When referring to the issue of child sexual abuse, we are facing a situation of vulnerability for minors, who immediately require an interdisciplinary intervention that guarantees their emotional, physical, and social stability.

However, it turns out to be a challenge for professionals in psychology, to be able to discern between a real argument of the alleged victim and a false memory established by external factors in the minor. It should be clarified that this article never tries to question, revictimize or not consider as real the minimum manifestation of sexual abuse by any person. This article highlights the importance of professional expertise when assessing a minor who has revealed alleged abuse. Multiple studies and publications have been carried out that refer to the implantation of false memories or recollections in people. Therefore, a conceptual, methodological, technical, and ethical review of the discrimination of memories by professionals in psychology is necessary.

Keywords: Sexual abuse, Minors, Memory, Psychological expertise

Talking about memories, one must initially be clear about what is known as memory, which can be defined as the psychological process of encoding (shaping), storing (recording) and retrieving (remembering) the various events that occur throughout life whether these are positive or negative for the individual. Within the understanding of the phenomenon of memory we have two important dimensions, short-term memory or working memory, which allows us to retain information long enough to be used; Within the understanding of the phenomenon of memory we have two important dimensions, short-term memory or working memory, which allows us to retain information long enough to be used; and long-term memory, which allows information to be preserved in a lasting way thanks to coding, through this memory aspects such as learning are developed and information is linked with emotional components.

Thanks to the work of Tulving,1 three categories are structured in long-term memory, which are still in force:

- Episodic, related to a specific time and place. Linked to autobiographical aspects.

- Semantics, responsible for general knowledge acquired over time and not linked to any learning process.

- Procedural, cannot be consciously inspected. It is linked to motor activities.

It falls on episodic memory, the ability to retrieve information related to events in our lives; that stored information can be retrieved by images or words, later they will be transmitted when so decided. All this in people without physical, chemical, or psychological alterations that could alter the information of those memories.

From the above, Porras indicates.2

In the study of the retrieval process, it is also interesting to know the different ways of recalling the information available in memory; some of these are free recall, cued recall, and recognition. Using the free and cued recall modalities entails a double process: first, generate information elements that match the search criteria; this step is considerably simplified in cued recall since the number of options to be generated is reduced. Secondly, choose, from among the generated options, the one that we consider to be the appropriate response. In reconnaissance tasks it is not necessary to generate a set of options since these are already established for us and the job consists of checking each of these options to choose the one that we consider to be the appropriate option (p.32).

In short, to gain access to the memories of semantic memory, we find the possibility of free recall, in which a considerable effort is not required to evoke the information; while the memory with cues consists of the evocation after the presentation of some stimulus that is associated with the desired memory. While the evocation through recognition occurs by discarding options presented, until the memory or the necessary information coincides.

Considering the above, we can talk about how traumatic memory is processed in minors classified as alleged victims of sexual abuse, Pinchanski, Víquez and Zeledón3 point out, traumatic and non-traumatic memories before 20-30 months could be stored as implicit memories and with lack of narrative, at around two to three years of age, minors may be able to accurately report some personal experiences. However, it will always be complex for minors to retrieve information without the support of contextual signals or invitations, either by suggestive questions, by listening to the stories of others or by pressure factors.

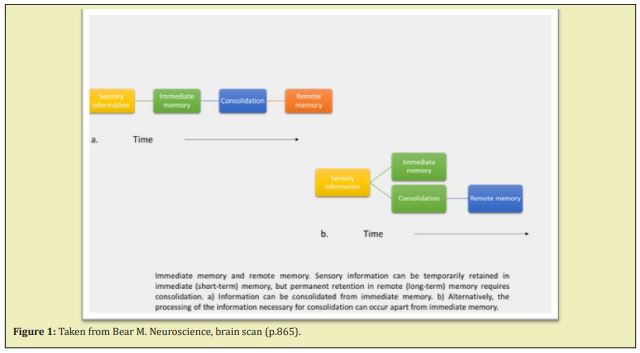

Now, it should be clear that every cognitive process (thought) in human beings will have flaws, when talking about the memory process, this should not be considered as a one hundred percent rigid and reliable hard drive, since there are "cuts” to this information, to reality, which are edited to give them meaning, this meaning arises from subjectivity, the usefulness of the cognitive maturity of the individual who retrieves the information. Bear4 indicates, pointing out that sensory information is established in short-term memory, understanding this, when an event with emotional impact arises, this information is consolidated in short-term memory, however, time enters at stake, occupying an indispensable role in the consolidation of information Figure 1.

