The asymmetric construction of gender roles in the Brazilian society contributes to the fact that, currently, women's experiences in the university environment are marked by gender bias. This situation was aggravated by the pandemic. The present research aimed to evaluate the dynamics of pleasure and suffering in the academic work of undergraduate psychology students at the University of Brasília, Brazil, as well as to identify the main strategies used by them to face it. The theoretical-methodological perspective adopted was the psychodynamics of work and female work. The research is characterized as descriptive, quantitative and qualitative. The Work-Related Injury Scale was applied to 196 female students and eight focus groups were held, with an average of 4 (four) participants each. As a result, in the quantitative stage, it was found that, in the three factors of the scale, a median result was obtained, which means a state of alert regarding the harm and psychosocial risks related to work. In the qualitative stage, six categories were identified: "Being a woman and being a student", "Intersections of suffering", "Impact of the pandemic at work", "Collective mediation strategies", "Individual mediation strategies" and "Socio-professional relationships". The results are discussed considering that women still have to deal with the triple workload overload, and that they do not feel safe to freely occupy the university environment, implying the need to promote more institutional listening and welcoming spaces, so that it is possible to build strategies to transform the organization of work. Short-term actions are recommended so that the alert state in relation to risks at work is not aggravated.

Keywords: Female work, Suffering, University female students, Intersectionalities, psychodynamics of work, Pandemic

Historically, due to an asymmetric construction of gender roles in Brazilian society, female education was mostly focused on domestic care activities. Thus, only in the 1960s did women actually have access to higher education institutions.1 Therefore, the presence of women in academic environments is recent, when compared to men, which is a reflection of gender biases that mark the experiences of women in this country’s society.

In an integrative review study on psychological distress in university students,2 it was found that there is a strong association between female gender and the incidence of common mental disorders (such as anxiety and depression) in students. In this way, female university students are more likely than male ones to suffer psychically, which reinforces the hypothesis of the gendarmation of experiences in the academic environment.2 Despite this, there is a lack of research aimed at investigating the experience of students, taking into account gender issues,3 especially from the perspective of the psychodynamics of work.4

The activity of studying, despite not being characterized as an employment relationship, is configured as a job. According to Dejours,5 work is characterized by its ability to transform the worker and the production of a final result. During the university period, students are constantly prescribed activities that require cognitive, affective and temporal investment and that promote the development of new skills.4 Furthermore, the fact that education is one of the main means of social ascension in our society brings an emancipatory character to the study.6 Thus, it is possible to affirm that studying not only promotes production, but also the cognitive, affective and social transformation of students.

According to the psychodynamics of work, an approach that studies the relationship between work and mental health, suffering is inherent to work.5 In view of the fact that when work activities are being performed, there is a gap between what was prescribed and what actually occurs in the workplace. Hence, suffering is born from this constant confrontation between the individual and the real work. However, this suffering may or may not lead to the development of pathologies depending on how people face it and how work is organized.5,7

When workers perform and are recognized for activities that make sense to them in an environment that favors the development of cooperative interpersonal relationships and that allows the subjective mobilization, suffering can turn into pleasure, through the construction of creative coping strategies, which allows the construction of healthy experiences at work. However, when the labor environment does not have these characteristics, and the defensive strategies created by the workers generate some type(s) of damage to their health, the suffering at work is increased, which can lead to physical and mental destabilization of the person and, thus, to the development of pathologies.7

Studies carried out with post-graduate students8,9 showed that a significant source of suffering for them is the overload of prescribed activities, which can lead to physical and mental exhaustion. With regard to female students, it is hypothesized that this suffering from the overload of academic demands may be increased by practices and consequences of gender violence, which, as something that structures Brazilian social relations, can often be reproduced by policies, employees and students from educational institutions.

However, for many college students, the suffering experienced in the academic environment is not enhanced only by gender relations, but also by other factors, as demonstrated by Oliveira, Nunes and Antloga4 and by Sousa and Sousa,6 in studies that describe the suffering of black students and low-income ones, respectively, in higher education institutions. According to the transdisciplinary theory of intersectionality, understanding the extent of complex forms of oppression is only possible through an integrated approach, which may include, in addition to gender, race and class relations, other types of relations, such as those of sexuality.10 Therefore, this study also intended to explore the influence of other social relationships on female students' suffering.

