Domestic violence is a phenomenon on which, for many years, there have been turbulent discussions in Poland – not only in the media and political forums, but also in the scientific community. The article presents analyses on the effectiveness of one of the key programmes addressed to perpetrators of domestic violence who are serving their sentences in prison. The Duluth programme, also known as the Duluth model, is essentially aimed at perpetrators of violence against female partners, however, it has seen many modifications and is widely used in the case of both custodial and non-custodial sentences. The results obtained indicate statistically significant differences in return to crime depending on whether the convicted person participated in the programme for perpetrators of violence or not. Among the convicts in the experimental group, i.e. those who had completed the program, the return-to-crime rate was 37%, whereas in the control group it was 55% – that is, it was significantly higher among those who had not completed the programme. As already mentioned, these differences were statistically significant.

Keywords: Domestic violence, Effectiveness of correctional and educational programmes, Abuse, return to prison, Perpetrator of violence, Duluth

According to official police statistics, about 27,000 proceedings are initiated annually in Poland under Article 207 Sections 1-3 KK [Polish Penal Code] (abuse of a family member), and just over a half of them (14,000 – 15,000) are ascertained crimes. According to court statistics, in 2018, 10,986 people were convicted by a final judgment under Article 207 KK. There were 8,358 sentences of deprivation of liberty and 1,702 sentences for restriction of liberty. On average, the proportion of penalties of absolute deprivation of liberty to deprivation of liberty with conditional suspension of execution is one to three (in 2018, 2,797 people were sentenced to absolute imprisonment, whereas the execution of penalty was suspended for 5,561 people). According to the statistics of the Central Administration of the Prison Service as of December 31, 2019, 3,448 final judgments under Article 207 KK were being executed.

However, the statistics presented do not fully illustrate the scale of domestic violence; they are only a thin slice of reality. It is estimated that 700,000 up to one million women experience violence in Poland every year.1 According to police statistics, 95% of perpetrators of domestic violence are men and 91% of victims are women and children.

Due to the scale of the phenomenon, measures to prevent and combat violence are clearly essential.2,3 Such measures involve creating appropriate programmes and procedures to support people who experience violence.3 Another extremely important element is to make the perpetrators themselves subject to appropriate influences. In addition to the typical therapeutic effects in Poland, the most frequently used solutions are correctional and educational programmes. The most well-known correctional and educational programme for perpetrators of violence is the Duluth model.5,6 It is widely used in the conditions of both custodial and non-custodial sentences.

This article presents the results of research on the effectiveness of the Duluth violence perpetrator programme.

The main objective of the research was to show the effectiveness of prison-based correctional and educational programmes for persons convicted of domestic violence.7 Two study groups (experimental group and control group) were included in the study.

The study involved 182 men born after 01.01.1960 with the final end of the sentence not earlier than 31.12.2014 and no later than 31.12.2015. On the basis of statistics of the Central Board of the Prison Service, at the beginning of January 2014, its employees prepared lists of all convicted men meeting the above criteria, currently in prisons, where programs for perpetrators of domestic violence were to be implemented. All trainers working in these establishments were given lists of convicts, from which they were to draw people for research. The procedure used was to ensure random selection of participants. Convicts were offered to participate in the study, with those assigned odd numbers (1,3,5) being offered participation in the experimental group and convicts assigned even numbers (2,4,6) being offered participation in the control group. All study participants were required to sign a consent to participate in scientific research, in addition, people from the experimental group who were to undergo a rehabilitation intervention were required to sign an application for participation in the program.

The study was carried out in fifteen prisons in Poland from February to June 2014, and the last participant of the study was released from prison in January 2015. Five years after the convicts had left prison, further analyses were carried out to verify how high the return-to-crime rate was among the subjects. The starting point of the project was the hypothesis that people who had participated in the Duluth correctional and educational programme for domestic violence perpetrators would be less likely to commit domestic violence-related crimes again after leaving the prison and, thus, less likely to be re-admitted to penitentiary facilities. To this end, analysis of data from the National Criminal Register on repeat offending and information from the Central Administration of the Prison Service on prison stays during the period in question were analysed.

