (edn). London: Karnac Books2, 2015.

- 4. Brundage SB. Comparison of proverb interpretations provided by right hemisphere-damaged adults and adults with probable dementia of the Alzheimer type. Clinical Aphasiology. 1996;24:215-231.

- 5. Caramelli P, Barbosa MT. Como diagnosticar as quatro causas mais frequentes de demência?. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2022;24:S7-S10.

- 6. Cooper S, Greene JDW. The clinical assessment of the patient with early dementia. J Neurol Neurosburg Psychiatry. 2005;76:S15-S24.

- 7. Gire J. How death imitates life: cultural influences on conceptions of death and dying. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2014;6(2):1-22.

- 8. Hollos S, Ferenczi. Psycho-analysis and the Psychic Disorder of General Paresis. New York and Washington: Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Co. 1925 (Monograph series, Nº 42).

- 9. Kamkhagi D, Costa ACO, Kusminsky S, et al. Benefits of psychodynamic group therapy on depression, burden and quality of life of family caregivers to Alzheimer’s disease patients. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2015;42(6):157-160.

- 10. Kesebir P. Existential functions of culture: the monumental immortality project. Oxford University Press. 2011:pp.96-110.

- 11. Klein M, Heimann P, Issacs S, et al. Developments in Psychoanalysis. The Hogarth Press Ltd., 1952:p.368.

- 12. Leicester J, Sidman M, Stoddard LT, et al. Some determinants of visual neglect. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1969;32:580-587.

- 13. Leyhe T, Saur R, Escweller GW, et al. Impairment in proverb interpretation as an executive function deficit in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2011;1(1):51-61.

- 14. MacWilliams N. Psicoterapia Psicanalítica. 1st (edn). Lisboa: Climepsi; 2006.

- 15. Mansur LL, Carthery MT, Caramelli P, et al. Linguagem e cognição na doença de Alzheimer. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica. 2005;18(3):300-307.

- 16. Mathews BD. Memory disfunction. Continuum. 2015;21(3):613-626.

- 17. Mondal S, Sharma VK, Das S, et al. Neuro-cognitive functions in patients of major depression. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;51(1):69-75.

- 18. Roca M, Manes F, Gleichgerrcht, et al. Intelligence and executive functions in frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51(4):725-730.