In addition to all these factors mentioned, the pandemic triggered by COVID-19 appears in 2020, as well as the measures of social distancing and suspension of activities (including the ones at colleges) that were decreed to reduce the contamination rates. In this context of uncertainties and risks, there is an increase in negative emotions, such as fear and anxiety.11 Furthermore, Maia and Dias12 found that the depression, stress and anxiety indices of Portuguese university students enhanced significantly in the first year of the pandemic, compared to scores obtained in 2018 and 2019, so it is believed that this pandemic scenario also had a significant impact on the health of Brazilian students.

In view of the concepts of the psychodynamics of work, we aim to study the suffering experienced by female undergraduate students of psychology at the University of Brasília (Brazil) during the confrontation with the reality of work, in the context of the pandemic caused by COVID-19, as well as the defensive strategies used by them to face it.

Participants

In accordance with the objectives of the present study, the public was defined as female undergraduate students of psychology at the University of Brasília, enrolled as regular students and who had been studying from the second semester of the program on. We opted for descriptive research, with the objective of describing the phenomenon in the most detailed way possible. However, in order for the suffering of female undergraduate students to be understood in the best possible way, a project with two stages was chosen: a quantitative and a qualitative one.

According to the 2018 Statistical Yearbook of the University of Brasília, there were, on average, 464 female active regular students registered in the undergraduate psychology program. However, as, according to the yearbook, approximately 73 of them were freshmen, and the instrument that was used requires the person to have at least 6 months of contact with the work environment, to obtain a representative sample of this population, it would be necessary that, at least, 195 students answered the Work-Related Injury Scale, considering a margin of error of 5%. Therefore, for the quantitative stage of this research, 196 participants were obtained.

Considering the research sample, it is possible to state that the prevailing sociodemographic profile of the participants consists of female students aged between 18 and 24 years (85.7%), with a monthly family income between three and six minimum wages (17.9%) or between nine and twelve (17.9%), identify themselves as white (53.6%), cisgender (99%), heterosexual (45.4%); agnostic (28.1%), are dating or in a non-marital relationship (42.3%); spend between 2 and 6 hours a week on housework (49.5%), do not have to frequently take care of an elderly person (83.7%) and do not have children (94.9%).

Instruments

First, as a quantitative source of data collection, the Work-Related Injury Scale (WRIS) was used, which originally belongs to the Work Psychosocial Risk Assessment Protocol, created by Facas.7 For this research, we opted for the updated version by Facas and Mendes.13 This scale refers to possible damage that the worker may suffer due to the confrontation with the work context and is divided into three factors: psychological, social, and physical damage. To assess each item, a five-point Likert scale was used. According to the interpretation proposed by the authors, the results of the scale assess whether work-related harm consists of a low, medium, or high risk for the psychosocial health of workers.

Then, as a qualitative source of data collection, focus groups were carried out, which, according to Vegas and Gondim,14 allow the understanding of the construction of perceptions, attitudes and social representations of human groups about a specific topic. In this method, the researcher acts as a moderator, by stimulating and coordinating the discussion of a group of people about a given topic, so that the dynamics of these group interactions allows discussions to reach a level of reflection and problematization that other techniques do not achieve.15

It is recommended that at least two groups be organized for each topic considered relevant to the theme in question in the research.15 Therefore, in this study, this technique was chosen in order to generate discussions on the perception of students in relation to the suffering experienced in the workplace, based on a script composed of four main topics: gender-related discriminations, discriminations related to other social relationships, ways of coping, and implications of the pandemic on mental health. Thus, eight focus groups were carried out, with an average of 4 (four) participants each.

Procedures

It is important to emphasize that both the application of WRIS and the conduct of focus groups occurred remotely, due to the COVID-19 pandemic scenario. Participants were recruited through posts made in Whatsapp groups, Facebook and Instagram pages of various students, research groups, and academic centers, which contained a link to access the online form (Google Forms) for registration in the survey. This form initially presented the main objectives of the research, explained the confidentiality of the data collected and voluntary participation, in addition to providing the research contact email and the prerequisites for participation. After the participant's confirmation that she had read and agreed with the terms of participation in the research, she was directed to the next page of the form, which contained the Work-Related Injury Scale (WRIS)13 and then, the items of the sociodemographic questionnaire. Finally, a small paragraph was placed informing the importance of the qualitative stage of data collection, as well as a space to fill in, not mandatory, so that the participants could provide their contact information if they wanted to be part of the focus groups.