In addition to the repeating of the offence, account was taken of the nature of the act for which the person was re-convicted and the time elapsed since their release from prison until their re-entry into prison.

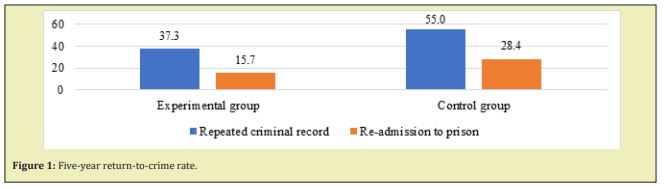

The empirical material collected allowed the development of a return-to-crime rate taking into account different time perspectives. As regards the five-year execution time, convicts participating in the correctional and educational programme for perpetrators of violence were less likely to repeat the offence and, as a result, less likely to be re-admitted to prison facilities (Figure 1).

These differences were statistically significant, which means that people who had completed the programme for perpetrators of violence in prison were less likely to re-commit the crime after leaving the facility than those who had not participated in such a program (chi 2(N=171, df=1) = 5, 570, p=0.018; Phi=0.180; p=0.018), and were less likely to be re-admitted to a prison facility (chi 2(N=183, df=1) =4,348, p=0,037; Phi=0.154, p=0.037).

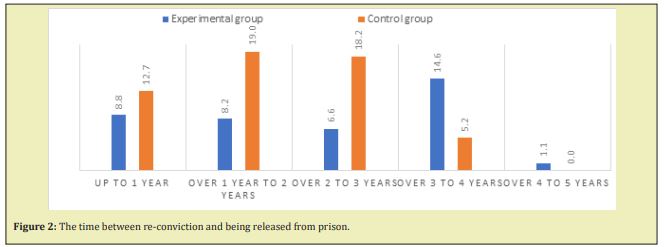

The subject of the analysis was also the time elapsed since the participants had left the prison facility until they were convicted again. It is worth noting that in the first period after leaving the penitentiary facility, there were considerably less convictions in the experimental group than in the control group. Over time, however, there were fewer convictions among the control group. This may have been related to the nature of the offence committed and the duration of the criminal proceedings and the associated procedures (see Figure 2 for details).

In order to better understand the reasons for re-offending and to investigate the factors that may somehow reduce or increase the effectiveness of the programme for perpetrators of violence, the data contained in the prison records have been analysed. Information was collected, among other things, on personal situation of the convicted person (e.g. family relationships, housing situation, professional situation, addictions) as well as their functioning in prison (e.g. rewards, penalties, relations with the staff and with co-inmates, taking up work, etc.).

The analysis of data concerning the types of offences for which the study participants were re-convicted does not indicate statistically significant differences between the type of act committed and the fact of completion of a correctional and educational programme (chi 2 (N=182, df=2) =5,124, p=0,077). In both the experimental and control groups, around 12% of participants were re-convicted of an offence against the family and care. The experimental group was dominated by convictions for abuse of a family member, while the most frequent offence in the control group was non-payment of maintenance.

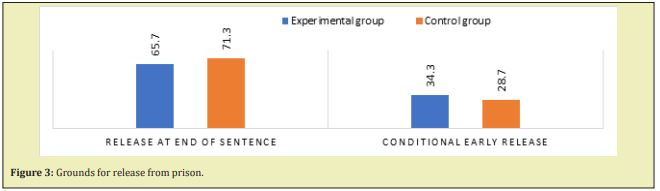

The majority of the participating convicts left the prison at the end of their sentence of absolute imprisonment. In the experimental group, one in three were granted conditional early release, while in the control group it was around 29% (see Figure 3). However, these differences were not statistically significant (chi2 (N=182, Df=82) = 2,143; p=0.342).

The functioning of the convicted person after leaving the prison is influenced not only by the impact to which they were subjected in the correctional process, but also by adequate preparation for re-entry into society. One element of such process would be, therefore, the possibility of granting a prison furlough. In Poland, a furlough may be requested, for example, for family visits, or it may be related to the performance of work outside of prison or participation in therapeutic or correctional and educational programmes.

In the study groups, on average, there were 3 furloughs granted per convicted person in the experimental group (SD=6.27) and 4 furloughs in the control group (SD=4.18).

