This paper was written in consultation with three colleagues for presentation at the IFPS VIII FORUM – Rio de Janeiro Brazil. The current version has been reviewed and updated. The intention was to verify if the phenomena of Transference occurring outside the psychoanalytical setting would be affected by the culture in which it occurred. The results showed that cross-cultural differences impact the manifestation in how the transference occurs.

Transference is a phenomenon that, since its identification and description by Freud,1-6 has been the focus of study7-11 by those interested in the psychological principles of human interaction. Clara Thompson12 stated that “transference was not created by psychoanalysis. As long as human beings have had relationships with each other, there have probably been irrational elements in those relationships” (p. 273). According to her, these irrational elements have been quite evident in those relationships in which one person was in a position of authority. She pointed out that “when Freud first described the phenomena which he grouped under the name transference, he was merely clarifying something which has been used unwittingly by physicians in their treatment of the sick throughout the ages” (p. 273). She goes on stating that there is usually an element of dependency involved in these relationships. The other person is quite often placed in a position of authority either by the patient or circumstances. Therefore, not only physicians, but teachers, employers, supervisors, sometimes even a spouse or friend if the patient is dependent on them emotionally, financially, or any other manner, may be the recipients of transference reactions.

Saravay,13 looking at psychoanalytical concepts when applied to the treatment of the medically ill, pointed out that these patients are very often in a regressed state and “in a state of transference readiness.” Such concepts have been the focus of observation by other authors in the field Baudry and Wiener,14 Grossman,15,16 and Kernberg.17 According to Baudry and Wiener,14 in these patients, the most common defense mechanisms used are denial, regression to a more childlike attitude, with “passive surrender and over idealization of the hospital and the surgeon” (p. 124). This idealization in the transference is a concept that has been largely described by Kohut18,19 in his treatment of narcissistic patients. Without fully endorsing his explanation of the phenomena, but rather as an empirical observation, idealization is here understood as a feature of the transference. In it, the love object is invested with powers, and usually, such a love object is overly idealized. Kohut talks about this aspect of the positive transference, stating that it is “closely akin to that encountered in the state of being in love” (p. 55).

A year after this paper was presented at the FORUM (1989), William M Zinn,20 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, addressed the “Transference Phenomena in Medical Practice: Being whom the patient needs” with illustrations, namely case studies from his own medical practice. With sound knowledge of psychological treatment when dealing with transference, he states that “Less interpretive ways of dealing with transference phenomenon can also be psychological therapeutic. Such therapeutic methods may result from physicians’ responses to the types of relationship sought by their patients” (p. 294). For him, paying attention to transference issues will help physicians to transcend the barriers to effective physician-patient relationships, thus allowing physicians to be whom the patient needs.

Another important study, very pertinent to this paper, was also published nine years after our presentation at the FORUM. Using a social cognitive model, Susan M Andersen and Michele S Berk21 in the article “Transference in Everyday Experience: Implications of Experimental Research for Relevant Clinical Phenomena” demonstrated that mental representations of significant others are stored in memory and applied to new social encounters with consequence for affect, motivation, cognition, expectations, and self-evaluation. Such findings are an empirical demonstration of transference in everyday social relations both inside and outside psychotherapy.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between patients and their doctors from different cultures and outside the psychoanalytical setting. The medical specialty chosen was obstetrics/gynecology. The relationship between the patient and the obstetrician-gynecologist is a very personal one, possibly more intimate than any other medical specialty, with the exception of psychiatry. Many times, however, the woman’s expectation, consciously or unconsciously, is to have her gynecologist as her confidant, her helper and savior, as Freud4 wrote:

“…now that the force of public opinion drives sick women to the gynecologist, he has become their helper and saviour.”