Once the names, telephone numbers, and emails of the students who showed interest in participating in the focus groups were collected, they were contacted via Whatsapp, and then, were presented with the Informed Consent Term (ICT) (annex 1) regarding this second stage of the research. Then, taking into account their availability of time, as well as their sociodemographic characteristics, the eight groups were scheduled and held via the Google Meets videoconference platform, with an average of 1 (one) hour and five minutes each. It is noteworthy that the sociodemographic variables were taken into account in order to build groups whose participants had characteristics as diverse as possible, so that the discussions would be richer. During the conduct of the groups, the research team was composed of two people: one responsible for stating the questions and moderating the participants' responses, while the other took note of the main points spoken by them, as well as recorded the group.

Data analysis

The data collected by the sociodemographic questionnaire and by the WRIS, after going through a database cleaning, where duplicate responses were excluded, were analyzed in the Statistical Package for Social Science - SPSS software (version 2.5). Thus, the main descriptive statistics of the items and factors of the scale (mean, standard deviation and variance) were obtained, as well as the frequencies of the sociodemographic variables.

Regarding the data from the qualitative stage, thematic categorical content analysis was performed. According to Bardin16, the analysis must follow three stages: pre-analysis, material exploration, and treatment of results. In the first, the transcription of the recordings of the focus groups was carried out. In the second, each of the eight corpuseswas analyzed individually by the three researchers and, after a general reading and marking of the registration units (themes), based on the recurrence and relevance criteria, they were jointly defined. the categories, with the help of the guiding teacher. Finally, in the third, the results were treated through inference and interpretation.

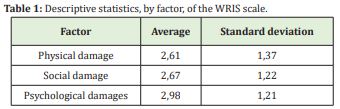

The means and standard deviations of the three factors of the Work-Related Injury Scale (“Physical Harm”, “Social Harm” and “Psychological Harm”) are shown in table 1. When analyzing them, it is important to emphasize that the value minimum was 1 (one) and the maximum was 5 (five), in addition to considering that the scale is negative. Hence, the higher the score obtained, the greater the psychosocial risks to the health of the workers:

According to the interpretation of the scale proposed by Facas and Mendes,13 the results found in all three factors represent an average risk (values between 2.30 and 3.69) for the health of the female students, characterizing as a situation of alert to the possible damages arising from the work environment, and that demands interventions in the short to medium term. However, it is noteworthy that, despite the results for the three factors being placed in the same category of analysis, the average of the "Psychological Damage" factor had the highest scores, which indicates that the psychic dimension of the damage should be analyzed with more attention than the others.

In the qualitative stage, from the thematic categorical analysis proposed by Bardin,16 where recurrence and relevance criteria of the themes were used, the following categories were identified:

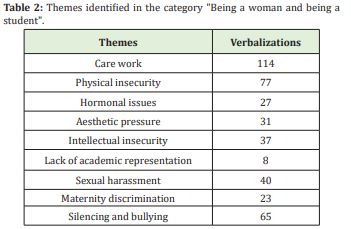

Being a woman and being a student

In this category, students reported suffering from the overload of domestic activities they have to perform at home, which accumulate with the demands of the course, hence they are always tired and rushing to take care of everything. Furthermore, the students who are also mothers expressed considerable indignation at the discrimination suffered at the university. Participants also mentioned the difficulty in dealing with hormonal changes and disturbances while living in a production logic that ignores that women go through this monthly. When remembering the pre-pandemic time, when the activities at the university weren’t suspended, they mentioned insecurity when walking around the campus, especially at night and if they were alone, as they felt vulnerable to possible attacks. In the context of remote teaching, suffering from the pressure and judgments to always be beautiful when turning on the cameras was reported. They also identified that their voices are silenced, questioned and belittled. Finally, they expressed discomfort when studying mostly theories and texts written by men, since these theories often present an erroneous view of femininity (Table 2).

