With the killing of George Floyd in 2020 and the subsequent focus on black existence, itis perhaps timely to revisit a previous historical period – the 1970s which saw theemergence of the civil rights movement and the transformation of black consciousness and identity.Both psychosocial and existential theories highlight the relationship between context and the development of identity. Drawing on the work of Erikson, Cross describes

stages of identity development from negro to black which he originally related to the historical context of the black consciousness period of the 1970s but later, developed into a tool to measure black identity. This model depicts identity as developing in fixed stages with objective and measurable characteristics. The black existential approach focuses on the construction of identity within a context shaped by an individual’s experiences. Black existential philosophy aims to explore how different black experiences shape different manifestations of black identity construction. This articlereviews these two perspectives. I conclude that the black existential perspective

produces richer knowledge about the existence of black people. Using the example ofhow second generation British born black Jamaicans constructed their identity during the 1970s, it is possible to see how this construction was shaped by their lived experiences in Britain at this time.

Keywords: Black identity, Black existential philosophy, Psychosocial perspective on black identity, Black existential perspective on black identity, Black jamaican diaspora

It was not only the Covid-19 pandemic that shook the world in 2020. The killing of George Floyd in America not only provoked an outpouring of global outrage, but it alsoreignited the debate about the value of black existence and the impact of antiblack racism on black identity. The young black people who are living through this current historical period will be impacted by this experience and it will influence their sense of self as they make sense of this and other experiences that they encounter as they live their lives as black people.

Fifty years ago, the 1970s saw another historical period in which black people in America, Africa, the Caribbean, and Europe responded to their experience of antiblack racism and were galvanised collectively, for the first time since the end of slavery, to restore value to their black existence and construct a new ‘black’ identity.

This paper explores how psychosocial and black existential theories account for how a black identity or identities develop. With reference to the period of the 1970s, there will be an analysis of the experience of one group of black people – the children of the Windrush Generation born, in the UK to parents of Jamaican heritage, and how they responded to the twin phenomenon of antiblack racism in Britain and the emergence of black consciousness and black pride movements during the 1960s and 1970s. The experience of this group of black people situated in 1970s Britain, illustrates the multitude of different black identities that emerge even when individuals have a shared group experience. It further illustrates how the development of a black identity can only be understood by an exploration of the lived existence of black people in differentcontexts.

Early psychosocial research on black identity focused on the impact on black people of racial segregation in America in the early to mid-part of the twentieth century.1,2 Clark and Clark were concerned with how educational segregation impacted the self-esteem of black children and led to selfhatred. The rationale behind their ‘Doll’ experiments1 was to assess the level of racial identification. The experiments focused on whether racism was internalised by assessing how a child interacted with a given doll. For example, a black child favouring a white doll would indicate self-hatred. The work of Kardiner and Ovesey exposed the effect of racial segregation and discrimination on the personality ofblack Americans in general, leading them to conclude, that it left a lifelong psychological scar on black people. While these experiments were designed to show the impact ofsocial policies on psychological function, they failed to capture what it felt like to be segregated and deemed inferior. Furthermore, self-hatred among black people was construed as a universal and enduring phenomenon. Erikson3 described the identity crisis besetting black people during the 1960s; the estrangement of black people from the world and themselves and their struggle to reject an imposed negative ‘negro’ identity. The black American psychologist Cross3 argued that the rejection of a ‘negro’ identity took place for black people globally with the emergence of the black consciousness and black power movements chiefly inAmerica, Africa, and the Caribbean during the 1970s. Cross, inspired by Erikson’s eightstage model of identity development (1980[1959]), described this identity transition in his own five-stage model of black identity.The rationale for a model of black identity (entitled ‘Nigrescence’) which Cross first developed in 1971, was to contextualise the concept of self-hatred as a stage in the development towards a black identity and not as an enduring response to antiblack racism as described in the work of Clark and Clark1 and Kardiner and Ovesey(1951). According to Cross, the 1970s, heralded a change from a negro identity; from one of self-hatred to one of self-pride. In an update to his model in the 1990s, Cross revised his theory and now emphasised that Nigrescence was not just an historical account of a ‘negro to black’ identity transformation in the 1970s – it was and is aprocess of stage identity development that all black people experience. He argues:

‘whether we talk about the new Negro in the 1920s, the Negro-to-Black metamorphosis in the 1970s, or the search for Afrocentricity in the 1990s, the five stages of Black identitydevelopment remain the same: Pre-encounter (stage 1) depicts the identity to be changed; Encounter (stage 2) isolates the point at which the person feels compelled to change; Immersion-Emersion (stage 3) describes the vortex of identity change; and 5Internalisation-Commitment (stages 4 and 5) describe the habituation and internalisation of the new identity’.4

According to Cross this updated model now known as the Cross Racial Identity Scale, not only describes the development of a black identity it can be used as a means of assessing racial attitudes among black people; to measure the extent to which an individual possesses a healthy attitude to their blackness.4 Cross’s original work was a significant shift away from previous research that too often characterised black psychological functioning as one of self-hatred. The strength of the model lies in the way it captures the historical moment in the 1970s, when the rise of black consciousness enabled black people to reconstruct the previous negative notion of blackness into something of value. To this end, it fits with a psychosocial perspective that connects identity development with context. However, its weakness is its attempt to measure black identity. There appears to be an assumption that such an identity can be assessed objectively so that it can be said of a person they are ‘black enough’. As an attitudinal study, what is missing are the stories and experiences which lie behind the different attitudes that individuals express. There is, I believe, a need to understand what life experiences have led individuals to see themselves and others in the way they do and what it means to them to position themselves in a particular way towards their blackness and towards a black social group.

Black social identity

Theories on black social identity, that focus on blackness as a social group, draw upon classic Social Identity Theory (SIT) closely associated with the work of Tajfel and Turner.5 However, the literature on black social identity reveals that the notion of a black social group identity is not a straightforward one.Drawing specifically on the American experience in the 1970s, Shelby6 argues that there are two ways of conceiving black social identity which derive from two theoretical perspectives. In the common oppression theory, black people are united because of antiblack racism and the focus is on working together to improve the lives of all black people. The collective determination theory proposes a type of black nationalism in which black people as a group, see themselves with a distinct racial, cultural history and objective black identity. The focus in this latter theory is not so much on combatting racism more on an autonomous black social group focused on political, economic, and cultural self-determination - distinct from other racial groups.6 These two conceptualisations of a black social identity are historically rooted in the works of Washington (1986[1901]7-9 and inspired the black consciousness and black pride period that emerged during the 1960s and 1970s. Shelby suggests that black people have typically identified with either one of these group identities.6 However, there is a question as to whether this dualistic conceptualisation reflects the actual experience and behaviour of black people. For example, there is no account of what it means to the individuals in a context to hold a specific position towards their blackness; how their identity and identification connects with their experience of their life experiences and the extent to which such identities and identifications are weak or strong, singular or multiple or a complex blend constructed and reconstructed over time. In contrast to psychosocial theories of development, the existential phenomenological perspective focuses on seeking to understand how, because of an individual’s existence in context (and the meaning they attach to their lived experiences), they construct theirindividual sense of self. A branch of existential philosophy – black existentialphilosophy, focuses on the lived existence of black people in context.

Black existential philosophy is influenced by postcolonial theory and the ideas of black philosophers such as7-14 However, the focus is on how existential ideas relate to the specific existence of black people of African descent. Black existential philosophy draws particularly on the ideas of Sartre15,16 and frames these within the experience of black people who, because of slavery and antiblack racism, have been cast as inferior human beings.13 The philosophy (based on the cultural particularity of people of African descent) critiques phenomenological existential philosophical ideas purporting to be universal yet, it is argued, are in fact limited to the cultural particularity of the European subject (Henry,2005). Furthermore,13 appears to draw a distinction between ‘existentialism’ which he regards as: ‘a fundamentally European historical phenomenon’13 and ‘existential philosophy’ which encompasses concerns such as: ‘freedom, anguish, responsibility, embodied agency, sociality and liberation’.13 What makes this a black existential philosophy is that theseconcerns are applied to the situated lived experience of black people:

‘Implicit in the existential demand for recognising the situation or lived-context [is the specific existence]of Africana people’s being-in-the-world’13

This emphasis on specific existence is a key existential principle. Existential philosophy focuses on how each of us as individuals negotiate the existential challenges of freedom, responsibility, choice, agency, and meaning as we encounter everyday experiences - in a context and always in relationship with others. These are universal principles. However central to black existential thought is that because of the systematic negation of blackness, individual black existence is always framed by the need to restore value to blackness, and this underpins black subjectivity and identity.

Early black existential thinkers such as Du Bois7 were concerned with the interaction between the social conditions of black people in segregated America and the impact of this form of apartheid upon their consciousness. Du Bois describes the notion of double consciousness in the black experience as black people seeing themselves through the eyes of the European (white America) who looks back at them in disdain. Du Bois uses the term ‘second sight’ to describe how black people see themselves from the position of white people and what they see is a ‘negro’, an inferior subject.7 This experience of inferiority leaves the black subject facing a unique existential struggle to create their individual identity.10 A blackidentity is therefore crucial as a way of giving value to the black subject; freeing themselves from racial stereotypes so that they can experience and be experienced as black individuals. However, the critical question again is, what is a black identity?

Perspectives on black existential identity

There are two broad perspectives that have emerged within the tradition of existentialthinking on black identity.17,18 One perspective appears to position9black identity as something to be acquired or recovered from a pre-slavery blackexistence rooted in Africa. The work of,19 illustrates this firstperspective. Cesaire was a Martinican poet, closely associated with developing theconcept of Negritude (a term from the French that means the process of becoming black in a white world).19 saw this process as a way in which people of Africandescent could reject colonial identity and acquire their own Pan African identity. Cesaire’s position fits with the idea of a black African identity with pre-existing essenceonly to be interrupted by slavery.8 Not only was there a pre-slavery blackidentity it is conceived as singular in nature. This characterization of black identity runscounter to one of the fundamental principles of existential philosophy namely, that eachof us construct our identity as we experience living our lives in relation to others in acontext. To this end,13 who is considered one of the architects of blackexistential philosophy has a different perspective. Gordon focuses on how identityemerges from the existence of being a black individual in a particular context.13 In his seminal work Existence in Black: An Anthology of Black ExistentialPhilosophy(1997), Gordon asserts that in accordance with existential philosophy thereis not one perspective on black existence. Gordon’s work showcases ideas andperspectives from black writers (some avowed existential thinkers and others not) fromdifferent cultural and historical backgrounds and different disciplines to reveal thebreadth and depth of black experience, and how these different experiences help toshape the construction of a black identity. Writing in the anthology,12 illustrates how Jamaican ideas (from Garvey to Rastafarianism) not only influenced theglobal black consciousness and black pride movements in the 1970s, but enabledJamaicans and the Jamaican diaspora to construct a black identity with specific Jamaican10 historical and cultural references. Furthermore, for the Jamaican diaspora, for examplein the UK, their black identity was also shaped by their particular experiences of livingin Britain during this period.

The emergence of black identity in Jamaica and the diaspora during the1970s

Writing specifically from an English-speaking Caribbean experience, Henry12 draws upon the work of Du Bois7 and argues that black people need to stop seeing themselves and other black people from a white European perspective. Henry observes that what Du Bois refers to as ‘second sight’ (double consciousness) implies that there is a ‘first sight’. This first sight enables the black subject to reclaim their own self-consciousness, to see themselves through their own eyes. Henry notes that one way in which Jamaicans historically have challenged the false consciousness of ‘second sight’ is through the theology of Rastafarianism. Rastafarianism emerged from the Jamaican poorer classes in the early part of the twentieth century. The ideology drew upon key ideas of Garvey8,9 Garvey encouraged the black diaspora in the early part of the twentieth century, to reject the European notion of Africa and blackness as inferior. Instead, he encouraged black people to acknowledge the historical achievements of Africans and to see that black people could once again achieve greatness.9 However, Garvey did not appear to see this as a return to a past Africa, instead it was a way of reframing black history to give black people pride in their past and hope for their future.20 To this end, the theology is:

“oriented towards a courage that 11reconstitutes the self in spite of such social phenomena as class/race domination and stereotypical redefinition”.21

This new black self is constituted with reference to the symbolic positioning of Ethiopia (the only African country not to be colonised) as the spiritual home for the ‘free’ black Rastafarian.21 Within Rastafarianism there is an interpretation of biblicaltext that challenges dominant European translation. Rastafarianism evokes biblical metaphors such as the use of the term ‘Babylon’ to describe a physical and mental place of captivity. While the ideology offered hope and a call to black pride, it manifested a more spiritual dimension than Garveyism which focused more on black self-determination akin to a type of black nationalism.9,20 Following Jamaica’s independence from Britain in 1962, Jamaicans embarked on a search for a new identity. Henry argues that the significance of Rastafarianism (which resurged in Jamaica post-independence) to Jamaica, the wider Caribbean and the Jamaican diaspora is that it provides a theology that challenges the legacy imperial social system that undermines both individual and collective black identity.21 In some respects, the rise of the civil rights and black power movements in the United States and Rastafarianism in Jamaica during the 1960s and 1970’s was an attempt to rediscover a lost African history. In Jamaica, during this period, Hall (a Jamaican born sociologist who came to Britain as part of the Windrush Generation)notes:

‘The culture of Rastafarianism and the music of reggae – the metaphors, the figures or signifiers of a new construction of Jamaican-ness [emerged]’.22

Asmentioned earlier, such metaphors included references to black people being in 12captivity in ‘Babylon’ yet reminding themselves of their value and their need to focus on freeing their minds ‘from mental slavery’.23 Hall sees the period of the early 1970s in particular as historic; the first time, Jamaicans in Jamaica and overseas ‘discovered themselves to be black’ (Hall,1994:231). However, in doing so, they constructed a cultural identity of ‘Jamaicanness’ grounded in an Africa of the past but also reconfigured in the Jamaica of the present. In other words, the lyricsof roots reggae music described the contemporary daily lives of ordinary Jamaicans their struggle, oppression and the fight for freedom and referenced this to the historical struggles of all black people. These are clear existential themes. For many of the children of the Windrush Generation born in Britain, whether they were of Jamaican or other Caribbean heritage, they could look to Jamaica and Jamaican culture to help them construct a new black identity. While not all young black people at this time became Rastafarians, the roots reggae music which described black existential struggle and ayearning for peace and freedom as well as extolling the value of blackness and the need for black pride, seemed to resonate with their experience of alienation, isolation, and asearch for meaning and identity in the UK. Many of these British born black people felt they now had value and pride in their blackness as they constructed their black identitycharacterised by Jamaican culture and Rastafarian ideology.24 writes specifically on the experiences of the children of the Windrush Generation during the 1970s and 1980s who together with their parents, formed the first significant black British population. Gilroy describes the experience of the mainly Jamaican Windrush immigrants who arrived as British subjects (from 1948 to mid1960s) to the UK only to face antiblack racism. Their children, born in the UK would 13experience similar rejection. In Gilroy’s thesis we see an evocation of Du Bois’s7 double consciousness dilemma facing black Americans (was it possible to be both black and American), repositioned within the British context. Gilroy poses the question whether it is possible to be both black and British. For many young black people born to Windrush parents, the answer was no. It was the specific experience of rejection that led many to conclude that they could not be both black and British and that is why, for many, a black identity became the identity that they cleaved to. However, it is the specific nature of this black identity that many young black people constructed that Gilroy finds problematic, namely a ‘discovered’ singular ‘authentic’ black identity. A type of black nationalism24 For Gilroy, the reality of the diasporic experience is that it is inextricably linked to European and African history. Therefore, the idea of a return to a distinct objective preslavery identity is as false as any white nationalist identity (Gilroy, 1993). Gilroy makes an important point and one which challenge, for example, Garvey’s perspective on black social identity - revealing how black nationalism is in bad faith. However, the reality of the experience of black people in Britain particularly during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s led many to fashion their black identity in a fixed objective way. For many it was a way of surviving their daily lives in the country of their birth, a country that rejected them. It is only by understanding the context of their existence at this time, that it is possible to understand how and why some black people adopted this position towards their blackness and what it meant to them to do this.

