This study examines the variations in emotional intelligence and empathy between young and elderly persons, as well as how these traits affect daily life. The tests were applied to a group of 60 subjects, all representing the female gender. Participants belong to the age range between 16 and 80 years. Given the presented, the objectives of the paper are: To ascertain the differences in emotional intelligence and empathy between the two age groups. Only in the instance of emotional intelligence was the theory supported by statistical calculations. When it comes to empathy, there were no statistically significant differences, and the studies found explain why. Our premise is that these traits must be developed by any citizen, regardless of their status (educator, businessmen and leaders) in order to grow and develop the best quality of life.

Keywords: Adults, Differences, Empathy, Emotional intelligence

Empathy

Theodor Lipps, who introduced the term empathy into psychology at the beginning of the 20th century, is considered the father of the theory of empathy.1 In addition, the term empathy was introduced into clinical psychology in 1905, when Freud mentioned it in his work "Words of the Spirit" and in 1921 in "The Psychology of Crowds and Self-Analysis".2,3

Hogan, Premack and Woodruff and other early researchers and theorists claimed that empathy is primarily comprehending another person by understanding their thoughts, intentions, feelings, and beliefs.4,5 The founder of the Romanian school of empathy, Marcus, believes that empathy is a psychological phenomenon of experiencing the states, thoughts and behavior of others, achieved by transforming self-psychology into an objective model of human behavior and through which it is possible to understand how another person interprets the world.6 Present within “any relational behavior of the individual”, empathy can become a skill, a distinct, special competence, absolutely necessary for the exercise of professional roles.3

Because their importance and ubiquity, extensive research focus on the role and impact of empathy subsequent behavior and underlying mechanisms.7,8

These studies primarily emphasize the role of empathy in our responses to the physical pain of others, the situation of translating to the other side gives us the opportunity to establish a filter of understanding, but above all to understand the interlocutor and expect certain actions. This helps develop a true “joint strategy”.3

Leonardo Badea and Nicolae Alexandru Pana9 explain the importance of this phenomenon: Empathic concern is the tendency to feel empathy and to care about feeling others.10

Emotional intelligence

The concept of emotional intelligence (EI) was first proposed by Salovey and Mayer.11 It describes the capacity to identify, feel, and manage one's own emotions as well as those of others.The term emotional intelligence was first used academically by Wayne Leon Payne in his doctoral dissertation in 1985.12

Daniel Goleman13 described emotional intelligence as occasionally stronger than IQ in prognosticating success in life. He suggests that a high position of emotional intelligence can ameliorate interpersonal and professional connections, help develop problem- working chops, increase effectiveness, and lead to new strategies. Likewise, Por and his associates14 tell us that people with high emotional intelligence tend to have advanced social competencies and richer forms of social.

Understanding the concepts and meanings of emotions, their interactions, the causes behind them, and how to solve problems based on them is what is meant by having emotional intelligence.15 Instead, the characteristics of emotional intelligence are seen as a constant group of characteristics connected to how a person gestates, expresses, and comprehends feelings.16 Emotional intelligence, according to Mayer,17 also refers to the capacity to integrate intelligence, empathy, and emotion to improve reasoning and comprehension of interpersonal dynamics.

It was observed in the literature that gaps in emotional intelligence capacities affect individualities in both prefessional life and other spheres. further studies demonstrated that high emotional intelligence is associated with lesser well- being in all areas.18-22

Recalling Goleman's13 theory that emotional intelligence is a construct of socio-emotional skills that supports the logical dimension of personality and enhances adaptability in every environment, we can draw this conclusion.

The explanatory model of personality proposed by costa and McCrae (Big five)

Costa and McCrae23,24 present their concept for the five superfactors of personality evaluation for the first time in July 1994 in Madrid (the Big five model). According to Costa and McCrae, the basic characteristics of neuroticism, extraversion, affability, and meticulousness show as abecedarian psychological dispositions. We shall succinctly outline the factors that frame the structures of our study from these five factors.

Agreeableness

The angles of this dimension, according to Plato, are modesty, perceptivity, trust, altruism, compassion, justice, and compliance. According to Constantin and his coauthors, people who have a high position of compassion and empathy are novelettish and feel affected by the problems of others, suffer with others, and show compassion and understanding in fact to those who have dissatisfied them.15

Conscientiousness

The aspects of this dimension, according to Plato, are competitiveness, order, sense of responsibility, success, tone-discipline, and contemplation. According to Constantin and his colleagues,25 people with high levels of conscientiousness, or emotional intelligence (EI), are ambitious, systematised, and scrupulous, and they have confidence in their abilities to deal with unforeseen problems.

Objectives and Hyphotheses

This research was conducted to discover the level of emotional intelligence and empathy among adults and the impact they have on everyday life. The aim is to find out the age differences in the level of the two concepts mentioned above, among young and older adults.