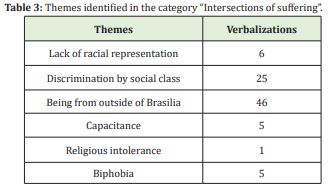

Intersectionalities of suffering

The students reported a lack of racial academic representation, questions about being from outside Brasilia, discrimination for reasons of class, capacitation, religious intolerance and biphobia. Thus, the category brings the intersectionalities of suffering linked to the themes exposed (Table 3).

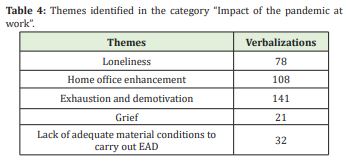

Impact of the pandemic on work

The category demonstrates the students' verbalizations about the impacts of the pandemic at work, seen here as the students' study. Their speeches are surrounded by these impacts, as it is inherent to mention them, having as a panorama the experienced moment. The most mentioned themes were loneliness, the fact that the home environment has become the same for different times, the intensification of domestic activities, seen as the intensification of the home office, exhaustion, lack of motivation, grief and the lack of adequate materials for the realization of distance learning (Table 4).

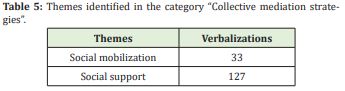

Collective mediation strategies

To deal with the suffering at work, female students reported using the following support networks: family, friends and romantic relationships, with an emphasis on people who welcomed their feelings and who had at least some experiences similar to theirs, so that there would be greater recognition of the pain felt, as well as sharing of the strategies used to deal with that suffering. The organization and social mobilization was also mentioned as a way to deal with this suffering, referring both to the organization of the class, as a collective, to take demands to the teachers and the coordination regarding the engagement in groups and conversation circles (Table 5).

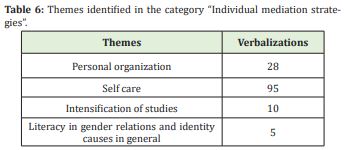

Individual mediation strategies

The students reported the use of personal organization as a strategy to face academic and personal demands, such as the use of planners and diaries and the separation of a specific time for each aspect of life. Self-care was the most reported strategy, including exercising, investing in hobbies, therapy, taking advantage of solitude, eliminating negative elements, setting limits, focusing on positive thoughts and activities, and self-regulatory practices. In addition, they also reported an intensification of studies aimed at improving their confidence and literacy on gender issues and other social relationships to become more aware of their place of suffering and its causes (Table 6).

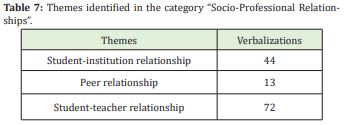

Socio-professional relationships

Regarding socio-professional relationships, the students reported positive and negative aspects in each relationship. In peer relationships, they reported a pressure for productivity from the students, generating the feeling of insufficiency, but also, strong support and union to resolve conflicts with teachers. In the relationships between students and teachers, excessive workload imposed by those, lack of understanding, discrimination and inability to resolve conflicts were reported, often requiring recourse to the course coordination. However, in a smaller amount, they reported on the support and reception given by certain teachers. In the relationships between students and the institution, many did not know how to appeal or did not feel comfortable to appeal, while some appealed and had positive (supportive) or negative (failing to resolve their questions) results (Table 7).

In the category “Being a woman and being a student”, the theme with the highest number of verbalizations was “care work”, referring to household activities such as cleaning the house, preparing food, caring for children or other family members. In this way, its high recurrence corroborates what was exposed by Antloga, et al.18 and by Vieira and Amaral,1 in regard to the compulsory and naturalized assignment to women of jobs in the domestic sphere that are related to care, thanks to a highly restricted and engendered sexual division of labor that was consolidated with the advances of capitalism.18 As a result, women who perform productive work, that is, who "work outside the home", have to, as one of the research participants said, "be always running, always studying, and taking care, and helping a younger brother, helping the family, and mixing the study time with activities at home”, which generates an overload of demands, physical and mental fatigue, in addition to other psychosocial damage. Therefore, it is characterized as a source of suffering.