Based on the above, remembering a sexual abuse will never be the same as remembering a normal or non-threatening event, since, when recalling the events, they can be perceived as distant, as something observed from afar, even a difficulty to order them chronologically, this from the research developed by Bass5 in relation to traumatic memories in minors. The theoretical position continues indicating that cognitive development and socio-family support will always influence the processing and chronological order of information and in the possible biases that may occur (scripts without connection, incomplete, contradictory).

If false memories are explored, reference should be made to multiple studies, for example, in 1990 in Oregon, the FMS (False Memory Syndrome Foundation) was created, which has worked on various investigations, demonstrating how the recovery of memories is affected by two basic components, the suggestion (given by other people about the event or alleged event, especially if these people are significant, which generates a false memory with a high emotional component due to the suggestion given), the time elapsed between the event and the narration or revelation of the itself (which "contaminates" the original information and can be distorted over time, therefore, the longer this period, the more likely that the memory is manipulable or contradictory).

The psychologist Elizabeth Loftus6 indicates, being a pioneer in the study of false memories, the easy manipulation of memory has been demonstrated through her research, which has forced a re-interpretation for the judicial systems of everyone, essentially because they pointed out that memories can be distorted without the person realizing it, especially if they are a minor and the first-hand information given by witnesses and victims does not have to be 100% reliable. This meant that the resource of assessing the veracity of the story and its content with material evidence was deemed necessary.

On this point, as Saborío and Víquez7 point out, in a study carried out in the Department of Legal Medicine of the Costa Rican Judiciary, when evaluating the credibility of a report by a minor victim of alleged sexual abuse, should be considered:

- a. General Characteristics, evaluate the credibility through the story, logical consistency, details, clarity of the alleged and the description of incidents.

- b. Specific Contents, assess the specificity of the story in relation to the event, detailed identification of the alleged offender, coherence to the context in the story, description of the interactions and their content.

- c. Peculiarities of the Content, this aspect must include guilt for the consequences on the accused.

- d. Content Related to Motivation, aspects related to the impulse of the alleged victim to report the abuse that occurred, considering the detection of doubts about the testimony and spontaneous corrections.

- e. Indicators of Sexual Abuse, considering vulnerability, retraction due to fear and whether there is a motivation to lie.

According to the above, the possibility of a traumatic event, such as sexual abuse, being implanted in the memory of a minor is high, if their cognitive structure has not reached its maturity level and they have an innate predisposition to suggestion, through significant persons or the persons in charge of their assessment or intervention.

The term trauma is defined as a psychological response to one or several events that, outside of the everyday environment, generate an emotional, cognitive, and behavioral imbalance; due to the high level of stress that the event has caused. In this way the trauma becomes a sequel. Echeburúa and Amor8 mention that "any traumatic event (sexual assault, torture, chronic violence at home, the murder of a father or mother, the suicide of a loved one, etc.) supposes a bankruptcy in a person's feeling of security and a basic loss of trust in other people” (p.2).

Now, the effect of a traumatic event on the memory process of the human being has been studied at different times, in this case the position of Echeburúa and Amor8 continues, who indicate in their study that "the identity of victim in perpetuity (installation in suffering or victimhood), with a permanent status, is counterproductive because it prolongs the mourning of the afflicted and limits them to start a new chapter of their lives (p.9).

From the foregoing, it should be emphasized that a minor, who has suffered violence (as is the case of sexual abuse), will develop a series of traumatic sequelae due to the emotional impact that the episode symbolizes, for example, indicate Echeburúa and Corral9 that at least 80% of the victims suffer negative psychological consequences. The scope of the psychological impact will depend on the degree of blaming the child by the parents, as well as the coping strategies available to the victim. In general, girls tend to present anxious-depressive reactions; children, school failure and unspecific socialization difficulties, as well as aggressive sexual behavior (p.4).

