The present study identified the conceptualization and construction of an emotional fitness profile in a modern Asian society, Singapore. This study consists of 311 participants who completed the self-report questionnaire. The emotional fitness profile comprised of five dimensions: Identifying emotions of self; Identifying emotions of Others; Ability to cope with emotions (self and social support); Emotional Regulation; and Neuroticism.

Keywords: Emotions, Emotional fitness, Emotional intelligence, Resilience

Definition of emotional fitness

Emotional Fitness refers to one’s ability to understand that emotions provide information to the situations around us. It consists of a) one’s ability to identify, express, and regulate their emotions; b) Seeking social support. Individuals who are high in emotional fitness are also better able to perceive challenges as manageable rather than feeling overwhelmed. They also have greater mental and emotional resources to help them bounce back from setbacks and continue stronger than before.

These components are chosen as research suggests that individuals who are able to recognize, understand, regulate, and effectively manage their emotions are likely to experience a higher level of psychological well-being and maintain a positive mental state.1,2 Salovey & Mayer2 also showed that the ability to monitor one's own emotions, as well as that of others, and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions contributed significantly to the explanation of one’s positive mental health. In addition, this ability can also help individuals to recognize how their decisions can be influenced by their emotional states.3

Furthermore, people who are particularly adept at self-generating positive emotions are more likely to be resilient by bouncing back from setbacks.4 In addition, having better social support networks in general, has been shown to have a strong inverse association with mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and hostility and a strong positive association with physical health as well as longevity.5-7 The presence of social support is also vital in building one’s resilience in the workplace. Past research examined students wellbeing and had also shown that social support can be particularly beneficial for them to develop a ‘community of learning’, a healthy coping strategy when coping with academic stress.8

Cultural differences in expressing emotions

It is important to note that there exist differences in how emotions are expressed in different cultures. Cultures that are more individualistic value high arousal emotions, whereas more collectivistic cultures value low arousal emotions.9 Westerners experience more high arousal emotions, compared to collectivist cultures.9 In Western cultures, people express themselves and try to influence others, which makes high arousal emotions fitting of their culture.10 In contrast, in collectivist cultures, adjusting and fitting into a social environment is ideal and hence, lower emotions such as calmness and controlled emotions are more appropriate many context of the culture.10 Similarly, according to Matsumoto & Ekman, 1989,11 individuals from Asian countries attributed their emotions less intensely compared to individuals from the United States. The researchers for this study also suggested that Asian individuals show such patterns of emotional expression due to culturally learnt display rules which prohibits public expression of negative emotions.

What's lacking in asia and why we are developing EF Programmes

In Singapore, there have been calls by mental health professionals and advocates to increase the emotional literacy of youths, in order to bring about greater mental wellness in the society.12 It is crucial to build emotional fitness as it teaches individuals how to manage their emotions, increase cognitive flexibility, and build resilience. Hence, we aim to develop an emotional fitness profile that can be used in Asia to examine an individual’s level of emotional fitness, which in turn affects the social and emotional development of an individual. We hope to be able to better understand one’s level of emotional fitness, which can help us in developing relevant Programmes to equip youths and adults in succeeding the challenges of the 21st Century.

Identifying emotions of self

Identifying and labelling the emotions of self helps one to formulate and choose effective strategies for regulating them.13 Self-awareness includes the ability to accurately assess personal feelings, interests, values and strengths.14 Having the ability to monitor one's feelings and emotions, to discriminate among the different emotions experienced is important as it is information to guide one's thinking and influence the actions taken.2 Hence, individuals can appraise and express emotions accurately, and can quickly perceive and respond to their own emotions and better express those emotions to others. Individuals with this competence know what emotions they are experiencing and why they are feeling the way they feel. They are able to draw the links between their feelings and their behaviors. This component also helps individuals to recognize how their feelings affect their performance.15

Identifying emotions of others – emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence describes the ability, capacity, skill, or self-perceived ability to identify, assess, and manage the emotions of oneself, of others, and of groups. Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a type of intelligence that involves the ability to process emotional information and use it in reasoning and other cognitive activities.1 Emotional capabilities are conceptualized on a continuum from those that are at a comparatively lower level, for instance, performing basic, discrete psychological functions, to the more developmentally complex and work towards personal self-management and personal goals.16 Some of the abilities include: being able to perceive emotions in oneself and others accurately, using emotions to facilitate thinking, understanding emotions, emotional language, and the signals conveyed by emotions, and managing emotions to attain specific goals.1 People who possess a high degree of emotional intelligence know themselves very well and are also able to sense the emotions of others. They are affable, resilient, and optimistic.15