According to the 2018 University of Brasília statistical yearbook, more than 70% of regular students enrolled in the psychology course were female. However, even with this context of mostly female presence in the course, it appears that the university environment is not yet organized to accommodate the specifics of the female experience and, in many aspects, it seems to have not made the necessary adaptations to serve a diversified public. The fear experienced by the female students of suffering some type of sexual violence in the university environment or on the move from their home to there, the silencing of their opinions in the classroom, whether by male students or by teachers, the invisibility of hormonal issues, the lack of flexibility of institutional and teacher policies in dealing with students who are mothers, the rare inclusion of contributions by female authors when dealing with historically important theories, as well as the lack of perception of institutional support to address issues of harassment are clear indicators that university was designed to meet male demands. Thus, the speech “I wonder a lot if the academic environment is for me, if I should be there” significantly represents the psychic consequences of this organization of work for female students.

The category “intersections of suffering” had as its main verbalization the theme “being from outside Brasilia”, with 46 quotes made during the focus groups. The theme is characterized as the difficulty that students from other states have found in adapting to a new city, especially with regard to making new friends, staying away from family and the discrimination suffered in relation to accents. In an article on the mental health of university students, Vizzoto, Jesus and Martins19 measured that students who left their family home to attend college had higher levels of anxiety, stress and depression compared to those who did not leave, which dialogues with the results of this research. However, it is noteworthy that the focus group participants emphasized the suffering related to the difficulty of forming significant bonds with people in Brasília, and not just the distance from the family.

The second most recurrent theme in this category can be described as discrimination, directly, indirectly, structurally or institutionally, suffered by the most vulnerable social classes within the university, considering that from the participants mentions “UnB is frequently made for a specific type of person, right? And, if you are a little out of it, you will inevitably have a type of suffering ”. Thus, it corroborates what Graner & Cerqueira (2019) had already pointed out about discrimination by class at the university, which reflects the Brazilian sociocultural context.

The other themes in this category also obtained verbalizations about the lack of racial representation, which refers both to the suppression of academic references of non-white and non-European people and the lack of identification with other people in the course, as can be seen in the statement "when we turn on the camera, when the collective calls, I realize that it's a very white course, you know, with a very standardized color, it doesn't have a very nice diversity”. This suppression of literature is characterized as epistemicide, and implies the invisibility of knowledge of the non-white population, and the specifics of their experiences, so that it also emerged as a source of suffering for black students in Oliveira, Nunes and Antloga.4 Regarding the little diversity in the course, this non-identification with others can lead to feelings of not belonging in that academic environment, as commented by some participants, which also involves significant psychological distress. In addition, this category also contains speeches about capacitation and how the forms of bullying are felt, as explained in the speech "the bullying I had, was the class that reported it, because I did not realize that the person was playing a mean joke or did not understand. I'm learning now”, and, finally, about religious intolerance and biphobia.

It is important to emphasize that the low number of verbalizations of some themes in this category is related to the sociodemographic profile of the research participants, who were mostly white, cisgender and heterosexual women and, among those who made up the qualitative phase, only one I had the experience of being a person with a disability. Thus, considering the affective mobilization that the speeches related to these topics generated in the groups, as well as the meaning they have, the choice was made to characterize them as themes in the content analysis.

The category “impact of the pandemic at work” had as its main verbalization the theme “exhaustion and lack of motivation” with 141 citations during the focus groups, and a large number of citations also on the theme “intensification of the home office”, with 108 verbalizations. The themes were feelings of tiredness, both physical and mental, lack of motivation in relation to the demands of college, anguish and anxiety generated both by the uncertainty and fear caused by the pandemic situation, as well as the intense work done at home and the potentialization of family life on account of quarantine decrees during the pandemic. In this way, the home environment has also become a workplace, which can lead to an overload of activities, as one of the participants quotes: “one thing I saw a lot of people talking about, like, is that you do everything in the same environment , then your leisure, your rest, your work, everything there, then how do you differentiate what you are doing, right” . In this sense, the participant's reports are in accordance with what Malloy-Diniz and collaborators (2020) recently presented about how the pandemic and all the issues linked to situations of social distancing can affect the mental health of each person, with a view to intensification of the home environment.

The verbalizations about loneliness were also very significant, highlighting the links and contacts that were lost with the emergency change to distance learning, since many informal spaces for interaction between students do not exist in the remote model. Furthermore, this feeling of loneliness was heightened in the case of students who entered university in 2020, as they had little or no contact with their colleagues before the pandemic and, thus, many feel that they do not know the people they study with, since they only see screens.

