The current primary mental health care system in Ireland is limited. A different vision of primary mental health care requires national awareness of the limitations of ‘A Vision for Change’1 and it’s followed up policy document, ‘Sharing the Vision’.2 Awareness alone is insufficient, requiring the additional properties of ambition, conviction, and engagement to overhaul the current system. In this third paper on Primary Mental Health Care, a truly changed vision of care is presented and demonstrated to be successfully at work in one third level counseling service, at the University of Limerick. This model is contrasted with the current medicalized model and proposed as a replacement model of primary mental health care for Ireland. A number of recommendations are made, including the suggestions that the proposed model of service delivery based on the model at the University of Limerick be piloted outside of the third level sector, within the Health Service Executive of Ireland.

Keywords

Counseling, Health service, Care

The Department of Health (DOH) Statement of Strategy opens with a statement pertaining to the reforming of key public services (like health) in order that everyone can enjoy physical and mental health and wellbeing.3 A similar message is supplied within the most recently published mental health policy document for Ireland ‘Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone’2 which is a follow up document to Ireland’s ‘A Vision for Change’ (AVFC)1. However, it is not in-fact currently the case that ‘everyone’ can enjoy such services, as proposed by the DoH documents. There are strict eligibility criteria for the Irish Primary Mental Health Care (PMHC) service, known as ‘Counseling in Primary Care’ (CIPC) service. Access demands service users to be over the age of 18, to hold a General Medical Services (GMS) card, and to be referred through their GP or through members of the Primary Care Team (PCT) with the knowledge of their GP.1 These criteria appear to remain unchanged within ‘Sharing the Vision’ (StV).2 Nonetheless, both the 2016 and the 2020 documents clearly endorse the further development of primary care services as well as greater integration and person-centred service delivery. Capturing the essence of primary care, the 2016 DoH statement also endorses a model of care that is ‘delivered at the lowest level of complexity consistent with patient safety’ (p. 5). The recent StV document promises improved pathways to support from the Voluntary Community Sector and better integrated and coordinated services within mental health care.2

The 2015 review of AVFC policy suggested that more mental health professionals should be available in the CIPC primary care setting.5 Whilst the 2020 StV document references talk therapy, peer support, social prescribing, and digital health programmes at primary care or community level support, it does not reference the funding of further posts to increase access to talk therapies at primary care.2 Whilst the authors accept and agree with the need for more mental health professionals within primary care, they do not do so in support of the limited CIPC model. The authors also endorse and acknowledge the need for further integration and collaboration of care for patients, but do so with the view that the specialty of mental health care resides with those specifically trained within the discipline (i.e., psychologists, psychotherapists, and counselors) rather than with GPs who are placed at the helm of the mental health referral process, by to both AVFC1 and StV.2 Furthermore, unlike the shared care models of CIPC1 and ‘Access to Psychological Therapies Ireland’ (APSI)6 models (discussed in papers 1 & 2),7,8 the authors advocate that the PMHC services be located independent of medically based services and triaged appropriately in order to make best use of resources.

Two previous papers7,8 in this series on Primary Mental Health Care (PMHC) have set the stage for this final paper. Within paper 1, the authors suggest that the current PMHC system in Ireland is insufficient, limited, and restrictive. Paper 2 examined PMHC in three separate countries; Scotland, England, and the Netherlands, identifying their strengths and limitations. In this third paper on PMHC, the aim is to demonstrate a different vision of PMHC for Ireland based on an existing, working model at one community setting at a large Irish university. This paper also aims to demonstrate the applicability and suitability of such an approach for PMHC in Ireland as a replacement to the current system. To complete this paper, it is proposed that this community example be replicated on a pilot basis within a Health Service Executive (HSE) community setting.

Our presentation for a different model of PMHC is placed within the university setting. Given the recent recognition within StV2 of the vulnerability of young people up to the age of 25, the location of our example service is ideal. For context, a brief background to youth and college students’ mental health is provided in advance of introducing the ideal PMHC community service.