Hypothesis 1: There are presumed to be significant differences between young and older adults in terms of empathy.

Hypothesis 2: There are presumed to be significant differences between young and older adults in terms of emotional intelligence.

Lot of participants

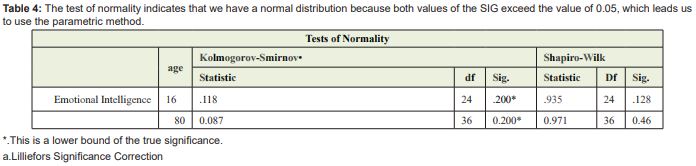

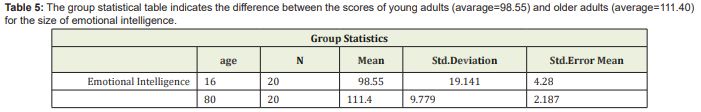

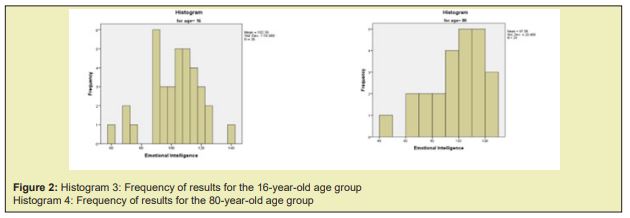

The tests were applied to a group of 60 subjects aged between 16 and 80, all representing the female gender. Also, a number of 24 participants come from rural areas and the remaining 36 from urban areas.

Description of the used methods

The tools used consisted of questionnaires built by us, questionnaires that were applied successively, the first form comprising 150 items. Following the elimination of the questions that did not comply with the normality, we applied the final form of the questionnaire, which includes 60 items (30 items on each scale).

The Big five personality questionnaire was used among the established tools by me. This questionnaire evaluates adult personality through 151 items based on a psycho-lexical approach that is consistent with the Big five system. This questionnaire evaluates 5 areas of personality: Extraversion, maturity, agreeableness, conscientiousness and self-actualization. From these 5 areas we have chosen items that belong to empathy as a facet of agreeableness.

The International Personality Item Pool by Dragos Iliescu and his collaborators26 was used for emotional intelligence. The International Personality Item Pool article bank contains 2504 items used for personality assessment. They describe a number of 371 personality scales, organized into 19 categories according to the original The International Personality Item Pool model.27 Also, The International Personality Item Pool items have response variants evaluated on a Likert scale with 5 levels.

Data Analysis and Processing

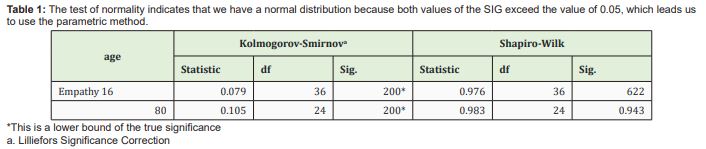

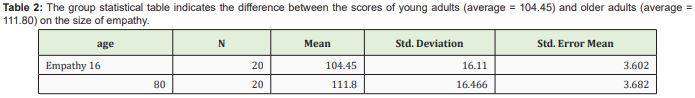

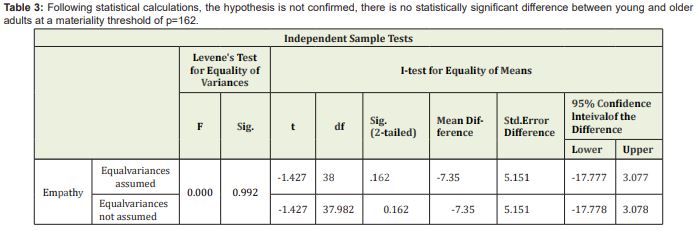

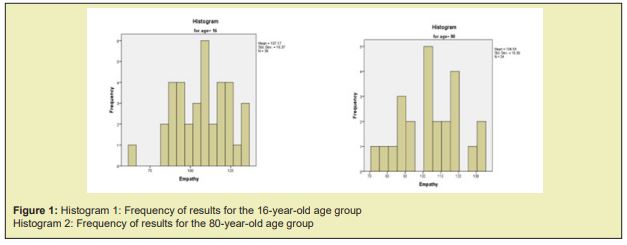

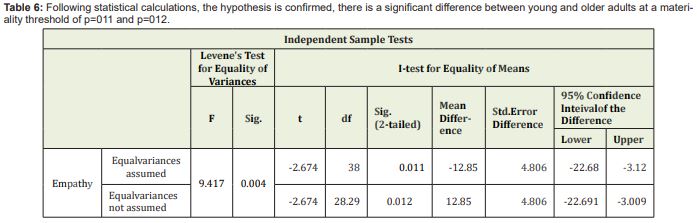

Hypothesis 1: It is assumed that there is a significant differences between young and older adults in terms of empathy.