EI and understanding feelings

Empathy may be a central characteristic of emotionally intelligent behavior. Having higher EI promotes better attention to physical and mental processes.16 For instance, people higher in certain EI skills have higher accuracy in detecting variations in their own heartbeat—an emotion-related physiological response.17 They are also better able to recognize and reason about the emotional consequences of events.16 For example, higher EI individuals are more accurate in affective forecasting which is the in prediction of how a person will feel at some point in the future in response to an event.18 They are better able to empathize with the situations and feelings of others. This promotes compassion in order for one to be more tolerant of people with differing views. Being able to identify the emotions of others allows an individual to see a variety of emotions and identify potential cues about how they are feeling. This indicates an ability to understand how one’s actions can affect the emotions of others. Hence, the ability to discern the true feelings of others by understanding that everyone perceives the same situation differently and will experience different emotions.

EI and understanding social relationships

Studies have also showed that people with high EI tend to perform better in social setting, to have better quality relationships, and perceived as more interpersonally sensitive than those lower in19-22 Individuals can appraise and express emotions accurately and can quickly perceive and respond to their own emotions and that of others. These skills require the processing of emotional information from within the individual, for adequate social functioning.

Ability to cope with emotions - cognitive flexibility

The ability to cope with emotions is an important factor for individuals as they encounter different life situations. In trying to cope with emotions, cognitive flexibility is crucial in order to decide what behaviors to perform in negative situations.23 Cognitive flexibility is the skill of being aware of different options, and the openness to be flexible and adaptable in actions they choose to take.24 When individuals engage in harmful cognitive attributions, cognitive flexibility helps to enhance mental capabilities to respond appropriately with more apt attitudes and emotions.25

Emotional regulation - intentional behavior

Regulation of emotion may lead to more adaptive and reinforcing mood states. It involves the ability to deal with one’s emotions in productive ways, such as modifying them in different situations such that they help rather than impede the way an individual behaves. With this competence, individuals are better able to manage their impulsive feelings and distressing emotions well, stay composed, positive, and unflappable even in trying moments, maintaining a clarity of mind even under pressure.15

Neuroticism

Neuroticism refers to the tendency of an individual to be nervous and tense. Neurotic individuals are more prone to unpleasant emotions, such as fear, anger, guilt, sadness, and self- doubt. They often experience negative emotions, partly because of their tendency to worry more, to live up to their negative feelings and their lower reaction thresholds to aggravating situations.26 Emotional instability or neuroticism is related to personal anguish arising from inefficient problem-solving strategies.27 Individuals with high levels of neuroticism tend to behave impulsively without thinking twice. These subjective states can reduce emotional resilience of individuals and can have an impact on their ability to enjoy life and to cope with pain, disappointment, and sadness. Personality traits have been found to be a significant predictor of depression, high levels of anxiety, and irrationality as a response to stressful situations, making it particularly difficult for neurotic individuals to cope with stress effectively. Therefore, individuals with a high level of neuroticism are at greater risk of distress and depressive symptoms.28

Conceptualization and manifestation of Emotional Fitness Profile (EFP)

Overview

This study identifies the conceptualization and manifestation of the concept of emotional fitness. The Emotional Fitness Profile consists of a pool of 20 items that were generated based on the theoretical revised model of emotional intelligence developed by Mayer & Salovey, 1997.1 Participants answer each of the statements that describe several aspects of emotions and how they might feel or react depending on the situation. They will indicate to what extent each item best describes them. Each component of the profile was represented with four items.

Participants

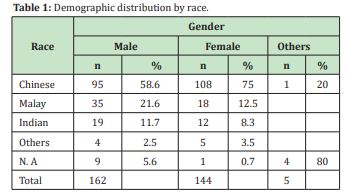

A total of 311 participants completed the questionnaire. The sample was made up of participants from a wide range of professions ranging from students to working professionals. Of those who reported their gender, 144 were females (46.30%), 162 were males (52.09%), and five prefer to not indicate their gender (1.61%). 204 participants identified as Chinese (65.6%), 53 as Malay (17.1%), 31 as Indian (9.97%), nine as Others (2.89%), and 14 who did not identify their race (4.50%). Table 1 below presents the gender and ethnic distribution of the sample.