The vulnerability of young people was highlighted almost a generation ago in America.9 This group is at significant risk for the development of mental health problems such as anxiety, mood problems, impulse control problems, and substance use problems. Half of lifetime problems commence by age 14 and three quarters by the age of 24. It stands to reason, therefore, that interventions aimed at prevention and early intervention need to focus on young people.9 Three large scale studies have explored youth mental health in Ireland; two exploring the mental health of young people, the ‘My World Survey’10 and one identifying how the mental health needs of students can be addressed, the ‘Reach Out Ireland Survey’.11 The first ‘My World Survey’ (MWS1)10 collected information on over 8000 young people from all 26 counties and represented all universities across Ireland. The second ‘My World Survey’ (MWS2)12 found an increase in the reported incidence of both depression and anxiety when compared to the results from MWS1. The surveys also found problematic drug and alcohol use, and lifestyle factors such as sleep and social media use as having an impact on student mental health. Similar to Kessler et al.,9 findings revealed mental health difficulties to emerge in early adolescence and peak around the age of 20. The ‘Reach Out’ survey was also a large-scale study of over 5000 students which identified the mental health status of college students as well as their help-seeking behaviors and preferences in order to better address their needs.10 Reach Out findings identified nearly half (44%) of the student population to report mental health difficulties. The comparatively lower mental health status of university students against their peers in the general population has been well documented, both at home in Ireland12 and abroad.14-17

Waiting lists for access to PMHC services can be long, both in the UK18 and in Ireland.1 National health services are therefore both unlikely and ill-equipped to provide timely support to students with mental health problems. The University campus, as a circumscribed community, is an ideal context for PMHC delivery. Such services tend to be embedded within the university campus, accessible to the student population, and integrated with other university support systems. Given these factors, university based counselors are familiar with the specific issues facing students, such as difficulties associated with their age, the activities and studies with which they are engaged, and the constraints, deadlines, and requirements they face with respect to their educational status.18 Research demonstrates that student counseling is effective in supporting students throughout their degree,20 contributing to improved university experience21 as well as retention at university.22 Counseling also has been found to reduce levels of student distress whilst at university.21-24 Students have also revealed that they would prefer to engage with counseling within the university rather than outside of it,11 undoubtedly alleviating both the financial burden and the responsibility of care within the national health services.

Recent Irish data from the ‘Psychological Counselors in Higher Education Ireland’25 reveals almost 14,000 students attended student counseling nationwide25 from a community of 220,000 students over one single academic year, 2018/2019. The number represents 6.3% of students nationwide. Compare this with the data from ‘Jigsaw’ (the national center for youth mental health) which has worked with nearly 37,000 young people over the 12-year period, 2008-2020, since it opened up.25 The comparison of statistics reveals student counseling services to be the largest national provider of professional mental health support for young people aged 18-25. The embedded nature of student counseling, familiarity with student concerns, and psychological approach to mental health treatment as standard, student counseling services provide great savings to the health budget by

- a. Removing the cost of expensive psychotropic medication as a first line of treatment

- b. Relieving pressure on statutory mental health by negating inappropriate referrals and making appropriate ones more efficiently

- c. Reducing caseloads of GPs at primary care and waiting lists at secondary mental health care services.27

Demand for talk therapies is on the increase.9,28 It is not unique, therefore, that student counseling services have observed an exponential increase in demand and attendance over the past number of years both in the UK29-31 and in Ireland.11 As many as half of new entrants to university in Ireland are now reporting a lifetime history of mental health concerns11,31 and many of these are seeking support whilst at university.

With over 16,000 students enrolled at the University of Limerick (UL), the need and demand for support at the counseling service is high. Attendance at the UL student counseling service (known as UL Éist[1]) has increased steadily over the years, with 908 students presenting in 2014/15, 978 in 2015/2016, 1136 in 2016/2017, 1139 in 2017/2018 and 1074 in 2018/2019.32 Core presenting difficulties include anxiety, low mood, academic concerns, and relationship problems. The stark increase in service demand carries with it implications for third level counseling services.33 There is no doubt that a suitable service model is required to meet this increasing demand within a service of limited resources.