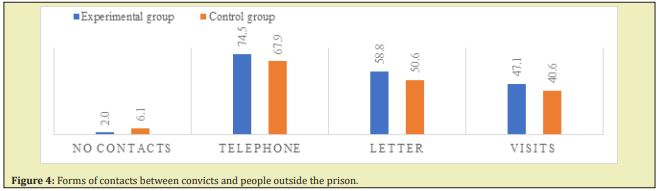

The most common form of contact between convicts and the "outside world" was telephone contact, with 75% of the experimental group and 68% of the control group using this possibility. Another popular form of correspondence were letters – with 59% and 51% of people, respectively. In the experimental group, nearly half (47%) of the contacts with persons from outside the prison were in the form of visits. In the control group it was slightly less –about 41%. An interesting result is indicated by the percentage of people who were not in contact with anyone from outside the prison. In the experimental group, such individuals accounted for less than 2%, while in the control group it was 6%. This result was compared with the return-to-crime rates in the groups studied, as it was assumed that having support networks, family and non-family contacts would promote the proper social functioning and, above all, would be a positive indicator for receiving social support after leaving the prison. However, no statistically significant differences were observed (Figure 4).

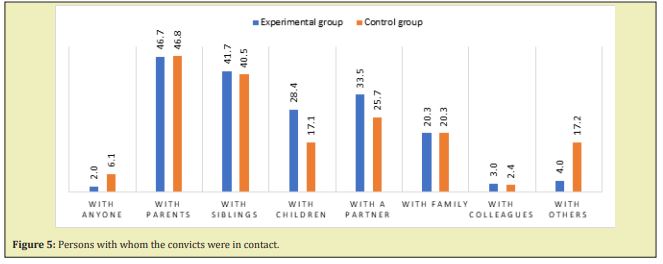

Another important element examined in the context of re-offenders, other than the type of contact, is the kind of persons with whom the convicts maintained some kind of a relationship. The most common ones were parents (47%) and siblings (41% and 42% respectively). For both the experimental and control groups, these rates were similar. The situation was also similar with regard to distant relatives - such contacts were maintained by one in five convicts. The largest differences in contacts between the groups compared were observed in relation to maintained relationships with children (28% and 17% for experimental and control groups, respectively) and female partners (contact with wife, unmarried partner living together, girlfriend) 34% and 26%, respectively (see Figure 5). This result is not surprising, as the majority of those surveyed in prison were in custody because of the crime consisting in the abuse of a partner and children.

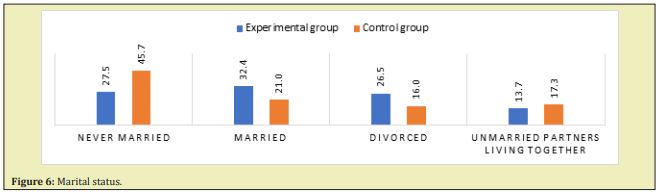

In the groups analysed, the distribution of responses regarding the relationship status indicates that people in the experimental group were more likely to be in formalised relationships (one in three of the experimental group and one in five of the control group). Nearly twice as many people were divorced (27% in the experimental group and 16% in the control group). As already mentioned, the vast majority of cases concerned the abuse of a partner, but not only; the victims were also parents and siblings. It is worth pointing out here that some of the convicts lived in a common household with the victims, including those who were in legal separation or divorced (Figure 6).

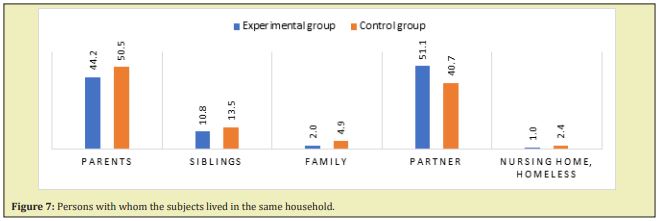

In the two groups compared, the most subjects lived with their parents (see Figure 5) and partners; this is also consistent with the distribution of responses regarding the marital status and the victims of abuse (Figure 7).