Therefore, if a minor has truly suffered sexual abuse, his memory establishes a trauma and therefore various emotional, psychological, and behavioral manifestations will be evident. Not just an empty or automatic narrative. However, the challenge arises to document these manifestations objectively and not be limited to the story of adults or caregivers of the minor.

A crucial factor in the discourse or disclosure of alleged sexual abuse of minors is the role of parents and/or caregivers as indicated by Pereda and Arch10.

In a later work, Faller, after conducting a study on the possible false reports in cases of child abuse detected by social service workers, establishes that the intentional false report is situated in 6% of all cases of sexual abuse. None of these cases was intentional on the part of the minor, rather the false reports came mainly from non-custodial parents (15%) (p.4).

In this way, it should be emphasized that minors relate bonds of protection and trust with their main caregivers, which makes them vulnerable to suggestion, as mentioned in previous sections. In this way, the influence of adults in the revelation of abuse and in the construction of the story in minors should be carefully analyzed.

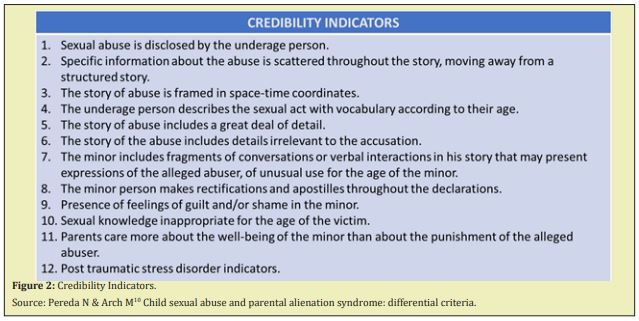

Continuing with Pereda and Arch,10 a series of credibility indicators are proposed before the story of an alleged sexual abuse in minors, as shown in Figure 2, the naturalness of the minor should always be considered when revealing this information, analyze the content of his speech, the language, and its emotional charge. This becomes an additional challenge for the professionals in charge of evaluating the story.

In addition, the intentionality of the adults around the minor must be analyzed; in a protective ideal, they should focus on the integrity of the minor and their well-being; however, many adults carry with them the intention of revenge (not associated with the alleged abuse) or the desire to obtain secondary gains from these processes.

From the above, Ruiz (2004) points out that the motivations or secondary gains of adults in these processes are diverse, beyond obtaining custody or interfering in compliance with the visitation regime, manage to remove the father from his life and that of his children, a revenge for a narcissistic wound of abandonment, including economic interests (p.157). Aspects to be considered during the collection of information.

As has been seen, this phenomenon has several challenges for those who oversee evaluating minors. Jiménez and Martín11 point out that the main resource will always be the interview and observation, as it should focus on:

- Previous history of the minor, intellectual level, memory, ability to interpret situations, to relate concepts and structure narratives, level of knowledge in sexual matters, language and vocabulary level, affective tone, emotional involvement, etc.

- Possible reasons for falsifying the statement: Possibility of pressure on the testimony of the minor for different reasons, or inadvertently, inadequate questioning or incorrect use of support material (for example, anatomically accurate dolls) (p. 92).

In this way, the professional in psychology must not only focus on the story of adults or minors, but also manage to investigate aspects related to the link with the alleged offender, link with caregivers, emotional burden of the event, signs of trauma, language used, and related cognitive and behavioral components.

In addition, we find Jiménez and Martín11 indicating that the questions must be formulated in a direct and simple way, avoiding negative forms. The vocabulary must be understandable to the child and leading questions must be avoided to guarantee genuine information. It is necessary to observe and assess the minor's level of knowledge about sexuality (p.91).

Fundamental aspects to guarantee an environment of trust and a speech as transparent as possible by the minor during the evaluation process. Factors that at the same time favor the psychological state of the minor, by not re-victimizing or blaming; without neglecting the technical criteria of the professional in charge, who must additionally analyze the veracity and credibility of the facts.

On the other hand, psychometric evaluation instruments can be used, which will support the findings of the interviews and professional technical criteria, such as those compiled by Pereda and Arch12:

- 1. Statement Validity Assessment (SVA).

- 2. Criteria-Based Change Analysis (CBCA).