In response to meeting increased demand with limited resources, UL Éist first rolled out a self-referred, stepped-care service in 2011, modeled on White.34 Embedded within the campus and community of UL, the counseling service aims to deliver early, non-stigmatized intervention, and efficient services to the student population, maximizing its existing resources whilst providing effective interventions at the required level of need. The geographic location of UL Éist is important. Located within the main building of the campus, but along a quiet corridor, it is both easily accessible to the student body as well as relatively private. Furthermore, UL Éist is directly opposite the medical service. This separate, yet close, location of the counseling and medical services provides students with the distinct choice between psychological or medical care for mental health concerns. It is clear from attendance figures at UL Éist that students have no difficulty in identifying the counseling facility as appropriate to meet their mental health needs. Furthermore, there is no evidence that students are attending UL Éist inappropriately. In summary, given the choice, students are very capable of self-selecting the service that is most suited to their psychological needs.

UL Éist is an easily accessible community-based service. Through the use of a stepped care model and self-referrals, the service is available to all students registered with the University. By embedding the service within the community, it serves, this allows students to access the service independently when the need arises, rather than first having to navigate the Irish healthcare system before receiving a service.

The knowledge and skill-base among degree and masters level psychology graduates has been long recognized by UL Éist. Whilst APs have only recently been formally employed within the establishment of a national child and adolescent PMHC service of the HSE, APs have been pivotal to and embedded within the stepped-care service structure at UL since its inception. Reflecting the national shift, the role of the AP within the UL Éist has also recently evolved from voluntary status to paid employment. This shift not only recognizes the valuable existing skills inherent among such graduates and provides invaluable employment, but it also stabilizes and secures service delivery over the academic year with fixed term contracts.

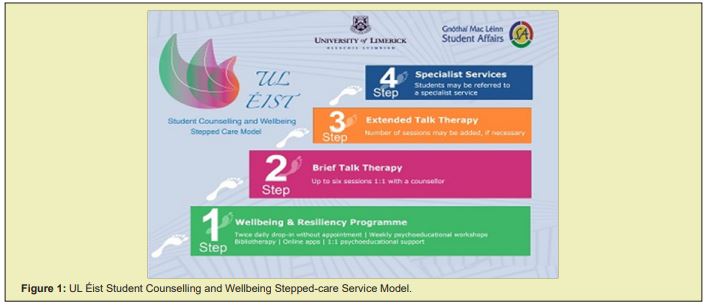

The team at UL Éist is currently comprised of one administrator, two senior psychologists, four senior psychotherapists, eight trainee psychotherapists, and three assistant psychologists. In total, there are 18 members of the team, equivalent to 11.5 whole time posts. The administrator is responsible for making initial appointments. The two senior psychologists co-manage the service, supervise trainees and assistants, conduct assessments, provide consultations, and supply interventions, therapy, or external referrals for presentations of greater complexity. The psychotherapists provide psychological support and therapy for students presenting with moderate to complex needs, whilst the trainee and pre-accredited psychotherapists provide therapeutic input for students presenting with lower-level risk and complexity. Assistant psychologists conduct all screening, risk assessment, follow-up, and low-intensity cognitive behavioral based interventions and psychoeducation to the community. This work is subsumed within the stepped-care framework which is depicted in Figure 1. The stepped-care model at UL Éist has evolved over the past six years as resources and demand have shifted. The assessment session and steps of the model as they currently work is expanded upon below.

The assessment element of the stepped-care model may be considered either as part of step 1 or as a pre-entry phase of the stepped-care model. At UL Éist, assessment is conducted as part of the ‘Drop-In’ service, which for the sake of convenience, is advertised as part of step 1. Twice a day, drop-in of one hours’ duration each, are provided throughout the academic semesters. These can be attended by any UL student without prior appointment. APs, trained and supervised by senior psychologists, conduct a brief assessment with each student. Risk, priority, symptoms, and students’ needs are determined via intake interview and psychometric screening utilizing the 34 item ‘Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation’ (CORE-34).34 Questions relating to risk of dropping out and impact of problems on academic studies are also asked. This process takes between fifteen to twenty minutes. With three APs running this step, up to 20 students can be seen daily at drop-in. The APs then debrief with the senior psychologists and a support plan is designed based upon the presenting issues and student needs. The senior psychologists sign off on all cases and can be called upon, if necessary, to intervene on the spot with any potentially risky presentations.