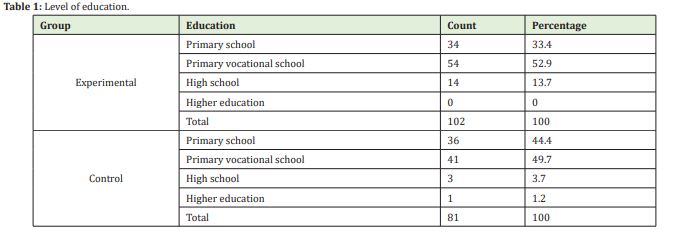

The distribution of the level of education of the convicts participating in the study indicates that the experimental group was better prepared in terms of professional qualifications, as about 65% of those surveyed had post-primary education (basic vocational education – 53%, average – 14%). In the control group, the proportion of people with primary education was higher and amounted to 44%. Nearly half had basic vocational education, while the total of around 5% had secondary or tertiary education (see Table 1).

During their stay in prison, the convicts were given the opportunity to supplement their education and attend specialized courses and trainings to increase their chances for employment after leaving the penitentiary institution. Only two convicts benefited from the opportunity to complete their education (one person from the experimental group graduated from the primary vocational school and one person from the control group finished primary school). 13% of those surveyed in the experimental group and 10% of those in the control group benefited from vocational courses. The most common training courses offered were: brick paving, hydraulics, carpentry, computer science, green space conservation, building renovation, exterior plastering and welding.

Factors related to the convicted person's socialisation process are an important element both in assessing the risk factors for the occurrence of criminal behaviour and in assessing the effectiveness of the impacts used. In the literature on the subject, particular attention is paid to the relationship between the functioning of the family and the influence of the closest contacts.8 It highlights, among other things, the significance of parental addiction, occurrence of various personality disorders and mental illnesses in the family, as well as parental crime.9

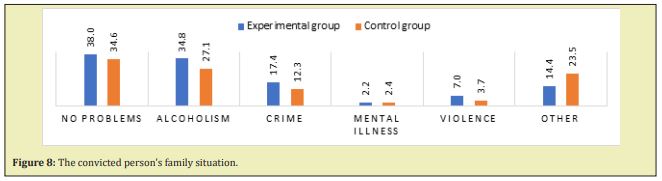

In the populations compared, the experimental group differed slightly in terms of the absence of problems in the primary family. One third of the subjects reported no problems with the family. One in three of the experimental-group subjects and one in four of the control-group patients grew up in a family with an alcohol problem (one parent's addiction). One in six, on the other hand, grew up in a family with a criminal history. In a small percentage of cases (about 2%), the families were affected by mental illness (see Figure 6). The convicts from the experimental group were slightly more likely (7%) to grow up in families where violence occurred than those in the control group (4%) (Figure 8).

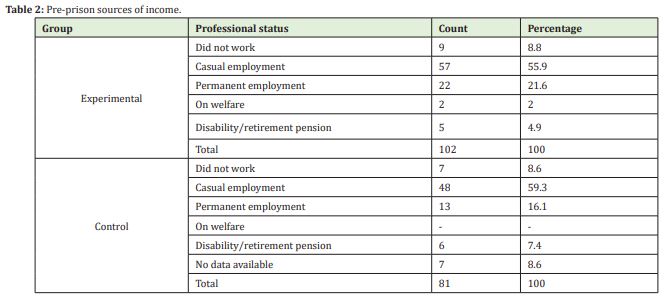

The majority of respondents had a permanent or casual source of income, while about 9% were out of work. See Table 2 for a detailed distribution of responses.

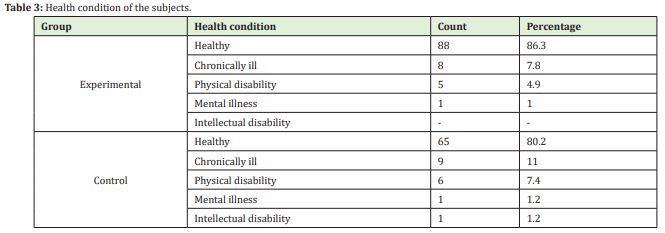

The health condition of the subjects was also analysed. In the majority of cases, there was no information about any problems in this regard. In the two groups compared, the situation was similar, with 86% and 80% of the experimental group and control group, respectively, being healthy. About 8% of those surveyed in the experimental group were chronically ill, 5% were physically disabled and in one case the subject was diagnosed with a mental illness. In the control group, one in nine were chronically ill, just over 7% of people were physically disabled; an intellectual disability was found in one case, and a mental illness in another one (see Table 3).

