Some adults with Asperger syndrome are at increased risk of suicidal ideation/behaviour and require a high level social support. Psychological and physical abuse in early childhood might increase suicidal risk at later age. Intact executive functioning might facilitate suicidal behaviour..

Keywords

Suicidal behaviour, Asperger syndrome, Hopelessness, No exit, Executive function

Suicide and self-harm are worldwide major health issues, with suicide being worldwide the tenth leading death cause.1 It is not entirely clear what the key indicators are for recognising individuals at increased risk, and there is a need for developing clear population based interventions, practices, procedures and policies.1 Raja suggests the neglect of research in suicidal behaviour in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome (AS) and autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) is due to the relatively low numbers of suicidal behaviour. Adults are often treated by psychiatrists who are not very familiar with childhood-onset disorders and therefore might misdiagnose suicidal behaviour in ASD and AS and relate it to schizophrenia, without recognising the link with suicidal behaviour and autism.2

AS is usually identified as a subgroup of ASD, and the absence of language delays or intellectual disability.3 Cassidy et al.3 report that diagnoses in AS are normally delayed until the age of 11 years, whereas it is at 5 years with autism, and that transition to adulthood often brings a lack of support systems. According to Brüne et al.4 the highest predictor for suicide seems to be social isolation, hopelessness and negative self-appraisal. Balfe &Tantam5 found that up to 95% of adolescents and adults with AS were harassed at school and 40% reported suicidal ideation. Hannon et al.6 claim, even though studies have a high number of males, it is likely that the issue involves females on similar levels. Mukaddes & Fateh7 report that all of their female adolescents displayed suicidal behaviour, even though there were 13.5% females. Abadie et al.8 found that an adolescent with AS (Age: 15) was bullied and socially excluded and then formed suicidal thoughts, and that suicidal behaviour was significantly higher in ASD and AS than in any other patients. The adolescent searched the internet for methods for killing himself and to make his body disappear, so that his family suffer less. Storch et al.9 found that children with ASD were more likely to have suicidal ideation or behaviour and children with AS were less likely, and that depression and trauma might play a significant role. The study sample showed that females (17.4%) were more likely than males (8.9%) to have suicidal thoughts and behaviour.9

Evidence indicates that intact executive functioning might be important for the ability of planning and committing suicide, as it is linked with better problem-solving skills.10 Robinson et al.11 state that children with ASD have a characteristic impairment in executive functioning, which might be related with intellectual planning ability. According to Hannon et al. 6 high-functioning individuals with autism are more likely to form suicidal behaviour. Hannon et al.6 claim limited research in suicidal behaviour in young people with ASD and existent research is based on small sample sizes, which might make conclusions unreliable. Mukaddes & Fateh7 conducted a mixed gender study in Turkey with32 males and 5 females and suicidal behaviour was only manifest in adolescents, age 15- 20 and not in children. Six individuals had associated suicidal behaviour but the majority were females. All three female adolescents had suicidal behaviour and two who did not, were children (Age 6). Out of 32 males, only 3 had suicidal behaviour (9.4%). Comparing the data to male adolescents, 27.3% had suicidal behaviour, less than half of the female sample.

Raja et al.12 researched suicidal behaviour in 26 psychiatric patients (16 AS and 5 ASD) and 5 with Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDDs-NOS). Suicidal ideation or suicide attempts were found in 7 with AS (6 male: Age 19-36 and 1 female: Age 19) and 1 committed suicide by disembowelment (Age 23).

Kocourkova et al.13 viewed suicidal behaviour in AS in two case studies with two boys aged 16. In the first case, a boy who believes in God wants to kill himself because of ‘unhappy love’ and disappointment in a girl who chooses somebody else and becomes ‘ordinary’ in the boy’s eyes. In the second case, a boy with speech impediment (dyslalia) does not believe in God and so suicide for him might become meaningless. The boy was self-harming when unsuccessful at school, even though achieving excellent results, but he had very few friends.

Cassidy et al.3 state depression is a high risk factor and 90% of individuals committing suicide have depressive symptoms. The study involved 256 men and 118 women), 243 (66%) stated suicidal ideation and 127 (35%) stated plans or attempts of suicide and 116 (31%) stated having depression. The suicidal ideation in women was slightly higher in total to men (71% female to 64% male) and suicide plans or attempts were also slightly higher in women (42%) than men (32%).