The other topics in this category, mourning and the lack of adequate material conditions for distance learning, also caused significant mobilizations among students. The transition to the remote model implies adaptations in the home environment, to make it suitable for study, since, before the pandemic, many students had the habit of studying predominantly in the university space. There was an increase in spending on the internet, purchase of more comfortable chairs, headphones, among others, which, in turn, may reflect the way in which the relations of socioeconomic inequality permeate the students' experiences, since not all students have material conditions to cover these expenses or have adequate space at home to turn into a home office , as mentioned by one of the participants “I even cried a few times because I wanted to be watching class and the internet kept failing a lot (...) .) this issue of inequality ends up stressing me”.

In individual strategies to deal with suffering, there were more reports of personal organization and self-care. Personal organization allows students to set specific times for each activity and respect their moments of leisure and indisposition, understanding that the line of disposition is floating and non-linear. The self-care reports were diverse, but the most significant were those centered on self-knowledge, how to recognize their limits, without blaming; the elimination of sources of suffering, such as the constant connection with negative news and contact with people who reinforce these anxieties; and the focus on positive experiences, both in doing what you like and living today, valuing the little things. Defensive strategies emerge as a buffer to alleviate organizational pressures in the work environment and prevent illness due to the impossibility of mobilization.8,9 Thus, the statement "I think you either go crazy or start to value everything" represents the need to seek such strategies, given the paralyzing scenario of the pandemic.

In collective strategies of suffering, there is an almost four times greater recurrence of the topic “social support”, in relation to “social mobilization”. Mobilization strategies, within the psychodynamics of work, are those that allow the transformation of suffering into pleasure, mainly through the construction of spaces for public discussion and deliberation, as well as the establishment of cooperative relationships between peers.20 In this sense, from the students' discourse, there is a lack of institutional spaces that promote this collective organization of them, especially with regard to issues included in the first category of analysis, so that most of the verbalized mobilizations referred to initiatives that came from the students themselves, such as conversation circles held by the academic center and sponsorship dynamics, similar to what was found by Oliveira, Nunes and Antloga.4

In the category "socio-professional relationships", the most frequent theme was the student-teacher relationship, with many negative reports about the overload resulting from the high demand for tasks and readings and the issue of conflicts between work groups without the support of teachers, but also , mainly on harmful behaviors, such as the rejection of doubts, the lack of understanding of the experiences of students related to COVID-19 and adaptations to EaD, and even the expulsion of a mother with her child from the classroom. Due to all these issues, the students report feeling that what is studied in the psychology course is only in theory and is not applied in practice, as one of the participants points out: “and a psychology professor is not that flexible, guys. Oh, sweet illusion” . However, of the students who turned to the institution to resolve these issues, most reported getting support, however, the vast majority did not appeal, often not knowing how to do it and who to talk to.

Finally, it is noteworthy that, in all categories of qualitative analysis, it is possible to draw dialogues between the themes found and the results of the Work-Related Injury Scale. In this sense, all these sources of suffering mentioned (impact of the pandemic, experience of gender at the university and intersectionalities) have physical, social and psychological consequences in the health of students, influencing their sleep patterns and the frequency of pain feelings, for example, as well as how they relate to the people around them and how they perceive themselves. Thus, there is a reflection of these complex sources of suffering in the health alert status of students, in relation to work-related biopsychosocial damage, which is characterized as a scenario where, if health promotion interventions are not made, it can lead to a picture of pathogenic suffering.

The fact that women still have to deal with the overload of the triple workday is problematized, and that they don’t feel safe to freely occupy the university environment, which implies the need to promote more spaces for listening and institutional care, so that the collective mobilization of students is possible and, thus, the construction of strategies to transform the organization of work, and the alert situation of their health can be alleviated.

Furthermore, the limitations of the research regarding the size of the sample are recognized, and studies that investigate female university work in other contexts are encouraged, in order to obtain a more diverse and representative sample of these women.

The analysis also showed us the different forms of violence that students suffer at university. However, it was not possible, in this study, to cover the specificities and complexity of the impacts of all of them, so that it is also necessary to carry out future studies in the area in order to better investigate this intersectionality of forms of oppression , like the study by Oliveira, Nunes and Antloga.4

Finally, it is concluded that the impacts of the pandemic on the health of students need to be studied more carefully, taking into account the mobilizing and significant character of the topics related to the pandemic in their discourse. Although topics such as mourning, loneliness and lack of motivation have emerged in the focus groups, it is necessary to carry out more studies to better understand their implications and, thus, carry out effective institutional preventive actions.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Vieira A, Amaral GA. A arte de ser Beija-Flor na tripla jornada de trabalho da mulher. Saúde e Sociedade. 2013;22(2):403–414.