- 3. Forensic Evaluation Protocol.

- 4. NICHD Investigative Interview Protocol.

- 5. Child Abuse Interview Interaction Coding System (CAIICS).

- 6. Child Sexual Abuse Interview Protocol.

- 7. Structured qualitative evaluation of expert testimony (SQX-12).

Together with these instruments and any other that contains a technical validity in the expertise carried out, the human factor can never be separated from the professional, in this case the assessment processes must always be approached with empathy and objectivity.13-18

Sexual abuse will always be a complex and delicate issue, especially when dealing with minors. As has been analyzed, a complex challenge is the presence of false testimony or false memory when declaring these facts.

The characteristics of these memories must be analyzed in detail, never affirming their truthfulness at one hundred percent, but neither affirming their falsehood at one hundred percent, for this the expert professionals will make use of the various necessary psychometric and forensic tools, which will give the courts a necessary technical support for decision making; taking into account the assessment of the story, its consistency, content and coherence; in addition to how it is maintained over time.

The integrity of the minor must always be guaranteed, avoiding re-victimization, blaming and other aspects that could alter their confidence and psychological state; however, the role of caregivers or parents in handling the revelation of the alleged abuse and the dynamics around it should also be analyzed.

The traumatic effect of sexual abuse should never be minimized; therefore, it will depend on the technical ability of the evaluating professional to maximize resources, handle information ethically and provide an environment that protects the integrity of the underage person being evaluated.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Tulving E. Episodic and semantic memory. Organization of memory. New York: Academic Press. 1972; p.381–403.

- 2. Porras Truque C. Contribuciones de la atención y el funcionamiento ejecutivo a la memoria episódica en jóvenes con consumo intensivo de alcohol. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. España. 2016.

- 3. Pinchanski Fachler S, Viquez Hidalgo EM, Zeledon Grande CM. Memorias impuestas. Med leg Costa Rica. 2004;21(2):07–20.

- 4. Bear M. Neurociencia, la exploración del cerebro. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia, Estados Unidos de Norteamérica. 2008.

- 5. Bass E, Laura D. El Coraje de Sanar. Editorial Urano, Barcelona- España. 1995.

- 6. Loftus EF. The price of bad memories. Skeptical Inquirer. 1998;22:23–24.

- 7. Saborío C, Víquez E. Myths concerning forensic psychological assessment in child sexual aggression cases: The need of a change of paradigm. Medicina Legal de Costa Rica. 2006;23(2).

- 8. Echeburúa E, Amor Pedro J. Memoria traumática: estrategias de afrontamiento adaptativas e inadaptativas. Terapia psicológica. 2019;37(1):71–80.

- 9. Echeburúa E, Corral P de. Emotional consequences in victims of sexual abuse in childhood. Cuadernos de Medicina Forense. 2006;(43-44):75–82.

- 10. Pereda N, Arch M. Abuso sexual infantil y síndrome de alienación parental: criterios diferenciales. Cuadernos de Medicina Forense. 2009;58:279–287.

- 11. Jiménez Cortés C, Martín Alonso C. The testimony assessment on sexual abuse on children. Cuadernos de Medicina Forense. 2006;(43-44):83–102.

- 12. Pereda N, Arch M. Exploración psicológica forense del abuso sexual en a infancia: una revisión de procedimientos e instrumentos. Papeles del Psicólogo. 2012;33(1):36–47.

- 13. Díaz de León M, Basilio A, Briones J. Trauma: un problema de salud en México. Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología. México. 2016.

- 14. Loftus EF. Creating False Memories. Scientifi c American. 1997;277(3):70–75.

- 15. Loftus EF. Leading questions and eyewitness report. Cognitive Psychology. 1975;7:560–572.

- 16. Mapua F. The Neurociencie of Addictions. Cambridge University Press. University of Cambridge. 2019.

- 17. Saborío C. Estrategias de evaluación psicológica en el ámbito forense. Revista Medicina Legal de Costa Rica. 2005;22(1).

- 18. Tejedor MPR. Credibilidad y repercusiones civiles de las acusaciones de maltrato y abuso sexual infantil. Dialnet. 2004;4(1-3):155–170.