Jean-Paul Sartre14 mentioned that when we are confronted with an overwhelming scenario where there seems no exit, or we are consumed by the occurrence that we cannot physically move, we might create an alternate situation. This altered mental state, what Sartre called the ‘magical world’ substitutes the physical world in that specific moment to make it bearable. Individuals with ASD and AS are faced with overwhelming social situations, which result in a ‘no exit’ scenario. Suicide is the last resort, usually when all options are exhausted, perceived or real. Similar to Sartre’s example, there is no real or perceived physical escape route for sufferers, as the situation is deemed impassable, which might lead to physical destruction. Sartre’s play ‘No Exit’ claims: ‘hell is other people’, which might translate to individuals who are exposed to social scenarios they cannot understand and fully participate in.15 Others might have expectations which individuals cannot fulfil and vice versa due to social barriers and limitations caused by the disorder/problem. Individuals might perceive peers as threats to their own well-being. Even though naturally craving socialisation they tend to isolate themselves. In extreme cases this might be seen as an exit to escape the perceived ‘hell’.

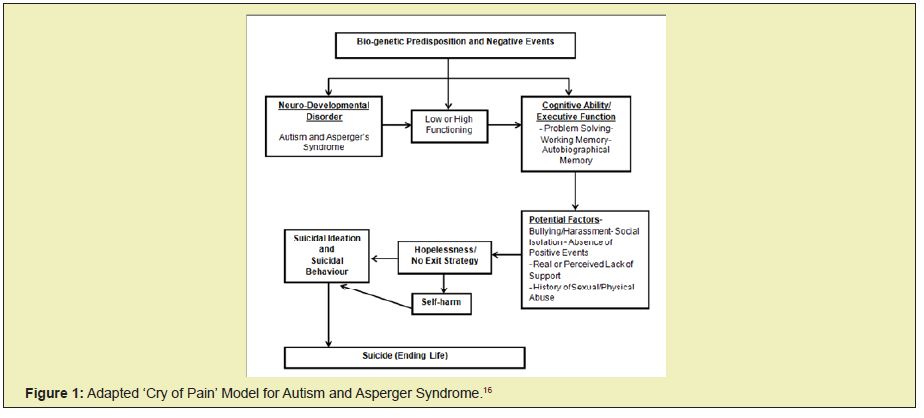

The adapted ‘Cry of Pain’ model below takes into account biopsychosocial factors.16 Bio-genetic predisposition paired with negative events appears to increase suicidal ideation/behaviour. Individuals with low spectrum autism are less likely to perform suicidal acts, whereas individuals with Asperger’s are perceived to be high-functioning. As discussed, to plan and execute a specific action, one requires a set of stages, such as higher planning and problem solving ability.

An intact working and autobiographical memory is an important part in the execution of any act but appears crucial in suicidal behaviour. It might be the case that individuals are recollecting negative episodes from their past, such as bullying/sexual abuse, which is so overwhelming to be overcome. People with AS feel socially isolated because they find it difficult to adjust to certain social scenarios. They appear to crave for social activities with others but are not able to perform fully at a social level, and might become vulnerable to bullying/harassment, which might lead to hopelessness and suicidal behaviour (Figure 1).

People with AS and ASD relate to individuals surrounding them, especially their careers. A professional yet empathic approach is essential to comfort an otherwise distressed and isolated individual. A person-centred approach is greatly appreciated and perceived by people with AS and ASD, which can be observed in verbal and non-verbal interaction. The person has to feel at ease and requires a safe support system, which can be fulfilled by the clinical staff and their personal support worker. Carl Rogers’17 core conditions (empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard) lead to a more positive well-being. There is a great bond between caretaker and caregiver, as it was acknowledged by a person with AS and a history of suicidal ideation/behaviour and self-harm (Age: 34) stating: ‘We usually mirror ourselves in our caregiver’. Individuals with AS and history of suicidal behaviour stated that they feel comfort in knowing that ‘high-functioning’ or ‘neurotypical’ people are in similar situations in their lives to themselves. It was noticed that young adults with AS tend to have an urge to be in relationships, which could be supported. Cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) evidently supports individuals to change their thinking styles and harmful/ dys functional behaviour. Carers and clinical staff are an important factor regarding decreasing the suicidal ideation, especially where people with ASD or AS in residential settings have no other immediate social support.