An important aspect in estimating the effectiveness of the programme, especially among perpetrators of domestic violence, is dependence on alcohol or other psychoactive substances. As highlighted in the literature on the subject, in many cases alcohol plays a triggering role in aggressive and violent behaviour by releasing the brakes on the control over one’s emotions and behaviour.10

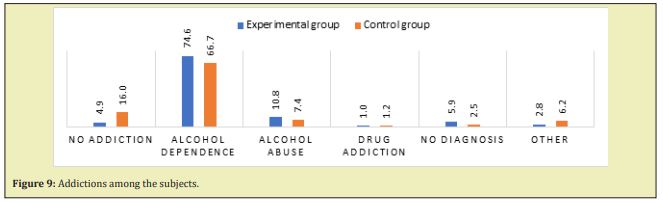

It is worth noting that both in the experimental and control groups the majority of subjects had an addiction problem. In the experimental group, only 5% of subjects were not found to be addicted to any substance and in 6% of cases the subject had not been examined in this regard. Three quarters were diagnosed with alcohol dependence, while one in ten was diagnosed with alcohol abuse; 1% of those convicted in the experimental group were drug addicts, and 3% were cross-addicted. In the control group, no addiction was found in 16% of the convicts participating in the study, and about 6% of them did not have an adequate diagnosis. The vast majority were found to have one form of addiction. In about 67% of cases it was an addiction to alcohol, slightly over 1% – to drugs, and slightly over 6% suffered from a cross-addiction (alcohol and drugs, and in one case – alcohol and medication) (Figure 9).

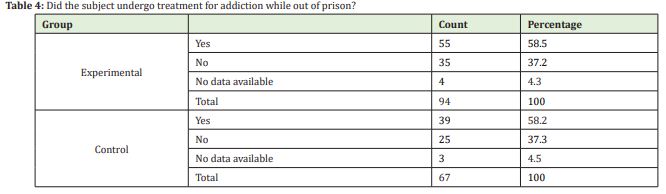

In both the experimental group and control group, the proportions of addicts who attempted to undergo treatment were similar (58%). However, one in three of those who had a problem with addiction did not seek treatment (see Table 4).

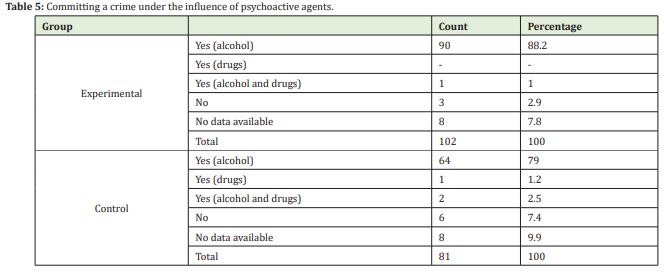

As mentioned above, alcohol plays a significant role in abuse-related offences.11 According to empirical data, the vast majority of acts were committed by perpetrators under the influence of alcohol; in the experimental group it was 89% of the offences and in the control group it was 83% (Table 5).

One indicator of the subsequent effectiveness of correctional and educational impacts may be the offender’s attitude towards the crime committed. This appears to be important in the population studied, as in the experimental group, a critical attitude towards the offence was found among a third of the subjects, whereas in the control group it was one quarter.

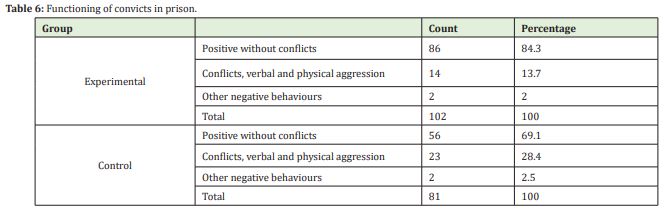

Analysis of data on the functioning of convicts in prison indicates that people from the experimental group functioned much better in prison facilities, with only 16% reporting conflicts with co-inmates or with the staff. In the control group, the percentage was 31%, i.e. almost a third (Table 6).