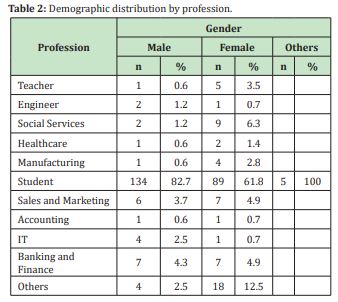

The demographic data pertaining to the profession of our participants indicated that five participants are teachers (1.61%), two participants are engineers (0.64%), 11 participants are in the social service industry (3.54%), four participants are healthcare workers (1.29%), five participants are in the manufacturing industry (1.61%), 228 are currently students (73.3%), 11 are in sales and marketing (3.54%), one participant is an accountant (0.32%), three participants are in the information technology (IT) industry (0.96%), 14 in the banking and finance industry (4.5%), and 22 as others (7.07%). The table below represents the gender and profession of the sample. This is represented in Table 2.

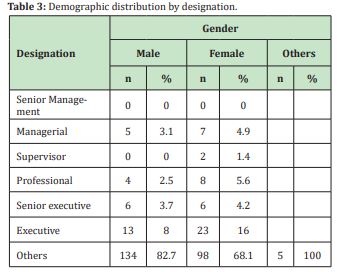

Of the population, 12 participants indicated holding managerial positions (3.85%), two participants indicated that they are supervisors (0.64%), 12 participants indicated that they are professionals (3.86%), 12 participants indicated holding senior executive positions (3.86%), 36 participants indicated holding executive positions (11.58%), and 237 participants indicated the option, others (76.20%) - which includes individuals who are currently unemployed or are currently students. The table below represents the gender and designation distribution of the sample. This data is represented in Table 3.

Procedure

Participants were asked to fill in their general demographic details, which collected the participant’s age, gender, race, nationality, designation, and profession. They will then complete the emotional fitness profile. The 311 participants rated themselves each on the 20 items using the five-point self- report profile assessed on five different components, each consist of four statements. The items on the EFP were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The questions were randomized for each participant to eliminate the possibility of order bias. The responses were screened to ensure that there are no incomplete responses.

For this report, the scores on the EFP are scored in an intuitive metric known as the percentage of maximum possible (POMP) scores.29 The POMP score is where the raw metric scores are linearly transformed into a 0 to 100 scale, where 0 represents the lowest possible score and 100 represents the highest possible scores. P. Cohen et al., (1999) stated that POMP scores are universal metric that makes it more intuitive for interpretation than scale scores with idiosyncratic ranges. In the EFP, the 1 to 5 metric score for each component was transformed into POMP score with this formula:

The minimum metric score for each individual component is subtracted from the total component metric score of each participant. This value is further divided by the difference between the maximum metric score and minimum metric score for one component. This calculated value is then multiplied by 100 to derive the normalized POMP scores.30,31

Measures of the five dimensions

The 20 items were conceptually grouped into five dimensions: Identifying emotions of self, identifying emotions of others, Ability to cope with emotions, Emotional Regulation, and Neuroticism.

Identifying emotions of self refers to the ability of an individual to identify and recognize one’s feelings and emotions

Identify emotions of others refers to the ability of an individual to understand and show sensitivity to emotional cues and listen well of the perspective of others

Ability to cope refers to the ability of an individual to manage their impulsive feelings and distressing emotions

Emotional Regulation refers to the ability of an individual to manage emotions under a wide range of situations, which includes processes directed towards positive and negative emotions that arise under normative, non-stressful circumstances.

Neuroticism: refers to the ability of an individual to control their emotional reactivity such as situations in handling negative emotions.

Data screening

When analyzing the responses, participants whose responses were incomplete were filtered out. The responses were screened to remove any participant who self-reported straight- line responses or left blank for any of the 20 items. At the end of the data collection, there was a total of 320 responses. However, only 311 of these responses were complete responses. Therefore, a total of 311 responses were suitable for analysis.

Internal consistency

After screening the responses, an internal consistency analysis showed Cronbach's alpha of 0.816 for the 20-items scale.

The high internal reliability suggests that the emotional fitness profile taps a single underlying construct. Identifying the five different components of the emotional fitness profile, each is internally coherent and can stand on its own.

The EFP is not without limitations, like most self-report measures, it can seem susceptible to faking the results. Thus, the EFP should not be used as a method for any diagnosis bearing in mind that characteristics and personality of individuals are highly susceptible to changes depending on environmental factors - situations that individuals are currently in or major life events that one recently experienced. In order for us to evaluate the validity of this profile, more data should be collected together with responses of participants from other assessments or scales. This can ensure that discriminant and convergent validity of the EFP are taken into consideration.