Step 1: Low-level supports

Interventions at step 1 are designed to maintain general wellbeing, specific goal achievement, and early intervention. Many supports at this level are available to the student community at UL without requiring attendance at UL Éist. These include bibliotherapy; advice about online apps and web support; and weekly psychoeducation via email on topics such as stress management, low mood, managing anxiety, coping with exams, and progressive muscular relaxation. An additional, yet slightly more intensive step 1 support provides a student who has attended drop-in to be referred for up to four sessions of 1:1 cognitive behavioral psychoeducational support with an AP. This support is tailored and goal orientated to help the student develop skills and understanding relevant to their presenting difficulties. Alternative, or additional, step 1 supports vary for students. Examples include but are not limited to: student follow-up; liaison with tutors and lecturers; engagement or referral to chaplaincy/medical service/students’ union/academic supports, etc.

Step 2: Short-term talk therapy (1-6 sessions)

Following drop-in and debrief, a student may be progressed immediately to step 2 of the service. Alternatively, the student might have engaged with step 1 and find that they require more in-depth support or assessment. At this point, they are then ‘stepped-up’ to step 2. The student will either be progressed to a psychologist for a more detailed assessment or they can avail of 1:1 therapy with a trainee psychotherapist, qualified psychotherapist, or psychologist for a maximum of 6 sessions. Not all students require or need as many as 6 sessions, however. In-service annual reports indicate that students attend on average only 4 sessions of counselling. Some students require a one-off session of 60-90 minutes duration to talk through their issues at greater depth but do not require on-going work. Where appropriate, students are also encouraged to utilize group workshops, bibliotherapy, or online apps to aid them. As with step 1, additional supports within the university might be recommended or promoted.

Step 3: Longer-term talk therapy (6+ sessions)

All students who attend for 6 sessions are reviewed. For a minority of students, longer-term therapy is required without the need for referral to an external or specialist service. These students are ‘stepped-up’ to step 3 for on-going therapy. Following completion of this step, most are either ready to complete therapy and leave the service or be ‘stepped-down’ to step 1 for well-being maintenance.

Step 4: Referral to specialized or external supports

At any point in their engagement with UL Éist, a student may be referred to specialist or external services including, but not limited to: external community mental health care services at secondary care level; crisis liaison teams within the local hospital; rape-crisis or crisis pregnancy services; drug or alcohol addiction supports; financial supports, bereavement supports, etc. Where students have capacity, referrals are discussed with them and made with their consent. Students at risk will have been assessed at drop-in and have supplied both consent to risk-management and consent to contact a named relative as an emergency contact. Such students may be immediately ‘stepped up’ to step 4 from drop-in or move between the various steps prior to such referral. Decisions are based upon initial presentation as well as information that emerges throughout service use.

Flexibility is the core strength of the stepped-care model. As is clear from the description above and from the general understanding of stepped-care as put forward by White (2008),35 the model is self-correcting, meaning students can move between the steps or leave and re-enter the stepped model at any point in time. Furthermore, steps can be combined; a student might be referred for step 1 and step 2, while others attending may require step 4 referral at some time during their treatment.

As with many such services, waiting lists can occur. At UL Éist, waiting times have extended to 4 weeks at peak periods throughout the academic year in the past. This has reduced to two weeks over the academic year 2018/19 with the introduction of 1:1 cognitive behavioral support. Such waiting times compare favorably to those at CIPC (75% are met within 6 weeks and 95% are met within 18 weeks).4 The triaging system implemented via screening and risk-assessment at drop-in means that those requiring immediate support can be prioritized or quickly referred to specialist services. Those who are at less risk can be provided with a range of supports at step 1 of the model, including returning to drop-in as necessary.