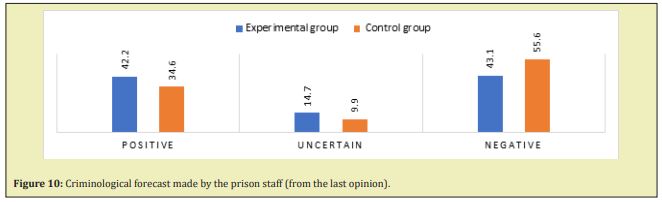

According to the most recent criminological forecasts available in the prison files prepared by the prison staff, about 42% of the convicts in the experimental group had a positive forecast, while in the control group it was the case for one in three convicts. In 15% and 10% of the experimental and control groups, respectively, the forecast was uncertain, as both negative and positive indicators were found. Interestingly, a negative forecast was made with regard to 43% of those convicted in the experimental group and more than half (56%) of the control group. It should be stressed that the actual return-to-prison rate was 16% and 28% for the groups analysed. The compliance of the forecast with the actual return rates was within 40% (Figure 10).

Among the factors that were indicators of a positive prognosis in the criminological opinions, the following were mentioned most frequently:

- Positive behaviour in prison, no disciplinary penalties.

- Participation in a correctional and educational programme for perpetrators of violence.

- Participation in other correctional and therapeutic programmes.

- Having family support, keeping in touch with the family.

- Positively assessed progress in criminal rehabilitation.

- Work while in prison.

- Criticism of the crime committed.

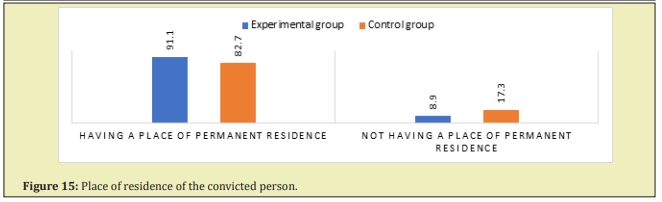

- Having a place of permanent residence.

Among the g factors giving a negative outlook, the most common were:

- Aggressive behaviour while in prison, conflicts with co-inmates and with the prison staff.

- No criticism of the crime committed.

- Lack of motivation to participate in correctional and therapeutic interactions.

- Multiple criminal records.

- Alcohol dependence, lack of treatment.

- Conflict with the family with whom the convict was to live with after leaving the prison.

As previously mentioned, the prison files contained also uncertain criminological opinions, which meant that the same convicted person had a number of factors giving a positive and negative prognosis. Here are some examples:

- Negative indicator: No plans to take up employment outside of prison, little dedication to the rehabilitation process. Positive indicator: the death of the sister who was abused by the convict;

- Negative indicator: Return to crime. Positive indicator: critical attitude to crime, participation in rehabilitation programmes and good behaviour in prison;

- Negative indicator: The rehabilitation process is going well, but has not been completed yet. Despite completing the Duluth programme, the convict is not fully aware of the harmfulness of the crime committed.

- Negative indicator: The convicted person does not guarantee that they will not commit a crime again.

- Positive indicator: There is progress in the rehabilitation process, the convict participated in a therapy related to the treatment of alcohol addiction, completed the Duluth programme, you can see changes in his thinking, has a job, functions well in prison.

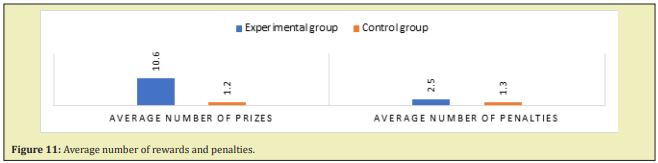

One of the factors showing how a convicted person functions in prison is the number of penalties and rewards. In the two groups compared, the average number of rewards per convict in the experimental group was 11, with an average of one reward per convict in the control group.

The results relating to the number of penalties applied to convicts are more alike. On average, there were 2-3 disciplinary penalties per convict in the experimental group; in the control group, the average was one penalty (Figure 11).