It is easy to understand the development of such expectations if one considers that the woman’s body is examined by the gynecologist in the most vulnerable of positions and that he deals with some of the most sensitive issues in her existence: sexuality and reproduction. Any Home Medical Guide will tell the woman the importance of choosing her OB/GYN not only in terms of medical credentials but also regarding his or her capacity to have a warm trusting rapport with the patient.22

Another aspect of the relationship between women and their obstetrician/gynecologist, mainly patients that undergo surgeries, is flirtation. Such phenomena have been described by Nancy C A Roeske23 when discussing the relationship between surgeon and patient in gynecological surgeries. She points out that “the surgeon may be the object of flirtatious seductive behavior or excessive dependency. The latter behavior may represent regression, assumption of the stereotypic feminine passive role, and a reaction formation against anger toward the man in power who has taken away a valued part of a woman’s identity. Through the former sexualized behavior, the woman seeks reassurance that she is still physically attractive” (p. 226).

The nature of transference seems to be quite different if one is dealing with transference in a psychoanalytic setting or in a different context from the one described above. Ornstein (1985), after stating that transference arises spontaneously in any extra therapeutic, every day, close relationship, pointed out that the setting contributes to what will emerge in the transference, but its special quality will arise only in the psychoanalytic setting.

Literature testing the theory of transference has not attracted much attention of researchers. Luborsky24 observed that in rereading Freud’s 1912 paper on transference, it became evident that Freud’s diverse and concrete observations about transference go beyond the usual definitions. They tried to test the numerous assertions about transference as generalizability, relation to childhood patterns, consistency of the pattern, the pattern being specific to each person, the pattern applying to love relationships, etc. Their findings give evidence for a general transference phenomenon.

After this paper was written, as mentioned before, the study by Susan M Andersen and Michele S. Berk21 expanded and enriched Luborsky findings.

The connection between psychology and gynecological problems has received more attention, but no studies have addressed, in terms of research and theory, the relationship between a woman and her OB/GYN.23,24-27

The present study was done in order to assess transference occurring outside the psychoanalytical setting, namely in the OB/GYN one, and if the phenomena would be similar in its basic elements or manifestations when two different countries, specifically Brazil and the United States, were to be compared.

Subjects

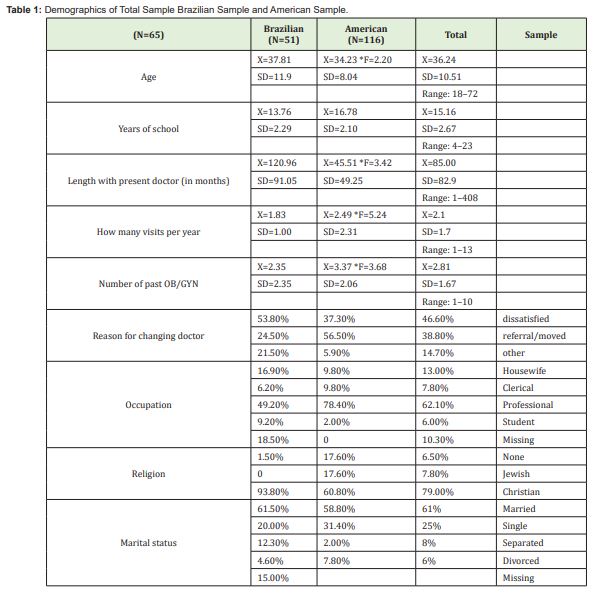

The sample was composed of 116 women. Of these 116 women, 65 were from Brazil and 51 from the U.S., ranging in age from eighteen through seventy-two (M=36.24, SD=10.51). The years of school ranged from four to twenty-three (M=15.16, SD=2.67). Their length of time with present OB/GYN in months ranged from 1 to 408 (M=85, SD=82.9). In terms of occupation, 13.0% of these women were housewives; 7.8% clerical; 62.1% professional; 6% students; and 10.3% did not answer the item on occupation. Their marital status was: 61% married, 25% single, 8% separated, and 6% divorced See Table 1.

Instrument

A questionnaire divided into five parts was devised. Section I contains a request for a brief description of the current OB/GYN. Section II and III were made up of sixty four items measuring perceptions, feelings, and fantasies about the OB/GYN. Half of these items, thirty two, were adapted from the Yale Psychotherapy Project Questionnaire while the other half were taken from Barret-Lennard Relationship Inventory. Section IV has items inquiring about the dreams concerning the OB/GYN. Finally, Section V contains twenty-one items taken from the 16 PF and measures the level of neuroticism of each subject.