Modelling itself on the ‘Healthy Ireland’ Initiative (the national framework for action to improve the health and wellbeing of people living in Ireland),36 UL adopted a Healthy Campus Initiative over the academic year 2017/2018. Mental health has emerged as high on the priority for the UL community. To support both staff and students, funding and developments are taking place university wide that will undoubtedly enhance and compliment the resources offered by UL Éist to students. Not only has UL provided funding to UL Éist for the employment of three full-time APs, but the investment in a Health Promotion Officer has resulted in a full-time position being created as of 2019. The provision of online mental health support is one specific action item for mental health under this recent initiative, as well as reflecting recommendation 2 made within StV.2 A proposal for the purchase and introduction of an evidence based, online suite of cognitive-behavioral modules, known as ‘Silver cloud’ is underway as of June 2020, with an implementation date of September 2020 identified. It is hoped that this addition will serve to enhance step 1 of the stepped-care model employed at UL Éist and provide an acceptable engagement with mental health care to those 25% of students who have hitherto ‘coped alone’.10

The current model of PMHC in Ireland is built upon a medicalized model of care, requiring GP referral for psychological therapies, an over-reliance of psychopharmacology,27,37 and almost exclusive reference to diagnosis and treatment (as is evident throughout the AVFC and StV documents) rather than on helping people understand and manage their distress. As stated, shortcomings of this model also include the requirements to be aged over 18 and to have a medical card. Waiting lists are long,4 meaning that difficulties are likely to have become more entrenched and chronic38 before receiving support, thus undermining the essential element of primary care and leaving little room for prevention.

White35,39 proposed that PMHC stepped care models are not only staffed by mental health practitioners but also managed by specialists in mental health, such as clinical or counseling psychologists. The authors agree that such specialists in mental health are ideally trained for spearheading change and the future development of PMHC in Ireland and have demonstrated that such a system runs smoothly and efficiently when staffed in this way, without any need for GP gate-keeping or referral.

It is proposed by the authors that, like UL Éist, the Irish PMHC system becomes separated from the medical model in terms of staffing, ethos, and location in order to form and endorse a non-pathological approach to mental wellbeing. This would truly demonstrate implementation of the ‘Positive Mental Health and Wellbeing’ approach suggested with StV2 rather than simply paying the idea lip-service.

It is envisaged that the proposed implementation of the UL Éist stepped care approach would, if absorbed as the national model of care, result in a reduction in waiting times to access PMHC in Ireland. Following on from a reduction in waiting times, this may also impact the severity of mental health episodes that members of the public are presenting with, as well as a potential reduction in relapses.40 Access to PMHC would not be restricted by financial status, age, or type of presentation. Transforming PMHC in Ireland would have a positive effect for generations, allowing mental health care in Ireland to have the focus and resources which were originally outlined in 2006 in AVFC.

The framework of service delivery presented at the counselling service within UL is considered the nearest to best practice based upon the literature and the associated arguments made within our series of three articles. The authors recognize the anecdotal nature of the presented service model and potential bias inherent within our endorsement. As such, we have generated some recommendations based upon the contents of the papers. These range from immediate to long-term in nature.

Immediate

The authors have exemplified the stepped-care model in use at UL. However, despite data suitable for internal annual reports, the service and the model lack an empirically sound basis as yet and would benefit from formal evaluation of a number of elements. Firstly, a formal evaluation of service provision at every step of the model would lend empirical validity to the stepped care model. Resources need to be sought and sourced to realize such an evaluation. Findings could then be formally disseminated rather than anecdotally argued as in the present paper. Secondly, in order to assess the relative success or preference of a service separated from the medical model (in practice and logistics), a service user satisfaction survey would be necessary which could then be compared with those that exist within the current Irish model.38