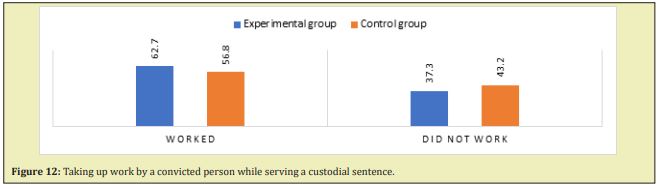

As highlighted in the literature, one of the effective rehabilitation impacts can be work.12 Not only does it ensure a constructive use of time during the time in prison, but it allows for the convicts to accumulate the necessary funds for ongoing expenses or to be used after leaving the facility. For organisational reasons, not all convicts in Poland have the opportunity to take up work while in prison. It should also be stressed that not all detainees are interested in this possibility. In both groups studied, the majority of convicts worked during their time in prison (63% and 57% for the experimental and control groups, respectively) (detailed distribution of responses is shown in Figure 12).

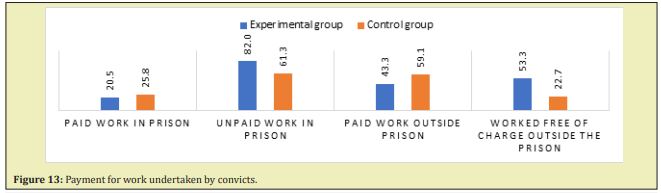

A significant proportion of the convicts had the opportunity to take up work in prison, some of them – outside prison. In the experimental group, 86% of the subjects worked in the facility and 14% worked outside prison. In the control group, the proportion of inmates working in the prison facility was 78% and outside – 22%.

As previously mentioned, convicts who were working while in prison could be paid for their work. However, the work offered to inmates was not always against payment. It can be seen that work performed in prisons was usually unpaid, while work outside the prison was more likely to be paid. The detailed distribution of responses is shown in Figure 13.

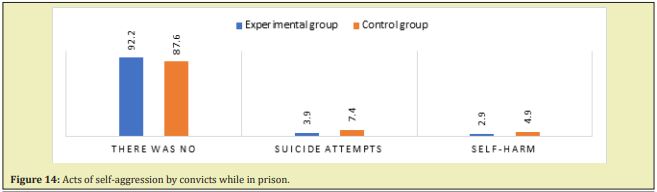

The factors that measure a convict’s functioning and ability to cope with emotions and stress include acts of self-aggression, which can occur during the stay in prison. In the populations compared, in most cases such situations did not take place (see Figure 14).

In total, self-committed aggressive acts (suicide attempts and self-harm) occurred in the case of approximately 7% of the convicts participating in the study and 12% of the control group (Figure 14).

Another factor that is mentioned among the positive or negative indicators for the convicts is the fact of having a place of permanent residence. In the compared populations, the convicts, in the vast majority of cases, had a place of residence where they could return to after leaving the prison facility. In the experimental group it was 91% and in the control group it was 83% of the convicted.

It should be pointed out, however, that the place of residence of the respondents was, at the same time, the place of residence of the victim. As a result, it could have been a negative indicator, not so much a supportive factor (Figure 15).

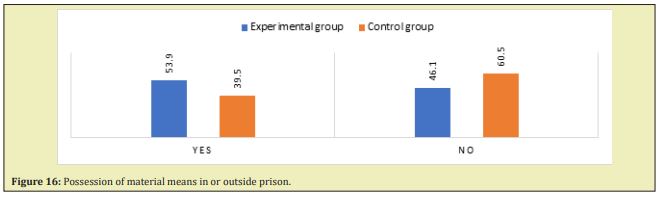

The majority of convicts from the experimental group (54%) had some financial resources that they accumulated during their time in prison (paid for work, money sent by relatives or friends). In the control group, the percentage was significantly lower and amounted to 46% (Figure 16).

In the case of one in ten convicts from the experimental group, it was found that possession of financial means was related to the criminal environment outside prison, while the same was true for one in four convicts in the control group.

It should be stressed that one in four respondents (regardless of the group) returned to the environment marked by negative factors such as addiction or crime.13-18

As shown above, violence is a pervasive phenomenon. We observe it in the media and in the broadly-understood culture, thus, it touches many aspects of human life. It is, therefore, particularly important to take action on the basis of different disciplines in order to prevent and combat various forms of violence.