Given that the outcome does not support our proposed hypothesis, we have looked for studies using the literature as a source to support our finding. Since there may be age differences in empathy, evidence suggests that these differences may not always have a statistically significant coefficient.

Most studies focus on humane concern traits using Interpersonal Reactivity Index and a sizable number show no significant age- related.28,29 As a result of our research, Bailey and his colleagues30 carried out two tests evaluating empathy on a group of actors ranging in age from 16 to 87 without finding any appreciable variations in the empathy subscale due to age. In the alternate study, the authors used Interpersonal Reactivity Index to measure age- related differences between youthful and aged grown-ups in humane concern and particular suffering. Additionally, there were no established age-related changes in emotional empathy qualities.

According to research by Chen and his colleagues,31 older adults are just as likely as younger adults to understand emotional stimulants.32-34 One theory is that empathy is essential for adaptation and social group integration throughout life and fulfils the adaptive social function.31

Hypothesis 2: There are presumed to be significant differences between young and older adults in terms of emotional intelligence.

According to Gardner and Qualter,35 the capability of emotional intelligence should meet the requirement of growth development with age and experience, from early majority to nonage, if it is included in an intelligence frame.36 The acquisition of knowledge may also lead to absolute conditions of Emotional Intelligence increasing beyond early majority, similar to other cognitive capacities as shown by Kafetsios.37,38

Harmonious with the idea that emotional geste improves through lifelong literacy and practice, tone- reporting studies contrasts with the results of our study indicating that aged grown-ups are more confident that they can control their feelings toward youngish grown-ups.39-41

According to Gross,39 emotions can be controlled in a variety of ways and at various stages of the emotion-generating process. Making the distinction between responding and managing feelings that are antecedent-focused is helpful. Charles and Carstensen42 conclude that older adults likely have an edge in daily life due to antecedent regulation, environment selection, and the employment of cognitive methods that target emotional gests before they happen. Additionally, older adults exhibit and perceive less wrath in interpersonal conflict situations;43,44 they also choose more effective problem-solving techniques,45 combining necessary and emotion-regulating techniques.46

As for the hypothesis that targets age differences in empathy, the results indicated that there may be differences, but not statistically significant. In this case, the research hypothesis has not been confirmed, which led us to seek in the literature studies to support our result. Following the documentation, the conclusion is that empathy is an indispensable resource for all adaptive social functions, regardless of the period of the individual’s life, contributing both to adaptation and integration into social groups. Knowing the thoughts and transposing into the situations of others helps us to pass through the mind filter the actions that those around us take, which facilitates the building and maintaining of interpersonal relationships as efficiently as possible.

On the other hand, the hypothesis that supports an age difference in emotional intelligence achieved a result that shows a statistically significant difference between young and older adults, and therefore the hypothesis was confirmed. Thus, the results of our research are in line with most of the studies conducted over the years that prove that older adults have higher emotional intelligence levels than younger ones due to the fact that the long-life experience and the various events experienced by older adults determine them they have a greater ability to manage emotions and understand them. In addition, with age, the individual learns to apply various cognitive methods or strategies as effectively as possible for conflict resolution.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Dimitriu GO. Empatia în psihoterapie. București: Ed. Victor. 2004.

- 2. Constantinescu M. Competenţa socială şi competenţa profesională. Bucureşti: Ed. Economică. 2004.

- 3. Vicol MI. Comunicarea, empatia şi asertivitatea, de la abilitate la competenţa psihosocială In: Studia Universitatis Moldaviae (Seria Ştiinţe ale Educaţiei). 2011;9(49):58–63.

- 4. Hogan R. Development of an empathy scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33(3):07–316.

- 5. Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1978;1(4):515–526.

- 6. Potâng A, Bolocan L. Empatie şi creativitate. In: Studia Universitatis Moldaviae (Seria Ştiinţe ale Educaţiei) nr. 2009;9(29):180–184.

- 7. Jackson PL Meltzoff AN, Decety J. How do we perceive the pain of others? A window into the neural processes involved in empathy. Neuroimage. 2005;24(3):771–779.

- 8. Singer T, Seymour B, O'doherty J, et al. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303(5661):1157–1162.

- 9. Badea L, Feather AN. Rolul empatiei în dezvoltarea inteligenţei emoţionale a liderului. Economie teoretică şi aplicată. 2010;2(543):41–45.

- 10. Gorniewicz JS. Do Adult Romantic Attachment Empathy and Social Skills Influence Mate Poaching Infidelity?. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2011; pp.1311.