Procedure

The complete questionnaire containing all the questions and background information was first written in English. It was then sent to Brazil, where it was translated into Portuguese. The Portuguese version was then translated back into English, and this second English version was compared and corrected. A final version in Portuguese was then made.

The English and Portuguese versions were then administered to subjects in each country. The questionnaires were given to each subject in a stamped envelope addressed to one experimenter in each country. They were told that the information would be kept anonymous. In both countries, the patients were sampled from male OB/GYN. For the U.S., they were from the practice of two OB/GYN, whereas in Brazil, they were from several.

Analysis of variance were used to compare the two cultures for

- The demographic information

- Individual items on the questionnaires

- The stable-unstable factor from Cattell 16 PF questionnaire

Correlations were calculated between individual items that indicate positive regard for the OB/GYN.

The two groups differ demographically in age (Brazilians slightly older; F=2.20); in length of time with their present doctor (Brazilians have been with their doctors longer: F=3.42); in number of past OB/GYN (Americans tend to change OB/GYN more often: F=3.68); and in the number of visits per year (Americans have more visits to the OB/GYN [F=5.24] than Brazilians).

Only four of the thirty-two items of Section II were rated differently for the two groups.

Inter-item correlations indicated an overall internal consistency. Items that reflected similar attitudes about the OB/GYN were rated alike.

There is little evidence for erotic transference reactions in the sample as a whole. The women do not agree with questions that romanticize the relationship (such as #15: “I wish more of my relationships were like the one with my doctor,” and #11: “No one can replace my doctor in my life”). However, they are in agreement with items that express idealization of the OB/GYN, such as his relationship with his children (#22: “My doctor’s children are lucky because they always have someone nearby when they are sick”), with his wife (#26: “My doctor’s mate is envied by other men/women”), as well as his nurse (#28: “My doctor’s nurse is closer to him or her than his or her spouse”). In all these relationships, the OB/GYN is perceived in a very positive, idealized manner.

The women from both countries felt understood and respected by their doctors. These items (understanding #7 and respect #1) correlated with a number of other items in the expected direction. In general, they report a very positive attitude with their doctor, even at a level that is characteristic of patients in psychotherapy.

Section I (description of the OB/GYN) and Section IV (dreams about OB/GYN) were analyzed from an interpretive, psychoanalytical point of view, rather than analyzed statistically. Although transference is an unconscious phenomenon, it appears that people feel less defensive when faced with material that is less structured and more ambiguous (“Describe your OB/GYN.” No explanation was given about what kind of description had been asked for) than when rating an item like: “I have imagined myself being caressed by my doctor” (Section III, #32). The same holds true when asked to describe any dream that the patient may have had about the OB/GYN.

Cross-cultural analysis and interpretation of these two sections revealed interesting differences. On the Brazilian sample, 39% of the patients described their doctors with an emphasis on physical looks. “He has a thick moustache which is his main characteristic,” or “He has strong, warm, firm hands,” etc. Even when one takes into consideration the stereotype that Brazilians are externally oriented and quite aware of their own as well as others’ looks, the data seems to indicate a clear focus on the OB/GYN primarily as a man.

He is a man who happens to also be a doctor. Most of these physical descriptions have an erotic connotation to them. Other relevant descriptions were: 28% of the sample described their doctors in an idealized professional way (“He is the best doctor in the whole world, quite well known in his field”), 23% saw him as a father figure. In contrast, in the American sample, 63% of the patients described their OB/GYN as a fatherly figure with emphasis on the psychological, emotional attributes. The concern with physical traits or the gynecologist as a man appeared in only 23% of the descriptions.

American women in this study appear much more involved emotionally with their doctors than their Brazilian counterpart. Their feelings toward their doctors are very positive; the OB/GYN is perceived in an idealized, fatherly manner. These findings agree with the demographics of the sample. In it is shown that American women seem to be more informed than Brazilian women about the gynecological care they should be receiving. This factor appears to be linked to the frequency of the visits to the OB/GYN by the American women as well as to their tendency to change doctors.