The article presents analyses on the effectiveness of one of the key programmes addressed to perpetrators of domestic violence who are serving their sentences in prison. The Duluth programme, also known as the Duluth model, is essentially aimed at perpetrators of violence against female partners, however, it has seen many modifications and is widely used in the case of both custodial and non-custodial sentences.

The results obtained indicate statistically significant differences in return-to-crime rates depending on whether the convicted person participated in the programme for perpetrators of violence or not. Among the convicts in the experimental group, i.e. those who had completed the program, the return-to-crime rate was 37%, whereas in the control group it was 55% – that is, it was significantly higher among those who had not completed the programme. As already mentioned, these differences were statistically significant.

It is worth noting that in the first period after leaving the penitentiary facility, there were considerably less convictions in the experimental group than in the control group. Over time, however, there were fewer convictions among the control group. It would be necessary to consider whether this could be a lasting effect of correctional and educational impacts. The influence was becoming less and less clear over time. In fact, it is proposed in the literature on the subject-matter that persons who have completed a correctional and educational programme should participate in a follow-up module from time to time, which would allow for consolidation of the acquired knowledge.

Of course, the analysis should not disregard other psychosocial factors affecting both the course of the correctional process and the motivation of convicts to participate in the impacts. All the factors located outside the prison and related to the family environment in which the violence took place are also significant.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that although the Polish experience seems to be quite optimistic, as it indicates the effectiveness of the programmes carried out, which then translates into lower return-to-crime rates, it undoubtedly requires further research and verification.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Gruszczyńska B. Przemoc wobec kobiet w Polsce: aspekty prawnokryminologiczne. Wolters Kluwer Polska. 2007.

- 2. Saltzman LE, Green YT, Marks JS, et al. Violence against women as a public health issue: Comments from the CDC. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):325–329.

- 3. Chrisler JC, Ferguson S. Violence against women as a public health issue. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1087(1):235–249.

- 4. Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, et al. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(5):465–476.

- 5. Bates E, Graham Kevan N. Intimate partner violence perpetrator programmes. In: Wormith JS, Craig LA and Hogue TE Editors. The Wiley Handbook of What Works in Violence Risk Management: Theory. Research, and Practice. Wiley. 2020; pp. 437–450.

- 6. Rodgers ST. Womanism and Domestic Violence. In: Encyclopedia of Social Work. 2020.

- 7. Postępowania wszczęte i przestępstwa stwierdzone z art. 207 KK za lat. 1999–2020.

- 8. Rode D. Psychologiczne uwarunkowania przemocy w rodzinie: charakterystyka sprawców. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. 2010.

- 9. Barczykowska A. Zastosowanie modelu RNR w diagnozie resocjalizacyjnej dorosłych sprawców przestępstw–rozwiązania angielskie. 2015.

- 10. Serafin P, Jakubczyk A, Podgórska A, et al. Przemoc pomiędzy partnerami i zachowania ryzykowne u osób uzależnionych od alkoholu i innych substancji psychoaktywnych. Alkoholizm i Narkomania. 2012;25(3):289–305.

- 11. Różyńska J, Socjalnego NP. Przemoc wobec kobiet w rodzinie. 2013.

- 12. Konopczyński M. Metody twórczej resocjalizacji: teoria i praktyka wychowawcza. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. 2006.

- 13. Czarnecka-Dzialuk B, Drapała K, Ostaszewski P, et al. W poszukiwaniu skutecznych reakcji na przestępczość. Programy korekcyjno-edukacyjne. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar. 2017.

- 14. Helios J, Jedlecka W. Współczesne oblicza przemocy. Zagadnienia wybrane. 2007.

- 15. Przemoc w rodzinie - dane do 2011 roku.

- 16. Statystyka roczna.

- 17. Przemoc domowa i przemoc wobec kobiet. Co statystyki mówią o sytuacji w Polsce?

- 18. Wójcik D, Drapała K, Więcek Durańska A. Ewaluacja programu Trening Zastępowania Agresji ART oraz programu korekcyjno-edukacyjnego Duluth. 2015.