However, the EFP remains valid in assessing an individual who wants an appraisal on their emotional fitness. These individuals may want an assessment because they may wish to understand their own characteristics so that they can better set goals for themselves and work towards them. Furthermore, the EFP can help bridge the current gaps that exist in current Programmes by providing us with information to focus on specific components for our emotional fitness Programmes. This can further support, and guide individuals who experience problems in areas related to emotional fitness, to build a better emotional foundation.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Mayer JD, Salovey P. What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implication. Basic Books. 1997; pp. 3–34.

- 2. Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 1990;9:185–211.

- 3. Howe D. The Emotionally Intelligent Social Worker. Macmillan International Higher Education. 2008.

- 4. Tugade MM, Fredickson BL. Resilient Individuals Use Positive Emotions to Bounce Back From Negative Emotional Experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;86(2):320–333.

- 5. Cohen S, Syme SL. Social support and health. Academic Press. 1985; pp. 390.

- 6. House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social Relationships and Health. Science. 1998;241(4865);540–545.

- 7. Vandervoort D. Quality of social support in mental and physical health. Current Psychology. 18(2):205–221.

- 8. Kevern J, Webb C. Mature women's experiences of preregistration nurse education. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(3):297–306.

- 9. Lim N. Cultural differences in emotion: East-West differences in emotional arousal level. Integrative Medicine Research. 2016;5(2):105–109.

- 10. Tsai JL, Miao FF, Seppala E, et al. Influence and adjustment goals: Sources of cultural differences in ideal affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(6):1102–1117.

- 11. Matsumoto D, Ekman P. American-Japanese cultural differences in intensity ratings of facial expressions of emotion. Motivation and Emotion. 1989;13(2):143–157.

- 12. Lim J. The Big Read: With youths more open about mental health, it’s time others learn to listen-CNA. 2019.

- 13. Leerkes EM, Paradise M, O’Brien M, et al. Emotion and cognition processes in preschool children. Merrill Palmer Quarterly. 2008;54(1):102–124.

- 14. Denham SA, Brown C. “Plays Nice With Others”: Social–Emotional Learning and Academic Success. Early Education and Development. 2010;198521(5):652–680.

- 15. Serrat O. Understanding and Developing Emotional Intelligence. In O. Serrat (Edn), Knowledge Solutions: Tools, Methods, and Approaches to Drive Organizational Performance. Springer. 2017;pp. 329–339.

- 16. Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? American Psychologist. 2008;63(6):503–517.

- 17. Schneider TR, Lyons JB, Williams M. Emotional intelligence and autonomic self-perception: Emotional abilities are related to visceral acuity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(5):853–861.

- 18. Dunn EW, Brackett MA, Ashton James C, et al. On emotionally intelligent time travel: Individual differences in affective forecasting ability. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33(1):85–93.

- 19. Brackett MA, Warner RM, Bosco JS. Emotional intelligence and relationship quality among couples. Personal Relationships 2005;12(2):197–212.

- 20. Brackett MA, Rivers SE, Shiffman S, et al. Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: a comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(4):780–795.

- 21. Lopes PN, Salovey P, Côté S, et al. Emotion Regulation Abilities and the Quality of Social Interaction. Emotion. 2005;5(1):113–118.

- 22. Lopes PN, Salovey P, Straus R. Emotional intelligence, personality, and the perceived quality of social relationships. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35(3):641–658.

- 23. Alexander JK, Hillier A, Smith RM, et al. Beta-adrenergic modulation of cognitive flexibility during stress. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19(3):468–478.

- 24. Martin MM, Rubin RB. A new measure of cognitive flexibility. Psychological Reports. 1995;76(2);623–626.

- 25. Moore A, Malinowski P. Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition. 2009;18(1):176–186.

- 26. Izard CE, Libero DZ, Putnam P. Stability of emotion experiences and their relations to traits of personality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(5):847–860.

- 27. Clark LA, Ro E. Three-Pronged Assessment and Diagnosis of Personality Disorder and its Consequences: Personality Functioning, Pathological Traits, and Psychosocial Disability. Personality Disorders. 2014;5(1):55–69.

- 28. Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;96(3):465–490.

- 29. Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, et al. The problem of units and the circumstances for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1999;34(3):315–346.

- 30. Au WT, Wong YY, Leung KM, et al. Effectiveness of Emotional Fitness Training in Police. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. 2019;34(2):199–214.

- 31. Nam Y, Kim YH, Tam K. Effects of emotion suppression on life satisfaction in Americans and Chinese. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2008;49(1):149–160.