The lived experience of some British born black women of Jamaican heritage

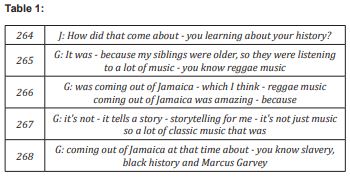

In 2018, I undertook a qualitative study from an existential phenomenological perspective into the lived experience of six professional black British born women, born to Jamaican parents of the Windrush Generation (Sewell,2020).The aim of the research was to make known how the lived experience of these Windrush daughters shaped their relationship with their self and others as illustrated by their relationship to work and achievement. This was a qualitative study from an existential phenomenological perspective, using the critical narrative analysis method (CNA). Two semi-structured interviews were undertaken to capture the participants’ narratives. The participants’ narratives were analysed using critical theories, in particular, black existential philosophy. Analysis of the findings showed that early experience of racism led to self-hatred. However, the 1970s black consciousness periodled many to adopt a new black identity,In the findings, two of the participants described their experiences of ‘becoming black’ during the 1970s. Georgina described that for her, becoming black, also meant becoming Jamaican. She regarded the two as inextricably linked. Furthermore, she saw her blackness as authentic, and she judged the authenticity of other black people against her black identity. In the transcript below, she describes how she came to construct herblack identity:Table 1

In the case of Melanie (who was of mixed Indo/black Jamaican heritage), she describes how she eschewed her Indian heritage in the 1970s, and described herself from then onas an African woman. Melanie describes how reggae music and Rastafarianism became important to her, and that this was the time that she,

‘relinquished any Asian or Indianidentity that I had which was my father’s side and focused more on my African identity, diaspora identity as it were, and would have described and still describe myself as an African, black African woman’ (ll784-787).

Gilroy’s argument is that these examples of an essentialist type of black identity are akin to the white nationalism it purports to challenge. Further, the creolization of Caribbean heritage (as exemplified by Melanie’s heritage) and the interconnectedness ofEuropean, African, and Caribbean history, meant that such a purist ‘African’ black identity rooted in a ‘unified’ past black African identity is a myth.24 However, what I feel is most important here are the symbolisms and the meaning that such an identity held for these women. They could now see themselves as black women with value and pride.

What is also interesting is the way in which both these women constructed a black identity in response to their experiences in the 1970s. Georgina saw her identity linked closely to her Jamaican heritage while Melanie, although describing her pride in her Jamaican culture and the influence of Rastafarianism in particular on her construction, chose to identify herself as a black ‘African’ woman. This illustrates how Melanie’s experience of being black (with Jamaican Indian/African heritage) in Britain, which was sometimes one in which she felt different from other black people, contributed toshaping her particular stance towards her black identity.For many of the participants in my study their experience of antiblack racism in their formative years led to a struggle with self-hatred. The period of the 1970s particularly the social events in Jamaica, offered them and their parents a way to construct a black identity that gave them pride in their blackness and Jamaicaness. In the context of the experiences of rejection and hostility against the Windrush Generation and their children, this identity construction was a way to survive psychologically and to create a ‘sense of self’ that acted as a buffer against the relentless negativity towards their blackness. Of course, not all the participants constructed the same black identity. Forsome, self-hatred remained a feature throughout their lives, while others constructed very fixed or more fluid identities. It is only when hearing their stories that it was possible to understand how their experience of their experiences shaped their identityconstruction.25-27