Short-term

UL Éist is effectively utilized by the community it serves. It provides a clear and unequivocal choice to students who are seeking mental health care. Whilst anecdotal observation and feedback are promising from the perspective of the service, they lack the punch of hard data when contributing to the literature. Research suggests that self-referral is on the increase.41 Therefore, a formal comparative evaluation is required to empirically identify the number of students presenting with psychological and emotional concerns to the medical service at UL and compare this with the numbers presenting to UL Éist. Such research could also identify the delivery of mental health care offered and provided at the medical service compared to that provided by UL Éist service. An additional, more formal piece of research could also empirically identify the percentage of people presenting to GPs outside of the UL community for emotional and psychological concerns and then compare this with the percentage of students presenting to the UL medical service for similar concerns. This would reveal hard data pertaining to whether or not the provision of choice reduces mental health presentations at GP services.

Long-term

The effective piloting of models of care is an efficient route to national change, as evidenced by the APSI pilot.6 Once having internally piloted the UL Éist stepped-care model, it is proposed that the local HSE region roll out a similar framework based upon the UL model. The two pilots could be compared and contrasted for effectiveness, service user satisfaction, and length of waiting lists. Comparisons might also be made against the APSI and CIPC models to identify whether or not location and GP referral impact service use and treatment. From there, a national implementation of the model could then be placed on the agenda, replacing medically led care, replacing CIPC, and most importantly of all, challenging the principles of ‘A Vision for Change’.

This paper, the third of a series of three on PMHC, clearly articulates and demonstrates a model of PMHC in a community setting that combines the best elements of effective care. Of note, UL Éist benefits from; self-referral, easy access, short waiting lists (compared with CIPC), and effective assessment and management by psychologists and mental health staff, as suggested by Richards and Whyte.42 There is no need for reliance or deferral to GPs for assessment or referral thus permitting choice for the student as well as streamlining of professional expertise within the respective medical and mental health services.

AVFC1 stated ‘Each citizen should have access to local, specialized and comprehensive mental health service provision that is of the highest standard’, but this has yet to be achieved after 14 years since publication. The authors propose that the model and service evidenced at UL exemplifies change that truly is ‘visionary’ in nature. Rather than endorsing ‘A Vision for Change’ our vision instead calls for ‘A Change of Vision’.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Irish Department of Health & Children. A vision for change: report of the expert group on mental health policy. Dublin: Stationary Office, 2006.

- 2. Irish Department of Health. Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone. Dublin: Stationary Office. 2020.

- 3. Department of Health. Statement of strategy. 2016-2019. 2016.

- 4. Mental Health Reform. A vision for change: nine years on: A coalition analysis of progress. Dublin: Mental Health Reform; 2015.

- 5. Health Service Executive. Counselling in Primary Care Services: National Evaluation Study. Report of Phase 1. 2018.

- 6. McHugh P, Brennan J, Galligan N, et al. Evaluation of a primary care adult mental health service: Year 2. Mental health in family medicine. 2013;10(1):53‒59.

- 7. Aherne D, Smith L, Shea OJ. Primary Mental Health Care Part 1: A Critical Review of the Irish System. Submitted to Clinical Psychology Today. 2020.

- 8. Aherne D, Smith L, Shea OJ. Primary Mental Health Care Part 2: Three European Primary Mental Health Care Examples as Basis for Change to the Irish System. Submitted to Clinical Psychology Today. 2020.

- 9. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593‒602.

- 10. Dooley BA, Fitzgerald A. My world survey: National study of youth mental health in Ireland. Headstrong and UCD School of Psychology; 2012.

- 11. Karwig G, Chambers D, Murphy F. Reaching out in college: help-seeking at third level in Ireland. Reach Out Ireland. 2015.

- 12. Dooley BA, Connor OC, Fitzgerald A, et al. My world survey 2: National study of youth mental health in Ireland. Headstrong and UCD School of Psychology; 2019.

- 13. Houghton F, Keane N, Murphy N, et al. Tertiary level students and the Mental Health Index (MHI-5) in Ireland. Irish J Appl Soc Stud. 2011;10(1):7.

- 14. Roberts R, Golding J, Towell T, et al. The effects of economic circumstances on British students' mental and physical health. Journal of American College Health. 19991;48(3):103‒109.