In the section on dreams, the American patients reported three times as many dreams as the Brazilians. In both samples, (Brazilian 100%) the dreams seemed to occur when the patient was pregnant and the OB/GYN appeared as the soothing, comforting, reassuring father figure. Although pregnancy is not an illness, the patient feels vulnerable and regresses to a childlike attitude, resembling the medically ill patient described by Baudry and Wiener. Like those patients, the pregnant women displayed a tendency toward a passive surrender and idealization of the OB/GYN. Some of the dreams include scenes that are reminiscent of early childhood, where the doctor is clearly replaying the father. In one dream, the patient is waking up from the anesthesia and the OB/GYN is holding her hand and kissing her on the forehead. In another dream, the patient is eating a meal while the gynecologist is standing up and singing French songs to her.

Waking up from anesthesia (which can be seen as waking up from deep repressed Oedipal love), the OB/GYN, like a father, omnipotent being, or even lover (sleeping beauty), kisses the patient on the forehead. The dream, which contains clear Oedipal implications, indicates that the relationship with the doctor is producing the awakening of such repressed material. The pregnancy and the frequent interaction with the OB/GYN create the scenario in which the patient’s “buried and forgotten love-emotions” can be unconsciously relived.

In the second dream, it appears that orality-dependency is being re-enacted and the patient is regressing to the Oedipal phase. The OB/GYN that sings French songs is probably the father who told stories, sang songs at bedtime, and for whose comfort and nurturing the patient is longing.

It can also indicate conflicts over the new role that she is getting ready for with the help of her doctor. The role of being a parent, the one who is going to feed, to provide nourishment.

Most of the dreams give evidence to the fact that in this study, the relationships of pregnant women with their OB/GYN is colored by the awakening of their struggles with Oedipal wishes.

In this study, the basic hypothesis paraphrasing Racker,30 that the childhood-acquired way of “living one’s love” from which arises the pattern of relating) will be repeated by women in their interactions with their OB/GYN differently according to the culture in which it occurs. In spite of the many limitations of this research, the findings agree with the hypothesis. In the OB/GYN setting, transference in its manifestations occur according to the emotional characteristics of a given country.

The findings showed how a culture shapes different expressions of the same phenomenon. In other words, cross-cultural ways of relating are responsible for the difference in the expression of the transference. Brazilian women in this sample emerged as having a rather superficial, defended relationship with their OB/GYN. They displayed intense need to trust their doctor, to see him as being competent and knowledgeable but not someone with whom to discuss the problems concerning their sexuality. They seem to try to relate to him just at the biological level, separating the biological body from the body that is also desire, wishes, and emotions. This seems to explain the emphasis on the physical characteristics when asked to describe their doctors as well as the low incidence of dreams. They stay long periods of time with the OB/GYN, have positive feeling towards them, but do not develop an open interaction. They also seem less informed and less curious about their gynecological problems than their American counterparts. In this particular way of interacting, Brazilian patients in the sample seem to have a collusion with their OB/GYN: the patients do not want to know, and their doctors do not want to ask. The kind of interaction between the patient and the OB/GYN that could be personal and more involved is left repressed and perhaps displaced into the stories (love stories) that are abundant in the type of magazines that are on display in most waiting rooms of Brazilian OB/GYN.

On the other hand, the women in the American sample appeared as having an emotional, involved relationship with the OB/GYN. They seem to be quite informed and demanding (if the OB/GYN does not meet their expectations, they will change to another one) and have more visits per year than the Brazilians. Their feelings toward their doctors are very positive, and they own their positive relationship with them. They seem to experience less threat from their feelings; therefore, there is no need to disown those feelings as the Brazilians seem to do. The result of this positive interaction is a very idealized relationship in which the OB/GYN is perceived most of the time as a father figure.

In conclusion, in this study, women from both countries have very positive relationships with their doctors. There is evidence that the way transference in both samples was manifested was quite marked by cross-cultural differences. Americans seem to see their doctors as trusting, worthy, caring, kind, and omnipotent father figures who will not make mistakes. In this kind of interaction, they seem to have characteristics of the Oedipal level of the psychosexual development. Brazilians appear to be in another level of their development. They seem to be beyond the level of adolescence, or maybe in adolescence, where erotic feelings are quite often feared. So, they protect themselves from perceived dangers (erotic) in relating to a doctor that they want to keep distant because they are equal possible sexual partners.