The work of Cross was a shift away from psychosocial theories that saw the impact of antiblack racism on black people as a lifelong psychological trauma of self-hatred. In his 1970’s original Nigrescence model, we see an acknowledgment of the impact of the historical context of the 1970s with the eschewing of an old ‘negro’ identity and thedevelopment of a new ‘black’ identity. However, the development of the model in the 1990s into a measurement tool of black racial attitudes, presupposes an objective universal black identity exists and that this can be measured and scored. Thisundermines the importance of context. The black existential perspective as articulated in the ideas of Gordon, focus on the different situated experiences of black existence. The example of how some of the children of the Windrush Generation constructed theirblack identity in response to their experience and characterised by their Jamaican heritage, illustrates the complexity around the development of black identity and how it is inextricably linked to experiences within a context.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Clark KB, Clark MP. Racial Identification and Preference in Negro Children. In: Newcomb TM, Hartley EL, editors. Readings in Social Psychology. New York: Holt. Rinehart & Winston; 1947. p.169‒178.

- 2. Kardiner A, Ovesey L. The Mark of Oppression: Exploration in the Personality of the American Negro. Cleveland: World Pub. Co; 1962.

- 3. Cross WE. The Negro to Black Conversion Experience. Black World. 1971;20(9):13‒27.

- 4. Erikson E. The concept of identity in race relations: Notes and queries. Daedalus. 1966;95(1):145–171.

- 5. Cross WE. Shades of Black: Diversity in African American Identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1991.

- 6. Tajfel H, Turner JC. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. 2nd Ed, 1986. p. 7‒24.

- 7. Shelby T. Foundations of Black Solidarity: Collective Identity or Common Oppression? Ethics. University of Chicago Press; 2002.

- 8. Du Bois WEB. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Dover Publications;1994.

- 9. Garvey A. Garvey and Garveyism. New York: First Collier Books; 1970.

- 10. Garvey M. Selected Writings and Speeches of Marcus Garvey. New York: Dover Publications; 2004.

- 11. Fanon F. Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto Classics; 1986.

- 12. EllisonR. Invisible Man. UK: Penguin Classics; 1952.

- 13. Henry P. Rastafarianism and the Reality of Dread. In: Gordon, L Existence in Black: An Anthology of Black Existential Philosophy. New York: Routledge. 1997.

- 14. Gordon L. Black Existential Philosophy. In: Gordon L, editor. Existence in Black: An Anthology of Black Existential Philosophy. New York: Routledge; 1997.

- 15. Gordon L. Bad Faith and Antiblack Racism. New York: Humanity Books; 1999.

- 16. Sartre JP. Being and Nothingness. Oxford: Routledge Classics. 1943.

- 17. Merleau Ponty M. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge; 1945.

- 18. Hall S. Negotiating Caribbean Identities. New Left Review. 1995;209: p. 3–14.

- 19. Hall S. The Question of Cultural Identity. In: S Hall, D Held, D Hubert, K Thompson, editors. Modernity Anlntroduction to Modern Societies. Blackwell; 1996. 690 p.

- 20. Cesaire A. The black student. 1935.

- 21. Sewell T. Garvey's Children: The Legacy of Marcus Garvey. London: Voice. Communications Ltd; 1987.

- 22. Henry P. Rastafarianism and the Reality of Dread. In: Gordon L, et al. Existence in Black: An Anthology of Black Existential Philosophy. New York: Routledge; 1997.

- 23. Hall S. Cultural Identity and Diaspora. In: Williams P, Chrisman L, editors. Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory: A Reader. London: Harvester; 1994. p. 227‒237.

- 24. Marley B. Redemption Song [CD‒ROM]. Uprising. Available: The Island Def Jam Music Group; 1980.

- 25. Gilroy P. The Black Atlantic‒Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso Books; 1993.

- 26. EriksonE. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York and London: WW Norton & Company; 1980.

- 27. Sewell JM. What does work, achievement and identity mean to black British women? The lived experience of professional black British women of Jamaican heritage. DCPsych thesis, Middlesex University/New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling; 2020.