Anecdotally, Shuttleworth18 claims that individuals with AS can engage and would benefit from long-lasting psychotherapy sessions, rather than shorter interventions. A 10 year old child who had social difficulties and outbursts in the face of over-friendliness learned after many sessions (just before 13th birthday) to express and adapt himself more effectively to certain social situations.

Wasserman & Durke19 suggest that complex support systems are essential to ensure continuity of care for sufferers involving the family to decrease relapse of suicidal behaviour. As research into the efficacy of prevention and treatment methods is limited, it is difficult to predict positive outcomes. Psychotherapies such as CBT and mindfulness are useful. Support workers play a crucial role in individuals with AS and ASD as they are taking part in their daily life in residential settings and become almost substitutes for family members. Patients with suicidal behaviour generally relate or even identify themselves to people who are close to them as described in the previous example. Clinical sessions can be a good way of giving service users the essential comfort and social support they urgently require. A male client (Age 33) with AS and a history of self-harm and suicidal behaviour, indicated a sense of relief seeing other individuals having similar issues and that carers and clinical staff can become role models. The precursors for social isolation might be found at an early age at school where individuals are exposed to possible bullying due to lacking social cues. Family members should be integrated in treatments, as they usually know the persons’ life history best and can support professionals to overcome the burden of hopelessness and instil hope- the key to resolution of suicidal behaviour.20

Planning and executing specific actions requires a set of stages, which require greater planning and problem solving abilities. An intact working and autobiographical memory appears important in the execution of suicidal behaviour. Individuals might recollect negative past episodes, such as bullying/sexual abuse. Individuals particularly with AS crave social activities, but are not able to perform at a social level like others and feel frustrated and isolated. They cannot understand all essential and varied social clues to successfully take part. The absence of positive events and the prospect of unremitting negative future events appear to be the last phase of the dangerous cycle, potentially leading to suicidal behaviour. A person at this stage requires intervention in form of exit strategies, such as social support, to overcome the hopelessness. Self-harm can be an indicator of suicidal behaviour but it has to be viewed in conjunction with all other factors.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. O’Connor CR, Platt S, Gordon J (Eds.). International handbook of suicide prevention: Research, policy and practice. Oxford: Wiley– Blackwell. 2011.

- 2. Raja M. Suicide risk in adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(2):99–101.

- 3. Cassidy S, Bradley P, Robinson J, et al. Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: a clinical cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(2):142–147.

- 4. Brüne M, Schöbel A, Karau R, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of suicide in psychosis: the possible role of von Economo neurons.PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20936.

- 5. Balfe M, Tantam D. A descriptive social and health profile of a community sample of adults and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. BMC Research Notes. 2010;3(300):1–7.

- 6. Hannon G, Taylor EP. Suicidal behaviour in adolescents and young adults with ASD: findings from a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):1197–204.

- 7. Mukaddes NM, Fateh R. High rates of psychiatric co– morbidity in individuals with Asperger’s disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(2 Pt 2):486–492.

- 8. Abadie P, Balan B, Chretien M, et al. Suicidality in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (translated). Neuropsychiatrie de l’enfanceet de l’adolescence. 2013;409–414.

- 9. Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, et al. The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(10):2450–2459.

- 10. Burton CZ, Vella L, Weller JA, et al. Differential effects of executive functioning on suicide attempts. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(2):173–179.

- 11. Robinson S, Goddard L, Dritschel B, et al. Executive functions in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Cogn. 2009;71(3):362–368.

- 12. Raja M, Azzoni A, Frustaci A. AUTISM Spectrum Disorders and Suicidality. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2011;7:97–105.

- 13. Kocourkova J, Dudova I, Koutek J. Asperger syndrome related suicidal behavior: two case studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1815–1819.

- 14. Sartre JP. Sketch for a theory of the emotions. London: Routledge; 2001.

- 15. Sartre JP. No exit and three other plays. New York: Vintage Books; 1989.

- 16. Williams JMG. Cry of pain. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1997.

- 17. Rogers RC.Client– centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. London: Constable; 1951.

- 18. Shuttleworth J. The suffering of Asperger children and the challenge they present to psychoanalytic thinking, Journal of Child Psychotherapy. 1999;25(2):239–265.

- 19. Wasserman D, Durkee T. Strategies in suicide prevention. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors, The Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention–A global perspective. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 381–386.

- 20. Wing Series of Lectures. Research autism conference, Autism and challenging behaviour: One person at a time. 12th November, Copthorne Hotel, Newcastle