- 2. Graner KM, Cerqueira ATAR. Revisão Integrativa: sofrimento psíquico em estudantes universitários e fatores associados. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2019;24(4):1327–1346.

- 3. Zanello V. Saúde Mental, Gênero e dispositivos: cultura e processos de subjetivação. Curitiba: Appris; 2018.

- 4. Oliveira F, Nunes T, Antloga C. Dinâmica de prazer e sofrimento de estudantes negras de faculdades de Brasília- Epistemicídio, racismo e machismo. Psicologia Revista São Paulo. 2019;28(1):103–124.

- 5. Dejours C. Trabalho vivo volume 2: Trabalho e Emancipação. Brasília, Paralelo; 2012, p. 15.

- 6. Sousa LM, Sousa SMG. Jovens Universitários de Baixa-Renda e a Busca pela Inclusão Social via Universidade. Pesquisas e Práticas Psicossociais. 2006;1(2):1–13.

- 7. Facas EP. Protocolo de Avaliação dos Riscos Psicossociais no Trabalho-Contribuições da Psicodinâmica do Trabalho. Tese (Doutorado), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia Social e das Organizações, Universidade de Brasília; 2013.

- 8. Bispo ACKA, Helal DH. A dialética do Prazer e do Sofrimento de Acadêmicos: um Estudo com Mestrandos em Administração. Revista de Administração FACES Journal. 2013;12(4):120–136.

- 9. Bastos EM, Melo CSM, Machado PA, et al. Sofrimento e Estratégias Defensivas no Ambiente Acadêmico: um Estudo com Pós-Graduandos. Revista Interface. 2017;14(12):115–137.

- 10. Hirata H. Gênero, classe e raça: interseccionalidade e consubstancialidade das relações sociais. Tempo social.2014;26(1):61–73.

- 11. Malloy Diniz LF, Costa D de S, Loureiro F, et al. Saúde mental na pandemia de Covid-19: considerações práticas multidisciplinares sobre cognição, emoção e comportamento. Debates Em Psiquiatria. 2020;10(2):46–68.

- 12. Maia BR, Dias PC. (Ansiedade e depressão em estudantes universitários: o impacto da COVID-19. Estudos em Psicologia. 2020;37:2–8.

- 13. Facas EP, Mendes AM. Estrutura Fatorial do Protocolo de Avaliação dos Riscos Psicossociais no Trabalho. Núcleo Trabalho, Psicanálise e Crítica Social; 2018.

- 14. Veiga L, Gondim SMG. A utilização de métodos qualitativos na Ciência Política e no Marketing Político. Opinião Pública. 2001;7(1):1–15.

- 15. Backes DS, Colomè JS, Erdmann RH, et al. Grupo focal como técnica de coleta e análise de dados em pesquisas qualitativas. O Mundo da Saúde. 2011;35(4):438–442.

- 16. Bardin L. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1977.

- 17. Antloga CS, Monteiro R, Maia M, et al. Trabalho feminino: uma revisão sistemática da literatura em Psicodinâmica do Trabalho. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa. 2020;36(2):1–8.

- 18. Federici S. Calibã e a bruxa: mulheres, corpos e acumulação primitiva. São Paulo: Editora Elefante; 2017.

- 19. Vizzoto MM, Jesus SN, Martins AC. Saudades de Casa: Indicativos de Depressão, Ansiedade, Qualidade de Vida e Adaptação de Estudantes Universitários. Revista Psicologia e Saúde. 2017;9(1):59–73.

- 20. Mendes AM, Duarte FS. Mobilização subjetiva. In: Vieira FO, Mendes AM, Merlo ARC editors. Dicionário crítico de gestão e psicodinâmica do trabalho. Curitiba: Juruá; 2013: pp. 259–262.

- 21. Barbour R. Grupos focais. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2009.

- 22. DPO. Anuário Estatístico da Universidade de Brasília 2013-2017. DPO: Decanato de Planejamento, Orçamento e Avaliação Institucional. 2018.