- 11. Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, cognition and personality. 1990;9(3):185–211.

- 12. Gardner H. Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice. New York: Basic Book. 1993.

- 13. Goleman D. Inteligența emoțională: de ce poate conta mai mult decât IQ. Cărți Bantam. 1995.

- 14. Por J, Barriball L, Fitzpatrick J, et al. Emotional intelligence: its relationship to stress, coping, well-being and professional performance in nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(8):855–860.

- 15. Ciarrochi JV, Chan AY, Caputi P. A critical evaluation of the emotional intelligence construct. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;28:539–561.

- 16. Petrides KV, Furnham A. On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Personality and individual differences. 2000;29(2):313–320.

- 17. Mayer JD, Roberts RD, Barsade SG. Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual review of Psychology. 2008;59(1):507–536,

- 18. Brackett MA, Rivers SE, Shiffman S, et al. Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: a comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(4):780–795.

- 19. Ciarrochi J, Chan AY, Bajgar J. Measuring emotional intelligence in adolescents. Personality and individual differences. 2001;31(7):1105–1119.

- 20. Trinidad DR, Johnson CA. The association between emotional intelligence and early adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Personality and individual differences. 2002;32(1):95–105.

- 21. Austin EJ, Saklofske DH, Egan V. Personality, well-being and health correlates of trait emotional intelligence. Personality ssand Individual Differences. 2005;38(3):547–558.

- 22. Palmer B, Donaldson C, Stough C. Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;33(7):1091–1100.

- 23. Minulescu M. Chestionarele de personalitate în evaluarea psihologică. București: Garell Publishing House. 1996.

- 24. Minulescu M. BIG FIVE. ABCD-M. Cluj: Ed. Sinapsis. 2008.

- 25. Constantin T, Macarie A, Gheorghiu A, et al. Chestionarul Big Five plus–Rezultate preliminare. M. Milcu, Cercetarea Psihologică Modernă: Direcţii şi perspective. 2008; pp.46–58,

- 26. liescu D, Popa M, Dimache R. Adaptarea românească a Setului International de Itemi de Personalitate: IPIP-Ro. Psihologia Resurselor Umane. 2019;13(1):83–92.

- 27. Goldberg LR, Johnson JA, Eber HW, et al. The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:84–96.

- 28. Bailey PE, Brady B, Ebner NC, et al. Effects of Age on Emotion Regulation, Emotional Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(4):802–810.

- 29. Gross JJ, Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, et al. Emotion and aging: experience, expression, and control. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(4):590–599.

- 30. Bailey PE, Henry JD, Von Hippel W. Empathy and social functioning in late adulthood. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(4):499–503.

- 31. Chen YC, Chen CC, Decety J, Cheng Y. Aging is associated with changes in the neural circuits underlying empathy. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(4):827–836.

- 32. Keightley ML, Winocur G, Burianova H, et al. Age effects on social cognition: faces tell a different story. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(3):558–572.

- 33. Mather M, Knight MR. Angry faces get noticed quickly: Threat detection is not impaired among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(1):54–57.

- 34. Levine LJ, Bluck S. Experienced and remembered emotional intensity in older adults. Psychology and aging. 1997;12(3):514.

- 35. Gardner KJ, Qualter P. Factor structure, measurement invariance and structural invariance of the MSCEIT V2. 0. Personality and Individual Differences. 51(4):492–496.

- 36. Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P. Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence. 1999; 27(4):267–298.

- 37. Kafetsios K. Attachment and emotional intelligence abilities across the life course. Personality and individual Differences. 2011;37(1):129–145.

- 38. Kaufman AS, Johnson CK, Liu X. A CHC theory-based analysis of age differences on cognitive abilities and academic skills at ages 22 to 90 years. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2008;26(4):350–381.

- 39. Gross JJ. Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1998;74(1):224.

- 40. Kessler EM, Staudinger UM. Affective experience in adulthood and old age: The role of affective arousal and perceived affect regulation. Psychology and aging. 2009;24(2):349.

- 41. Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Rajagopal D, et al. Dimensions of affective experience in three age groups. Psychology and aging. 1992;7(2):171.

- 42. Charles ST, Carstensen LL, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and aging, Handbook of emotion regulation. New YorkGuilford. 2007;p.307–327.

- 43. Bucks RS, Garner M, Tarrant L, et al. Interpretation of emotionally ambiguous faces in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63(6):P337–P343.

- 44. Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Unpleasant situations elicit different emotional responses in younger and older adults. Psychol Aging. 2008;23(3):495–504.

- 45. Birditt KS, Fingerman KL, Almeida DM. Age differences in exposure and reactions to interpersonal tensions: a daily diary study. Psychol Aging. 2005;20(2):330–340.

- 46. Blanchard Fields F. Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult developmental perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16(1):26–31.