None.

None.

None declared.

- 1. Freud S. The psychotherapy of hysteria. S.E. 1895;p.253–305.

- 2. Freud S. The interpretation of dreams. S.E. 1900;p.550–572.

- 3. Freud S. Fragment of an analysis of a case of hysteria. S.E. 1905;p.7–122.

- 4. Freud S. The future prospects of psychoanalytic theory. S.E. 1910;11:139–151.

- 5. Freud S. The dynamics of transference. S.E. 1912;12:99–108.

- 6. Freud S. An autobiographical study. S.E. 1925;20:7–74.

- 7. Sandler J, Dare C, Holder A, et al. The patient and the analyst: The basis of the psychoanalytic process. London: Maresfield Reprints.1973.

- 8. Gill MM. Analysis of transference. Theory and technique. Psychological. 1982;53:1–193.

- 9. Gill MM. The interactional aspect of transference range of application. In: Schwaber EA. editor. The transference in psychotherapy: Clinical management. New York: International University Press, Inc. 1985.

- 10. Schimek JG. The construction of the transference: The relativity of the “here and now” and the “there and then.” Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought. 1983;6(3):435–456.

- 11. Singer JL. Transference and the human condition: A cognitive-affective perspective. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 1985;2(3):189–219.

- 12. Thompson C. Transference as a therapeutic instrument. Psychiatry: Journal of the Biology and Pathology of Interpersonal Relations. 13. 1945;8(3):273–278.

- 13. Saravay SM. Psychoanalytic concepts in the general hospital and the transference cure. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. 1984;10:549–566.

- 14. Baudry FD, Wiener A. The surgical patient. In: Strain JJ, Grossman S, editors. Psychological care of the medically ill: A primer in liaison psychiatry. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1975.

- 15. Grossman S. The use of psychoanalytic theory and technique on the medical ward. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. 1984;10:533–548.

- 16. Strain JJ, Grossman S. Psychological care of the medically ill: A primer in liaison psychiatry. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. 1975.

- 17. Kernberg O. Object-relations theory and clinical psychoanalysis. New York: Jason Aronson, Inc. 1976.

- 18. Kohut H. The analysis of the self. The University of Chicago Press. 1971.

- 19. Kohut H. The restoration of the self. The University of Chicago Press. 1977.

- 20. Zinn WM. Transference phenomena in medical practice: Being whom the patient needs. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113(4):293–298.

- 21. Andersen SM, Berk MS. Transference in everyday experience: Implications of experimental research for relevant clinical phenomena. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2(1):81–120.

- 22. The Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Complete Home Medical Guide. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. 1985.

- 23. Roeske NCA. Hysterectomy and other gynecological surgeries: A psychological view. In: Notman MT, Nadelson CC, editors. The woman patient, 1. New York: Plenum Press. 1978.

- 24. Luborsky L, Mellon J, van Ravenswaay P, et al. A verification of Freud’s grandest clinical hypothesis: The transference. Clinical Psychology Review. 1985;5(3):231–246.

- 25. Castelnuovo Tedesco P, Krout BM. Psychosomatic aspects of chronic pelvic pain. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1970;1(2):109–126.

- 26. Lipsitt DR. The painful woman: Complaints, symptoms, and illness. In: Notman MT, Nadelson CC, editors. The woman patient, 3. New York: Plenum Press; 1982.

- 27. Tishler SL. Breast disorders. In: Notman MT, Nadelson CC, editors. The woman patient, 1. New York: Plenum Press. 1978.

- 28. Broome A, Wallace L. Psychology and gynaecological problems. New York: Tavistock/Methuem, Inc. 1984.

- 29. Cutler WB. Hysterectomy: Before and after. New York: Harper and Row, Publishers; 1988.

- 30. Racker H. Transference and countertransference. London: Maresfield Library; 1968.