- 15. Stewart Brown S, Evans J, Patterson J, et al. The health of students in institutes of higher education: an important and neglected public health problem?. Journal of Public Health. 2000 Dec 1;22(4):492‒499.

- 16. Webb E, Ashton CH, Kelly P, et al. Alcohol and drug use in UK university students. The lancet. 19965;348(9032):922‒925.

- 17. Stallman HM. Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychologist. 2010;45(4):249‒257.

- 18. Wallace P. The value of an in-house counselling service in FE and HE. Association for University and College Counselling Journal. 2011. p. 30‒33.

- 19. Mental Health Reform. Pre Budget submission 2019. 2018.

- 20. Rickinson B. The relationship between undergraduate student counselling and successful degree completion. Studies in Higher Education. 1998;23(1):95‒102.

- 21. Wallace P. The impact of counselling on academic outcomes: the students’ perspective. Association for University & and College Counselling. 2012. p. 6‒11.

- 22. Wallace P. The impact of in-house counselling on academic outcomes. Association for University and College Counselling Journal. 2012. p. 28‒31.

- 23. Connell J, Barkham M, Mellor-Clark J. The effectiveness of UK student counselling services: an analysis using the CORE System. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2008;36(1):1‒8.

- 24. McKenzie K, Murray KR, Murray AL, et al. The effectiveness of university counselling for students with academic issues. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2015;15(4):284-288.

- 25. PCHEI. PCHEI Stats summary for May 200 Conference. Unpublished data collected on behalf of Psychological Counselling in Higher Education in Ireland. PCHEI. 2019.

- 26. Jigsaw. Online data available online. 2020.

- 27. Oireachtas. Second interim report: recommended actions arising from progress made to date. Joint committee on the future of mental health care. 2018.

- 28. Clark D, Turpin G. Improving opportunities. The Psychologist. 2008;21(8):700.

- 29. Bewick BM, Gill J, Mulhearn B, et al. Using electronic surveying to assess psychological distress within the UK student population: a multi-site pilot investigation. E-Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008.

- 30. Storrie K, Ahern K, Tuckett A. A systematic review: students with mental health problems-a growing problem. International journal of nursing practice. 2010;16(1):1‒6.

- 31. McLafferty M, Lapsley CR, Ennis E, et al. Mental health, behavioural problems and treatment seeking among students commencing university in Northern Ireland. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0188785.

- 32. UL Éist. Annual Report. Unpublished; 2019.

- 33. Broglia E, Millings A, Barkham M. Challenges to addressing student mental health in embedded counselling services: a survey of UK higher and further education institutions. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2018;46(4):441‒455.

- 34. Mellor-Clark J. Special Issue: Developing CORE System benchmarks. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2006;6(1):1‒87.

- 35. White J. Stepping up primary care. Psychologist. 2008;21(10):844‒847.

- 36. Department of Health. Healthy Ireland-a framework for improved health and wellbeing 2013-2025. 2013.

- 37. Health Service Executive. Health Service Executive Primary Care and Mental Health Group. Advancing the shared care approach between primary care and specialist mental health services: a guidance paper. Naas: Office of the Assistant National Director Mental Health; 2012.

- 38. Bebbington PE, Meltzer H, Brugha TS, et al. Unequal access and unmet need: neurotic disorders and the use of primary care services. Psychol Med. 2000;30(6):1359‒1367.

- 39. White J. Clinical psychology in primary care. Primary care psychiatry. 2000;6(4):127‒136.

- 40. Reichert A, Jacobs R. The impact of waiting time on patient outcomes: Evidence from early intervention in psychosis services in England. Health Economics. 2018;27(11):1772‒1787.

- 41. Collins P, Walsh Z, Walsh A, et al. A 360 degree evaluation of stepped-care psychotherapy: APSI yrs 4-5. Mental Health Review Journal. 2020;25(2):1‒2.

- 42. Richards DA, Whyte M. Reach Out: National programme student materials to support the training and for Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners delivering low intensity interventions. UK: Rethink Mental Illness, 2011.